1 Jun 2011

There is a tendency for practices to buy the latest kit before truly assessing its cost effectiveness. Financial planning reduces waste by costing in factors such as staff training, maintenance and depreciation before you splash the cash.

“Vets are increasingly confident in using a range of machines in their diagnostic process.”

Many different pieces of equipment can benefit the modern veterinary clinic. However, there is a tendency to accumulate “toys” in the practice. They can end up gathering dust in a corner, only used every three months or when a member of veterinary staff decides to go on a CPD course.

Vets are increasingly confident in using a range of machines in their diagnostic process. So much so that it is clearly evident that thermometers and stethoscopes are now inherently less valuable than ultrasound and blood analysis equipment in diagnosing a heart condition or an infection.

In an ever-increasingly competitive market new equipment is needed, but its purchase can not always be justified in difficult financial conditions.

Many clinics open with basic materials (a stethoscope, thermometer and a fridge), and other equipment is added as required. But before we embark on purchasing the latest kit, it is important to remember that most preventive care does not require it.

Another common mistake when purchasing new clinical equipment is to ignore the imperative to acquire the knowledge required to use it to its full potential. Alternatively, when just one vet knows how to use a machine, others in the practice do not consider its use. Are we getting real value from this equipment?

Added to these factors we often forget to create plans to amortise our equipment. For example, for an ECG you could offer a trace at a reduced price to the owners of senior patients when they come for their yearly check. This is a win-win situation, as the equipment is amortised and the team accumulates experience by using it on non-urgent cases, establishing a baseline knowledge of common variables.

It is essential to perform a serious financial study prior to buying any new equipment. In doing so we should consider the following parameters:

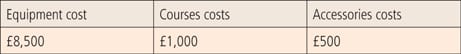

Let’s use a hypothetical piece of diagnostic equipment, valued at £8,500, to help understand what we should consider before a new acquisition. Buying cost must be added to the cost of training courses for its use, as well as any accessories (such as special forceps needed for a rigid endoscope).

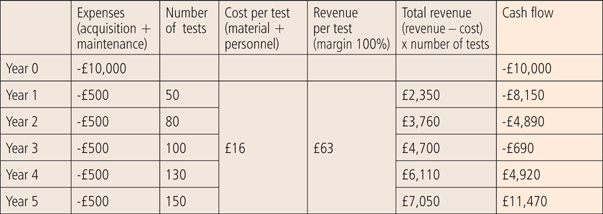

As we can see from Table 1, the real cost of the equipment is not £8,500 but £10,000.

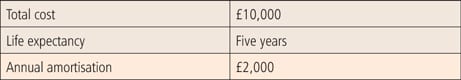

This machine has a life expectancy before it becomes obsolete. Many practices lose competitiveness due to overextending the lifespan of their machines. In this particular case, we will use a life span of five years (Table 2). The machine now costs £2,000 per year, but is this the minimum revenue to justify the initial purchase?

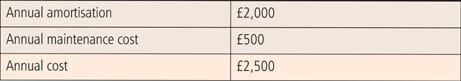

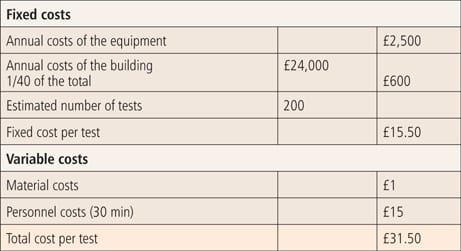

On top of yearly amortisation costs, there are maintenance costs – the annual inspection and maintenance of the radiography machine. The sum of amortisation and maintenance gives us the yearly running costs (Table 3). This is what the new machine will cost the clinic every year.

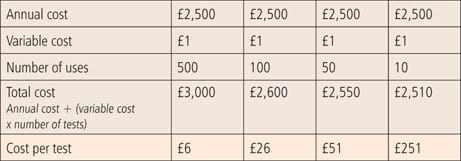

Now we must consider variable costs. For this, we estimate how many times we are going to use the machine every year, as well as the cost of every use (electricity and gel if we acquire an ultrasound machine, for example). It is quite clear from Table 4 that the more we use the equipment, the cheaper each usage will be.

Once we have decided the costs, we can calculate the investment return time. First of all, we need to decide the fee that we are going to charge for each test. There is a temptation not to pass the fixed costs of the practice on to the equipment, to keep prices down. While that is a good idea in the short term, you lose competitiveness in the long run as you will not be able to afford updates to the equipment.

How are we to decide the fee (Table 5)? Logically, the number of tests has to be a realistic estimation of the equipment’s use. This calculation can be done for equipment or fees for services provided at the clinic to establish profitability – whether we should increase its use, or get rid of it altogether.

If we charge £20 per day for hospitalising a pet and it costs us £25, each time we admit an animal we lose money. If each time we use the endoscope it costs £100 because it is used infrequently and we charge £50, is it not a better idea to sell the machine and refer those few consults to a more specialised practice?

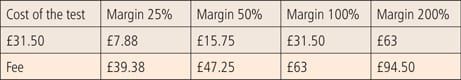

Now we are in a position to decide the fee for making a reasonable profit (Table 6).

If we want to achieve 200 tests it is reasonable to use a margin of between 50 to 100%. Besides, in the first year it is unlikely to achieve the expected number of tests and this rise will happen progressively. For an example, see Table 7.

