3 May 2022

Urolithiasis is commonly seen in dogs in general practice, but a large proportion of cases seen involve calcium oxalate or struvite stones.

This article follows the management of two more unusual cases seen in summer 2021. Byrti the Dorset old tyme bulldogge developed cystine uroliths, and has needed both surgical and medical treatment to manage his condition. Vince the Dalmatian has needed treatment for urate urolithiasis.

The likely causes behind their conditions are discussed, along with the treatment options available to manage them in the long term.

Haematuria and cystic calculi are a common presentation in practice, and the profession is familiar with the approach to treatment when the analysis of struvite or oxalate is confirmed by the lab. Recently, in their small animal practice, the author’s team encountered two more unusual cases of urolithiasis.

Byrti the Dorset olde tyme bulldogge and Vince the Dalmatian are both lovely patients, and have proven to be interesting and challenging cases to treat.

The author wanted to share her practice’s experiences in the diagnosis and treatment of these unusual cases with other small animal vets.

Overall prevalence of urolithiasis in dogs has been estimated to be between 0.25% to 1%1,2.

Within those overall figures, much variation exists in cases depending on their geographical location, gender, neuter status, breed and body size1-3.

Trends in urolithiasis also appear to shift through the years3.

The urolith centre at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities analyses samples for patients across six continents, giving them a great opportunity to look at patterns in urolithiasis3,4.

Looking at nearly 100,000 submissions from 2009-10 suggested that urolithiasis is most common in females around seven years of age3.

Calcium oxalate and struvite stones made up a large proportion of the samples (Table 1)3.

| Table 1. Urolith percentages (Minnesota Urolith Center, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities submissions, 2009-10)3 | |

|---|---|

| Urolith composition | Percentage of submissions (N=99,598) |

| Calcium oxalate | 45.2 |

| Struvite | 42.5 |

| Purine (including urate and xanthine) | 5.1 |

| Cystine | 1.2 |

| Calcium phosphate carbonate | 1 |

| Silica | 0.7 |

| Calcium phosphate | 0.5 |

| Other | 3.4 |

Seeing two young male dogs such as Byrti and Vince with urolithiasis was unusual within the general dog population, but on researching further, the author’s team realised the conditions they suffer from are not unexpected in their breeds1-8.

Byrti is a two-year-old, male, Dorset olde tyme bulldogge (Figure 1), presented to the author’s practice in June 2021 with haematuria and stranguria.

After his clinical signs failed to respond fully to a course of NSAID and antibiotics, Byrti was admitted for further investigation.

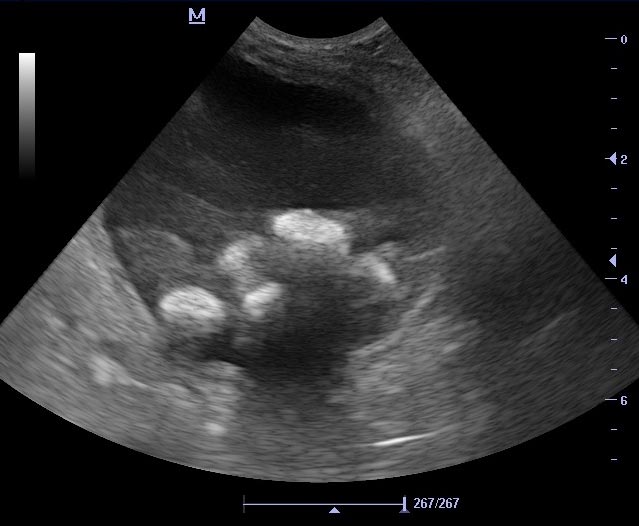

An ultrasound scan of his bladder revealed multiple small hyperechoic structures within the lumen of the bladder, creating acoustic shadows suggestive of cystoliths (Figure 2).

