1 Sept 2023

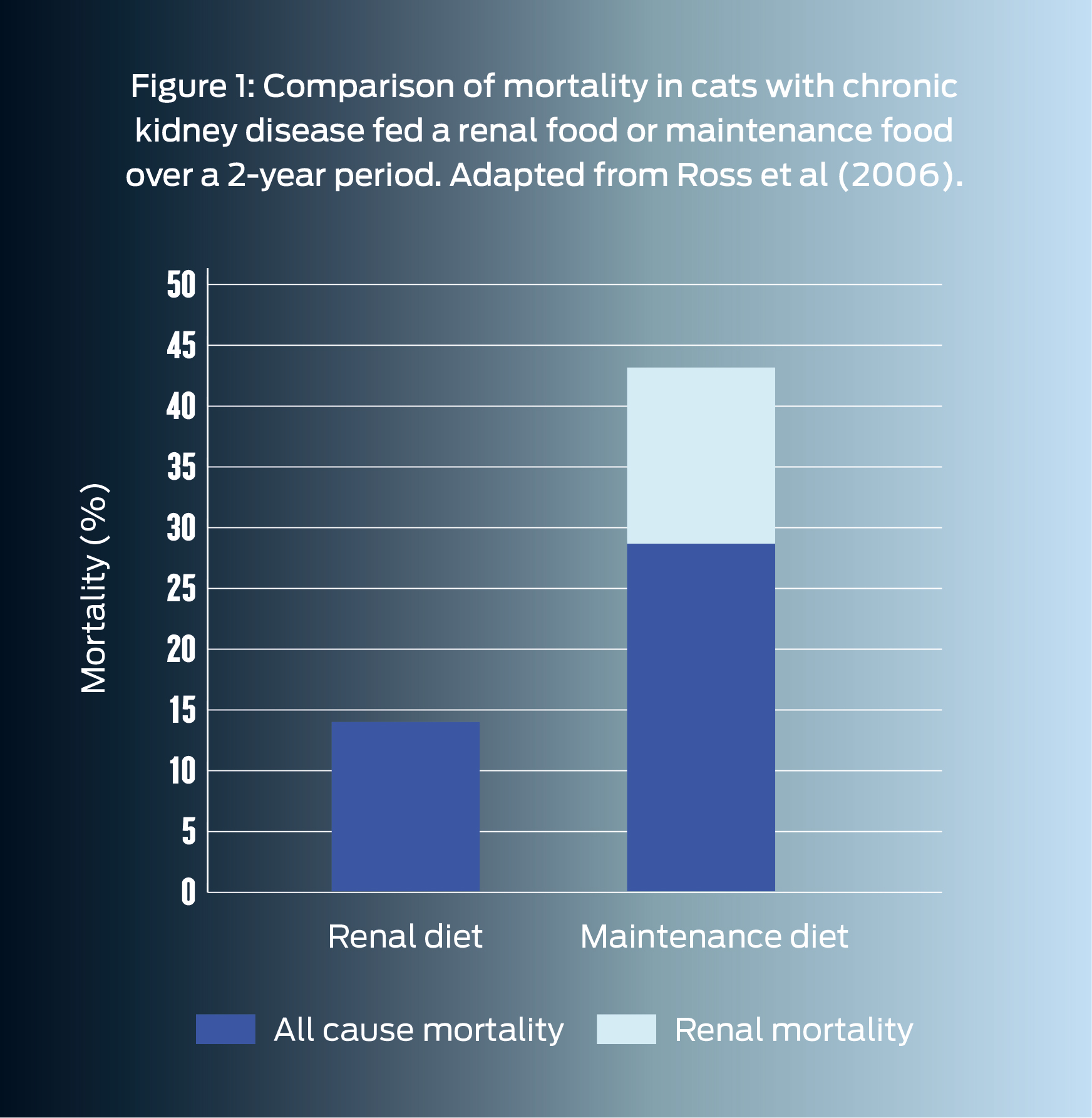

Numerous studies have demonstrated clear benefits in using renal diets to manage cats with International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) Stage 2 CKD onwards – read more here.

Image © Neira/Adobe Stock

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a highly prevalent disease estimated to affect 30% of cats over the age of 121.

Risk factors and causes associated with the development of CKD are currently not well elucidated, and most cases are classified as idiopathic in origin. However, what we do know is that appropriate dietary management of this condition is important in order to slow down disease progression and increase longevity in feline patients2.

Dietary intervention is the cornerstone of CKD management, and numerous studies have demonstrated clear benefits in using renal diets to manage cats with International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) Stage 2 CKD onwards3.

