1 Oct 2019

People are built to worry about the future, skilled professionals especially. In this article, futurists and innovation consultants Greg Dickens and Guen Bradbury outline some possible futures for the veterinary profession, and suggest ways to be ready to get the most out of it...

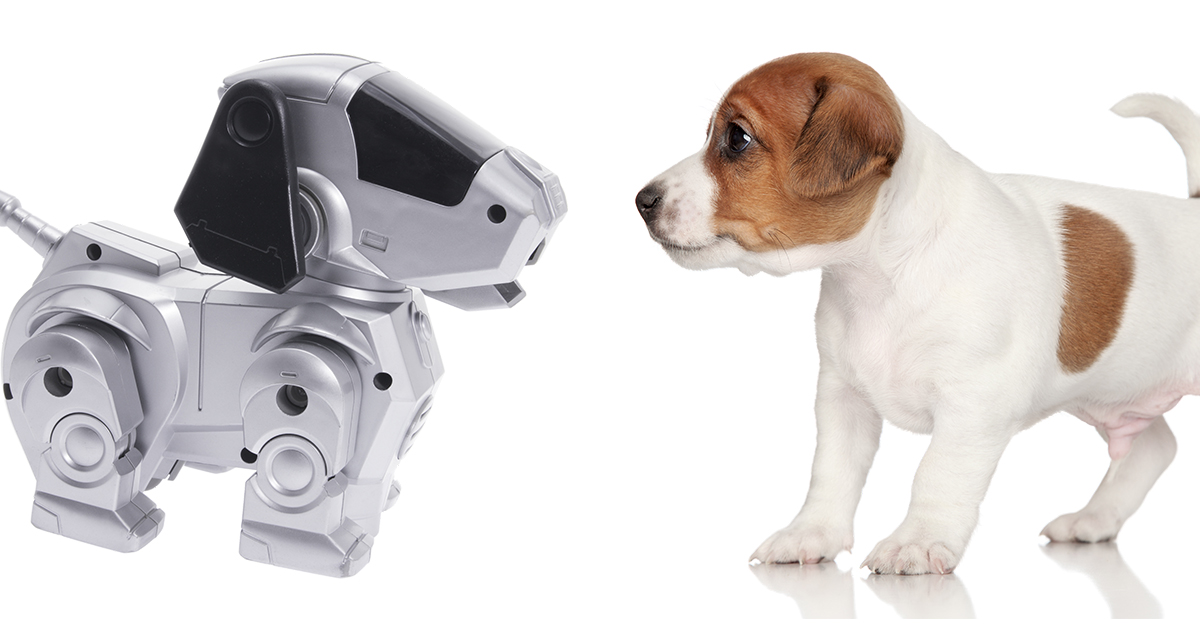

Image © Silkstock and jagodka / Adobe Stock

If Dr Emmett Brown taught us anything (other than how to properly accessorise a lab coat), it’s that the future is what we make it.

For vets in the UK, making our future has always meant streamlining practices and integrating new technology. And, despite our trepidation, the profession has made huge leaps forward. Each time, we overcame our fears and reservations, and reasoned that the risk was worth taking for the tantalising promise of a better future for patient, client or vet.

So what huge leaps do we still have room to make? What advantages might our three stakeholders find just around the corner? One way to narrow down the possibilities, to sort the pipe-line from the pipe-dream, is to follow the laws of physics. And those laws of physics offer a huge amount of leeway when imagining what sorts of advances are possible.

It’s not against the laws of physics, for example, to suggest that in some gleaming JJ Abrams future, a vet might step into their office first thing in the morning to a case like this:

Advantages to patient. Jennzy is, in turn: kept from bleeding to death; kept better protected from respiratory distress; given smaller skin wounds leading to less pain, faster healing, and lower chance of infection; sent home much faster; and left without the long-term morbidity risk of indwelling metalwork.

Advantages to client. Jennzy’s owners are given a one-stop-shop and the peace of mind of knowing their pet is being cared for as quickly and effectively as possible.

Advantages to vet. Our vets get the professional thrill of having the tools needed to see a case through from beginning to end. They get to save time gathering data, get answers to questions they didn’t even know that they wanted to ask before, and they get to save more lives, working on whatever surgical cases come their way.

All of this sounds great (and it is all very possible to achieve – the root technology of every tool mentioned, from the cannula that can detect flow rate, to the dissolving trauma plate, is already proven in the laboratory). So, why haven’t we all strapped on our rocket boots and boldly gone to that particular veterinary future?