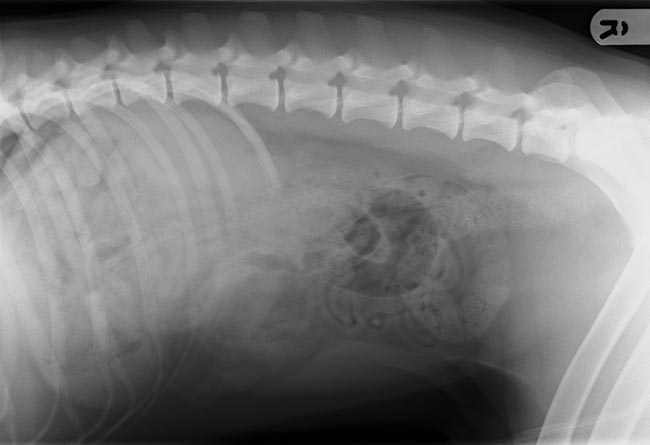

As Byrti was an entire male at this point, his prostate was examined on scan, and found to be uniform and of normal size. A lateral abdominal x-ray confirmed multiple small calculi within the bladder, but without the familiar radiopaque appearance of struvite or oxalate stones (Figure 3).

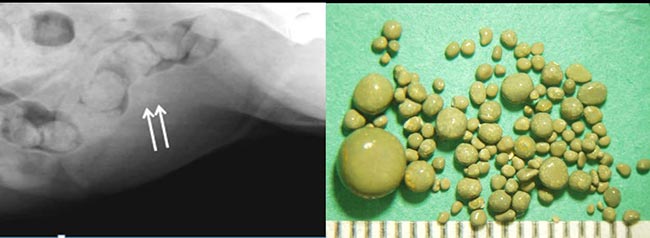

After removal of the calculi by cystotomy, they were confirmed as cystine uroliths (Figure 4).

On further reading, evidence became apparent that this type of urolith not only has specific requirements for dietary management, but also has several predisposing factors that need to be considered in treatment4-8.

In most dogs, several amino acids pass into glomerular filtrate in the nephron and are then reabsorbed in the renal tubules by the cystine, ornithine, lysine and arginine (COLA) transporter4,6-8. A proportion of dogs have an inherited defect in this transporter, leading to high concentrations of COLA in urine4,6-8.

Cystine has a low solubility in urine, leading to high risk of urolith formation in affected dogs4,6-8. Studies suggest that this is much more common in males2-7. Predisposed breeds include the Labrador retriever, Newfoundland, basset hound, dachshund and bulldog, but the condition has been seen in up to 170 breeds of dog1-8. Genetic tests are available to detect the condition in the Labrador retriever and Newfoundland4,7.

The amount of cystine in urine is highest in younger dogs and starts to decrease beyond five years of age4-7. This could explain why urolith formation is most common in young adult dogs of four to six years of age3,4,6,7. For some dogs with the condition, androgens appear to increase the degree of cystinuria4-8.

In treating cystinuria, the ongoing output of cystine into urine means that urolith removal is not likely to be curative. Studies also suggest that complete removal of cystine stones from the bladder is very difficult, even for experienced surgeons, with a proportion of stones left behind in 15% of cases4.

Dietary and medical management relies on reducing excretion of cystine into urine, and increasing solubility of any of that which remains (Panel 1)4-8.

Increasing cystine solubility in urine

Reducing cystinuria

The success of medical treatment can be monitored in many ways4,7,8:

The complex nature of cystinuria means the treatment approach needs to be adjusted for each patient4-8.

Following surgery, the author’s team started Byrti’s treatment plan (summary in Table 2). He was changed to Hill’s u/d diet, and urine pH and SG were monitored.

| Table 2. Summary of Byrti’s treatment | |

|---|---|

| Treatment | Details |

| Cystotomy | Initial management of urolithiasis and gave diagnosis of cystinuria |

| Hill’s u/d diet | Low protein, urine alkalinising diet |

| Potassium citrate supplement (75mg/kg twice daily) | Urinary alkaliniser to maintain urine pH consistently more than 7.5 |

| Deslorelin implant | To remove androgen influence and assess if this reduced cystinuria |

| Increased water intake | Needed to reduce urine specific gravity to less than 1.020 |

| Scrotal urethrostomy (and castration with scrotal ablation) | To reduce risk of repeat urethral obstruction (castration will reduce androgen-dependent cystinuria) |

| Phenoxybenzamine (0.5mg/kg twice daily) and dantrolene (1mg/kg twice daily; both off licence). | Urethral relaxants to manage urethral spasm post partial obstruction |

Having found that his urine pH was not consistently above 7.5, the author’s team also added potassium citrate supplement as a urinary alkaliniser.

Byrti’s u/d diet was only available in a dried form (though it is now also available in wet as well) and, even with his owners adding extra water to his diet, the author’s team has found the urine dilution goal difficult to achieve. To assess whether his condition was androgen dependent, the author’s team sent urine for cystine:creatinine assay before using a deslorelin implant as a temporary chemical castration. The level of cystinuria was assessed again later on post-castration.