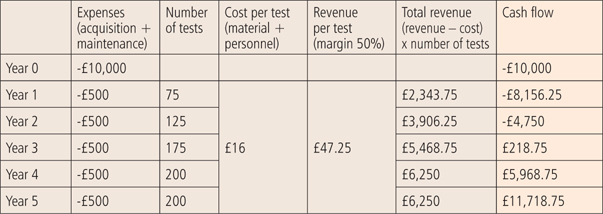

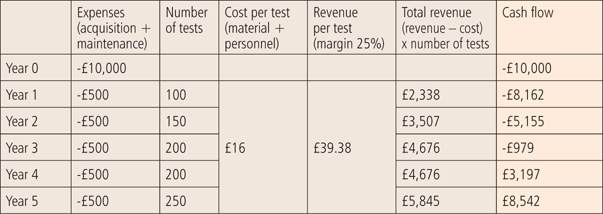

As you can see, at some point at the end of the second year, the new equipment starts to produce benefits for the clinic. Now we can decide to decrease the margin and hope that this will increase the number of tests. As we see from Table 8, it takes longer to recover the investment and the cash flow is lower at the end of the fifth year, despite performing more tests than expected in the final year. If we decide on a higher margin, it is safe to estimate that we will perform fewer tests.

In the third example (Table 9) the cash flow at the end is quite similar to that in example one, without performing the expected 200 tests (remember, this has its influence on fixed costs as well). However, the return of investment will not happen until the fourth year. This delay needs to be considered if we plan to get a loan to pay for the new equipment.

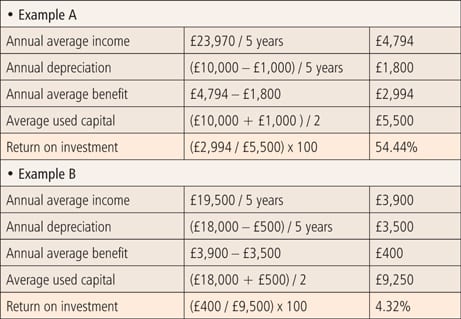

This method is simple and can easily be applied to any clinic. If a machine does not pay for its own cost during its life span, we should not buy it as it will be a burden. Now that we can calculate the time it takes to recover the investment, we can determine the concept of return on investment (ROI).

This is expressed as a percentage that allows us to compare different pieces of equipment and decide which one to buy. The first requirement is to find out the residual value of the equipment after the period that we plan to use it. In our example, we use a residual value of £1,000 (Table 10, example A).

The method to calculate ROI for the equipment in example one is:

This method is a simplification as it was done for amortisation and has not taken into consideration depreciation of the currency. It is quite clear that with a return on investment of 54%, it is logical to acquire this piece of equipment. However, there would be occasions when this value could be lower. Look at another example (Table 10, example B):

In this case, the equipment value is £18,000 and the residual value is £500. In five years it produces £19,500. The return on investment is just 4.32%. There are financial investment products with better profitability and are a lower risk, so it might be an option to consider them and wait for better times.

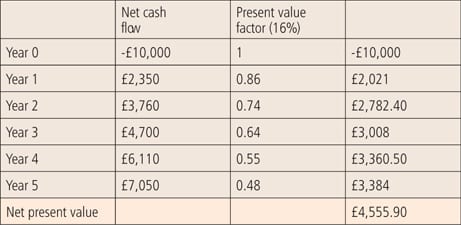

In both models, the money has the same value in year number five and in year one. Everyone knows this is not strictly true, as money devalues with time. To correct this, we use something known as net present value (NPV).

The NPV corrects for the fact that £100 today will not have the same buying power in five years (not even next year). Any government bond, for example, would give you an ROI of around 6% and practically no risk (except for whoever bought Greek bonds). Acquiring new equipment has a higher risk, as no one is sure that clients will demand its service or even that a new machine would not become obsolete before its lifespan is over. Therefore, a risk factor is added to take account of this. If an average bond gives you an ROI of 6%, for any veterinary equipment we should make it 16% (a risk factor of 10%). Let us see how the net cash flow changes in our first example in Table 11.

The benefit amount is still considerable, but the ROI is reduced significantly. You should always calculate the NPV, as an investment that looks potentially positive can turn out negative after applying a risk factor to consider currency depreciation. It is also very useful to effectively compare the acquisition of different machines – choosing between different offers for the same machine that might have different maintenance costs and residual values.

For example, what is the best acquisition – an ultrasound machine or a digital developer for the x-ray machine? We should also bear in mind that if we acquire an ultrasound machine, this affects the number of x-rays that we take. If we are going to spend thousands of pounds, it is natural to spend a few minutes calculating if it is worth buying. Once we have decided that we are going to invest, we should consider the different options to finance that purchase.

The clinic’s equipment can be bought with cash, credit or by leasing. If the clinic has enough cash to spare, it is a great temptation to buy in this way (especially if we listen to the seller and the amazing discount he offers us if we pay cash, to avoid paying any interest), but we have to consider if the money can produce more income from another investment or be kept for possible emergencies.

Credit allows you to use the equipment before it is fully paid, but the price increases due to interest. We can get a loan from the bank if the interest rate is better than the one offered by the salesman. Contact your accountant to find out which is the best option from a tax point of view.

By leasing you pay for the equipment gradually and this allows you to reduce tax on the payments. The contract can have a defined time period or be unlimited. If it is over a defined period, there is a possibility of acquiring the equipment for a previously agreed residual value.

Ultimately, before acquiring any new equipment, think carefully about amortisation. Think about creating tools for the equipment to be used at the expected volume and then consider all the different options for payment.