Because the laws of physics aren’t the only gatekeepers. If we want to make a better veterinary future, we also have to get past a list of other laws that close off possibilities in sneaky, underhand ways.

Economics. Think back to Jennzy’s case. While the technology would have allowed any vet to handle this orthopaedic case, the vet would have needed the whole morning to do so. And arranging a business model that pays a GP vet sufficiently to see no other first-opinion cases in a morning would be complex. Similarly, this ultra-high-tech case management relied on multiple small uses of high-capital cost equipment. Without a high load of such cases, the pay-back times become impossible to justify.

Logistics. Those technologies also all require a significant amount of distribution or logistics. Many have consumables with a short shelf-life, and others take a huge amount of space. And, as with all logistics, things spiral – have you got a frozen blood sachet for every patient? You’ll need a huge freeze and a huge back-up generator, but have you got a huge freezer and a back up generator? You’ll need a huge fuel tank, and so on.

Regulation. The future described had: automated diagnosis and treatment planning (the oxygen); home-made implanted devices (the polymer plates); and data from a third party used without explicit consent (the crash footage). All of these are of questionable legality nowadays, and people shy away from uncertainty where regulation is concerned.

Psychology. Game theory scholars among us will already have spotted that any vet in this future, apart from those with all of these tools, is at risk of losing out. Threatened by having their training apparently devalued by this assistive technology, many other vets will, consciously or subconsciously, move to discredit or disallow it.

So, let’s consider all of these rules over a time horizon of, say, 10 years. That’s close enough to understand people’s challenges and motivations, but far enough out to show us some difference. We can say that it’s not unreasonable that a vet in 2029 might step into his or her office first thing in the morning to a case like this:

Once again, all the technologies mentioned in it exist. This time they aren’t lab level, they’re all on the market, in some form or other. You’ll notice that the advantages here are more subtle – our vet of 2029 is still working in 10 to 15 minute consults; they still need to collect data and draw blood; one person’s surgical repertoire is still limited; and there are no infallible AIs running everything.

Advantages to patient. Niffler benefits from significantly decreased stress and increased speed, both in the short term (namely, short, mostly hands-off examination, and low-stress blood draw), and in the longer term (that is, his course of transdermal medication, and the single-visit diagnosis).

Advantages to client. Niffler’s owner only needs one short visit to the vet and doesn’t need to wait for test results. The practice group’s subscription service allows frank and open discussion of the price of options.

Advantages to vet. Things are faster, things are easier, things are cheaper. However, there are also logistical benefits: the practice only needs one testing lab, despite its many branch surgeries; data from home and from the practice’s instruments is automatically recorded; subscription business models lead to many fewer unpaid bills and a more dependable income.

Maybe, compared to the white floors and holograms of the “Laws of Physics Scenario”, these advantages sound inconsequential. But adding just these benefits together creates a world where vets can provide better care for animals. A world in which we’re less stressed and rushed, and better paid and appreciated – achieving at least three of the six ambitions the profession fed into the Vet Futures investigation run by the RCVS and BVA.

So, how can practices get ready to make their future as new ideas and technologies come along? Innovation consultants and futurists spout a lot of general platitudes, such as “stay hungry” and “follow the customer”, but here are three more concrete recommendations that might help vets:

Get a great internet connection. A lot of the future is going to be data driven, and accessed at point of care. If your practice wifi is slow or unreliable, you’re going to be left out. Get it fixed, pronto.

Ask for beta testers. A total of 90% of your clients want a traditional approach to animal medicine. That means 10% will, if you ask them, accept a degree of risk in exchange for being at the cutting edge of the veterinary industry. Beta testers are invaluable, so be open and honest: What are you testing? What are they risking? Why should they join in?

Be ready to pool resources – nearby practices are not your mortal enemy. Being open and ready (you have made contact and had the discussions) to pool resources (for example, money, space or time) allows both practices to access futures that would be closed to them otherwise. You can still compete, just compete at a higher level.

Others include “make friends with the VDS”, “understand before you invest”, “hire a tech-y vet or nurse”, and “don’t underestimate the flexibility of the British public”, but you can figure those out for yourselves.

A lot of figuring out will be required – more than ever before in our industry’s history – and risks are involved. But the potential benefits to animal health, to the client, and to us as professionals are enormous. Good luck out there, and remember: the future’s what we make it.