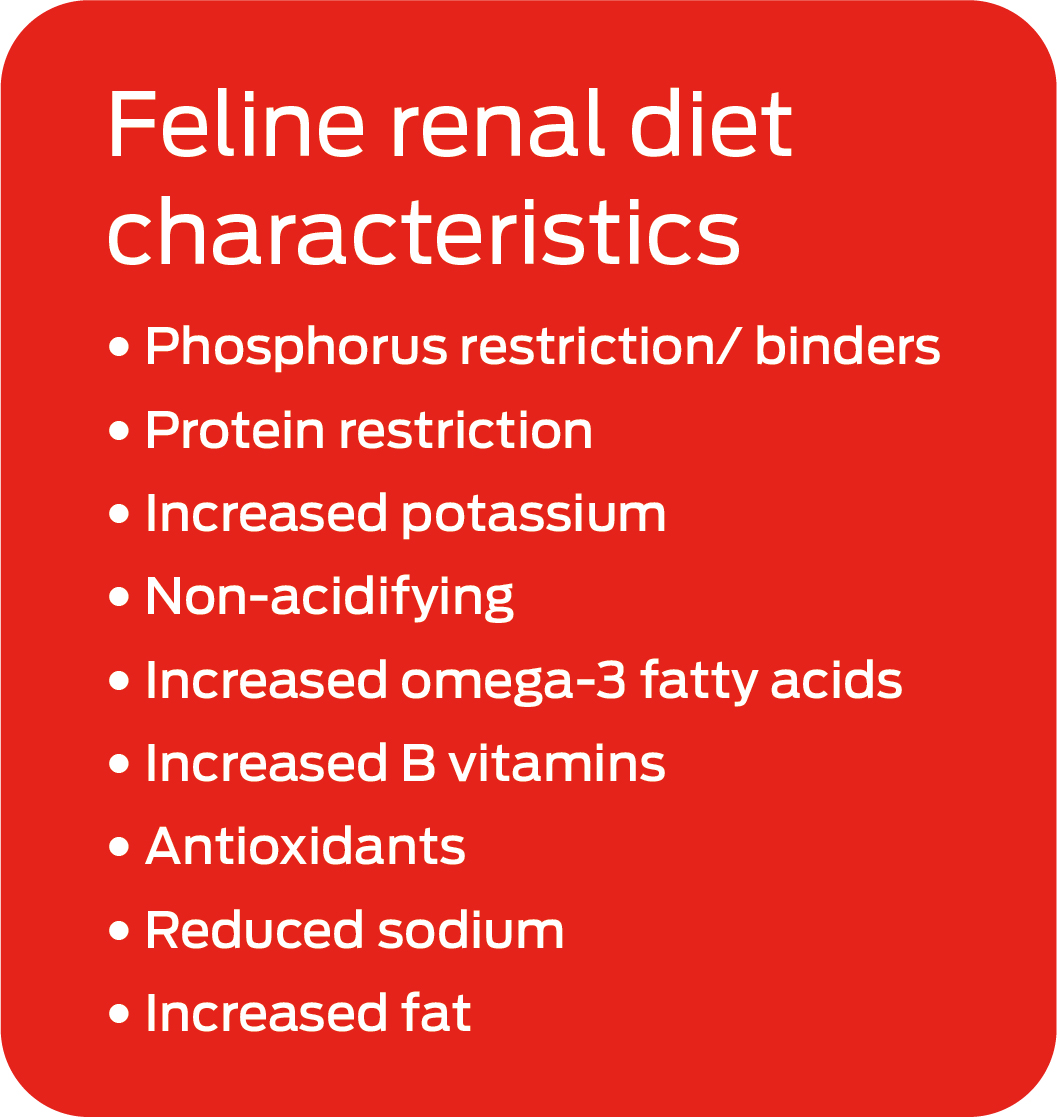

There are currently a number of different renal diets that are commercially available in the UK, all with relatively similar nutrient adaptations that can help to slow the progression of kidney disease, prolong survival time and maximise quality of life.

Phosphate restriction is thought to be the most important influencer of survival in cats with CKD4. Restricting phosphate slows the progression of chronic kidney disease by reducing morphological damage to the kidneys.

Phosphorus restriction also helps to reduce plasma parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels, minimising the risk of secondary renal hyperparathyroidism – a condition which, unless treated, will progressively worsen, and is associated with reduced survival times5. High levels of parathyroid hormone may contribute to the uraemic state by acting as a uraemic toxin. Increased parathyroid concentrations can also contribute to renal damage as this can result in increased calcium influx into renal tubular cells and precipitation of calcium phosphate in the lumen of the renal tubules.