Cystine levels in urine had not reduced after castration showing that, unfortunately, Byrti’s condition was not androgen linked (Panel 2).

Normal (one to five-year-old dogs: 0 to 179

Byrti pre-castration: 1,119

Byrti post-castration: 1,722

Despite medical management of his condition, Byrti had several further episodes of haematuria and showed evidence of some stones reforming in the bladder.

He went on to develop partial urethral obstruction, and was unable to void the urolith with the help of urethral relaxants phenoxybenzamine and dantrolene.

At this stage, surgical management was needed to relieve the obstruction and reduce risk of further obstruction.

Byrti underwent castration with scrotal ablation to allow a scrotal urethrostomy. The author’s team’s experiences with Byrti certainly highlighted the recurrent nature of this condition.

The author’s team hopes this surgery, along with continuing medical treatment and the benefits of castration, will allow Byrti to live comfortably with his condition.

If he continues with repeated episodes of urolithiasis, the next step in treatment would be to introduce a cystine binder, such as tiopronin.

This is available by prescription from human pharmacies for off-licence use, and has been found to have a beneficial role in the dissolution and prevention of uroliths in recurrent cases4,6-8.

Studies suggest this drug is generally well tolerated in long-term use, but a small proportion of dogs developed side effects6-8. The most notable adverse effects were mild proteinuria, aggression and myopathy, all of which stopped on cessation of the drug6-8.

Several other drug therapies are being looked at for the future, to help both humans and dogs with this condition, but currently they are only in the early stages of research7.

Vince is a two-year-old male, entire Dalmatian (Figure 6) presented with haematuria and dysuria in August 2021.

As he was showing significant difficulty in passing a stream of urine, the author’s team began investigations immediately.

A catheter was passed easily, suggesting no urethral obstruction, but bladder ultrasound revealed acoustic shadowing consistent with a large cystolith (Figure 2). This was shown to be radiolucent on plain abdominal radiography (Figure 7).

Removal of the urolith at cystotomy confirmed it to be of urate origin (Figure 8), prompting further research into the treatment options for Vince.

Purine metabolism in the body produces uric acid. This is usually removed from the bloodstream and metabolised by the liver into highly soluble allantoin4,8.

Some dogs – particularly the Dalmatian and bulldog – have a genetic mutation that leads to the failure of transportation of uric acid into the liver cells4,8.

As a result, high concentrations of poorly soluble uric acid are excreted in urine, leading to a risk of urolith formation4,8. The same problem can be seen in portosystemic shunts due to a failure of urate delivery to the hepatocytes4,8.

In the Dalmatian, the formation of uroliths is much more common in males, with females in one study only making up 3% of cases3-5,8.

Identifying the cause of the hyperuricosuria is important to deciding on a treatment plan. Patients with a portosystemic shunt will need treatment of this condition, so it is important to assess bile acid levels in dog breeds other than the Dalmatian or bulldog4,8.

As Vince was a Dalmatian, the author’s team’s research focused on methods to treat dogs with the genetically induced condition. Treatments are based around increasing the solubility of urate in the urine and reducing the excretion of uric acid (Panel 3)4,8.

Increasing urate solubility in urine

Decreasing uric acid excretion

Medical treatment can be successful for dissolving bladder stones – in some cases within four weeks8.

One study showed full medical dissolution in 40% of cases, reduction in urolith size in 30% of cases and no change on 30%8. For cases with severe signs or urethral obstruction, surgical treatment is needed.

Monitoring for success of dietary changes and for signs of recurrence is important4,8.

Vince had significant dysuria due to his cystolith, so a cystotomy was needed to quickly alleviate his clinical signs.

Although he was previously on a Dalmatian-specific diet, his urine pH at diagnosis was 6.

Postoperatively, the author’s team started him on Hill’s u/d, which has managed to maintain urine pH of more than 7 and SG of 1.010. He is not currently on allopurinol.

The author’s team will continue to monitor his urine and carry out periodic bladder ultrasound scans.

The author’s team look forward to seeing Byrti and Vince for their monitoring visits as they are real characters. Byrti always insists on watching the screen during his ultrasound scans.

The author’s team hopes both dogs continue to cope with their conditions and that sharing their cases may help manage other similar patients.