The current advice is that dietary phosphate should be restricted when the renal patient has confirmed CKD, and IRIS provides therapeutic serum phosphate targets for each CKD stage.

As CKD progresses, serum phosphate tends to increase and may become refractory to control with dietary phosphate restriction alone, rising above IRIS’s therapeutic targets for blood phosphate levels. In these cases, phosphate binders may also need to be added to the renal diet to control serum phosphate levels. Phosphate binders themselves can reduce food palatability though so ensuring adequate intake once such binders are added is important, and in some cases more than one phosphate binder may need to be trialled before there is adequate acceptance

Protein is not thought to be a key influencer of survival time per se but has an important impact on quality of life. Restricting protein can help to minimise the levels of nitrogenous waste, as well as the formation of uraemic toxins, which can contribute to nausea and inappetance. Reducing dietary protein may also help to reduce proteinuria. Proteinuria is less common in cats with CKD compared to dogs, but, where present, elevated urine protein:creatinine (UPC) in feline CKD patients has been demonstrated to be a negative prognostic factor7. Quality, as well as the level of protein, is important, and proteins fed should have a good amino acid profile and high bioavailability.

Protein levels and the amount of protein restriction vary between different commercially available renal diets, and there is controversy about the degree of protein restriction required. Whilst protein restriction in the later stages of CKD is helpful to minimise uraemic toxin production, protein plays a key role in supporting lean body mass and body weight – known to be important factors correlating with survival in both healthy cats and cats with CKD8,9 – and there is still no consensus on the optimal dietary protein levels for cats at different stages of CKD or when protein should start to be reduced in the diet.

Increasing dietary potassium aims to compensate for potential excessive loss of urinary potassium in CKD and helps to reduce – although not completely remove – the risk of hypokalaemia, which can contribute to ongoing renal damage in addition to inappetence and lethargy.

Acidosis is common in renal disease, and can cause anorexia, lethargy, weight loss, and increased protein breakdown. Renal diets are generally designed to be alkalinising to help increase bicarbonate levels and neutralise any acidosis.

Increased essential fatty acids, particularly EPA and DHA, may help reduce glomerular hypertension and minimise glomerular inflammation. Renal diets with higher omega-3 fatty acid levels may be associated with a longer survival time, although a causal relationship has not been established.

Increasing B vitamins can help to compensate for the loss of water-soluble B vitamins in diuresis which can otherwise contribute to deficiencies with resultant inappetence and other clinical signs.

Antioxidants can reduce oxidative damage to the kidneys, which is exacerbated in CKD. However, whether antioxidants within renal diets have a clear renoprotective effect in kidney disease is still to be determined.

Moderate sodium reduction may help control blood pressure in cats with concurrent hypertension, although evidence for a beneficial effect in cats with chronic kidney disease is still lacking. Significant sodium restriction should be avoided, however, as it can stimulate the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system with resultant negative impacts to potentially increase renal fibrosis and accelerate progression of CKD.

Fat is the most energy dense nutrient, so increasing fat levels helps to increase energy density as well as support palatability. Appetite and maintenance of body condition score can be a challenge in cats with CKD but supporting adequate energy intake and minimising weight loss is crucial.

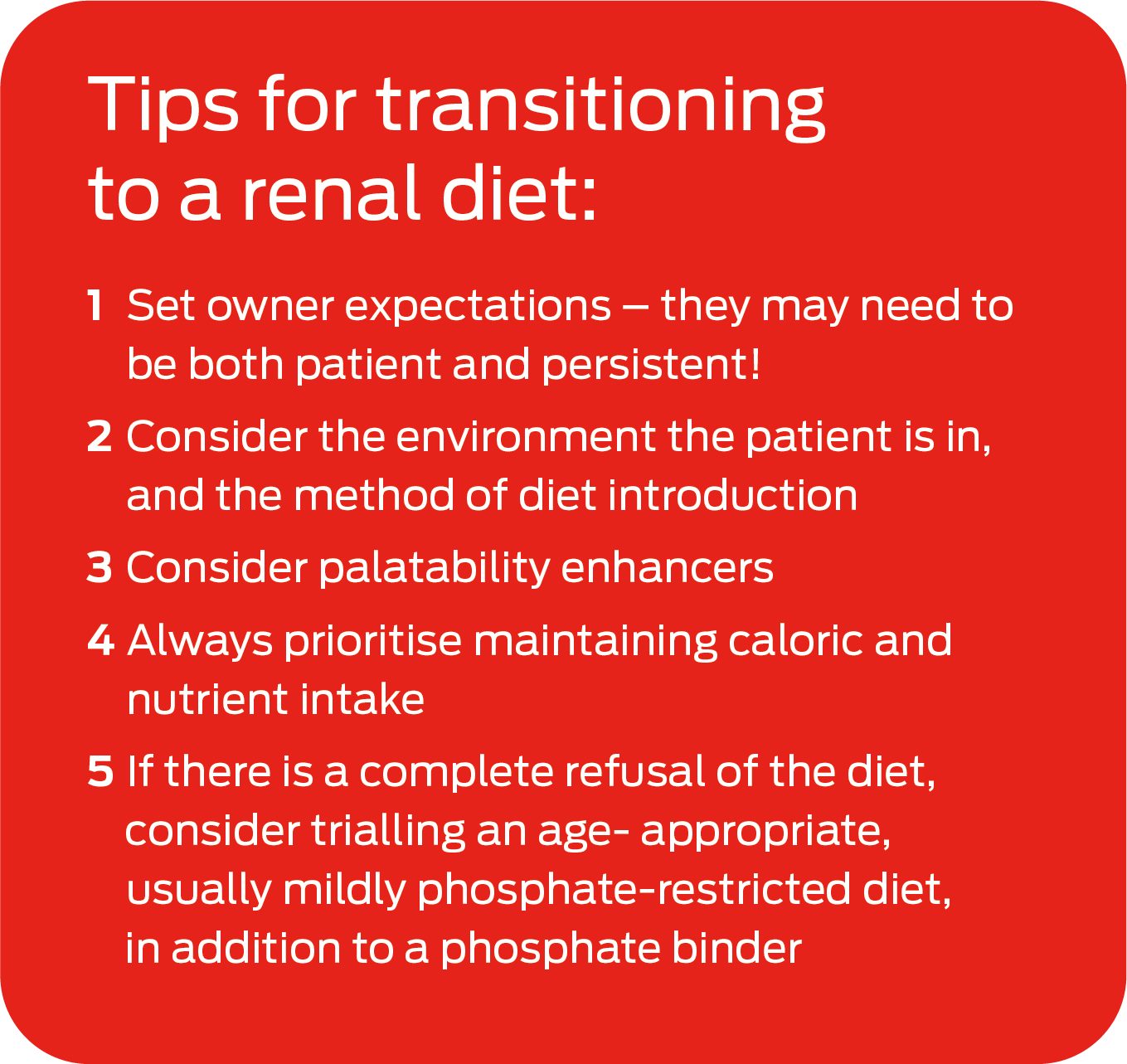

There can often be challenges with acceptance of any new diets in cats – particularly in renal patients. If there are any concerns that a cat is suffering from nausea this should be medically managed in advance of introducing a new diet and the cat should be home and settled before diet introduction. To maximise the likelihood of success, a renal diet most similar to that which the cat is currently on should be selected. Whilst selecting a wet renal diet may be preferable to maximise fluid intake and support hydration, if a cat has only ever eaten dry food it is sensible to select a dry diet. Owners can also consider trialling renal diets from different brands, as textures and flavours do differ.

Persistence with dietary transition is key: it can take a month or more for the feline patient to accept a new diet. Because of this, setting owner expectations prior to dietary transition is important, particularly as this is likely to increase their perseverance if diet acceptance is not rapid. The environment the cat is in and the method for introduction should also be considered. For example, owners could consider diet introduction in a new bowl (next to the bowl with the old food) as this tends to be preferred to mixing the old food with the new renal diet. Palatability enhancers may also be helpful in some cases.

Transition to a renal diet is possible in most patients, although maintaining caloric and nutrient intake is critical in these individuals and should always be prioritised.

If there is a complete refusal of all renal diets tried, the recommended approach would be an age-appropriate senior, mildly phosphate-restricted diet, with the addition of an intestinal phosphate binder. Although this will not provide the other advantageous elements that renal diets offer (listed above) it will help to reduce phosphorus intake, at least in the earlier stages of CKD. This approach also has challenges though, as many phosphate binders can be unpalatable and poorly accepted.

In summary, renal diets form a key component of CKD management. There are a number of feline renal commercial diets available with a number of nutritional modifications to slow disease progression and increase longevity in renal patients. A staged approach is recommended, since patients in the early and later stages of CKD have differing nutritional requirements – particularly with respect to protein requirements. Many renal diets now reflect this, with nutrient profiles formulated to better support either the ‘earlier’ or ‘later’ stages of CKD. These are offered in a range of flavours and textures to maximise the likelihood of acceptance. However, it is always important to also consider appropriate dietary transition methods in renal patients and the importance of maintaining nutrient and calorie intake in these individuals.