31 Oct 2022

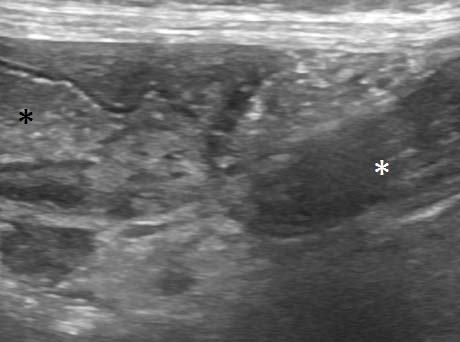

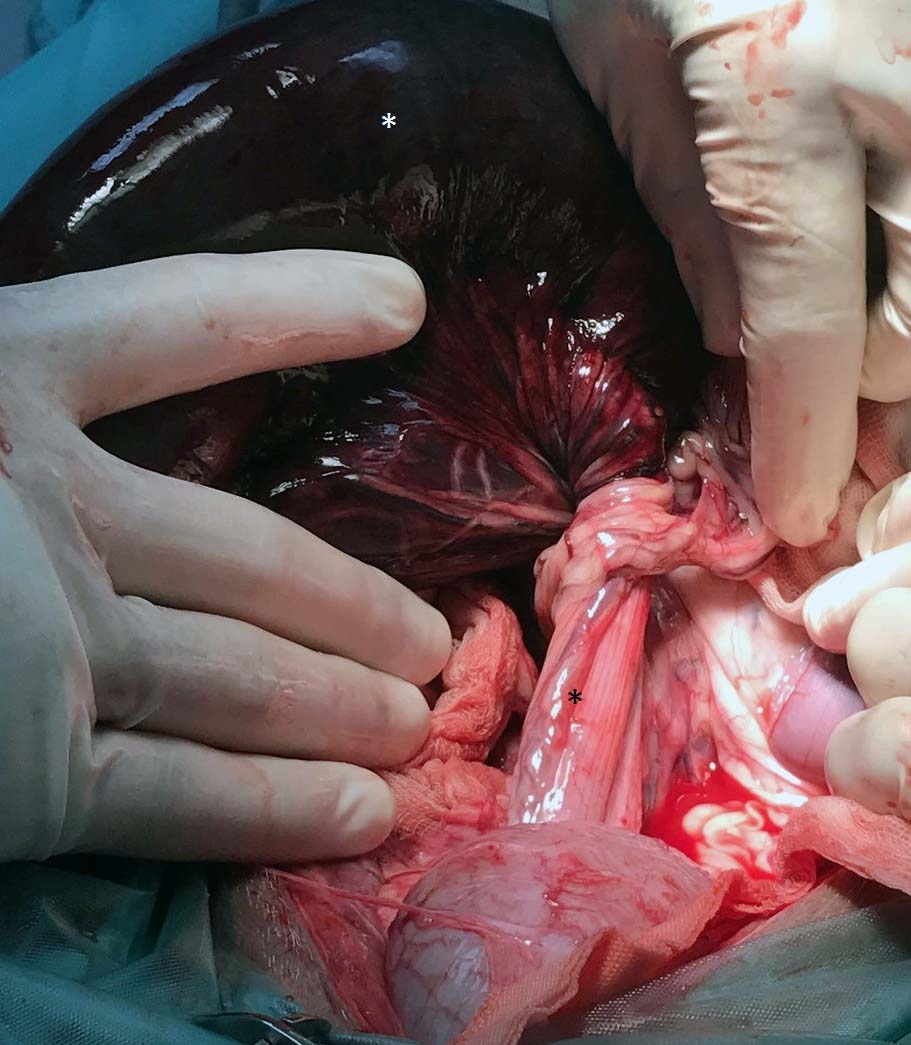

Figure 8. At laparotomy, a twist of more than 360° in the root of the mesocolon was confirmed. Stark contrast is present between the torsed colon (white asterisk) and the descending colon distal to the volvulus (black asterisk).

Colonic torsion in dogs is uncommon, but probably underdiagnosed. And it’s worth diagnosing: perhaps unexpectedly, the prognosis appears to be quite good after surgery.

As in the case recounted in this article, ultrasonographic features including a “whirl” sign, thrombosis of vessels in the mesocolon and devitalisation of the affected colon wall can be used to make a preoperative diagnosis. The case described appears to be the first detailed account of the ultrasonographic features of canine colonic torsion, or of an ultrasonographically detected “whirl” sign or “whirlpool” sign in veterinary species.

The published literature documents some 43 cases of colonic torsion in dogs (Aleksiewicz et al, 2015; Bentley et al, 2005; Carberry and Flanders, 1993; Endres et al, 1968; Gagnon and Brisson, 2013; Halfacree et al, 2006; Huber, 1994, Javard et al, 2014; Marks, 1986; Milner and Newington, 2004; Plavec et al, 2017; Reichle, 2013).

Common features among these cases include acute onset of abdominal discomfort, depression, vomiting, straining to defecate and variable deterioration in circulatory parameters.

In contrast to mesenteric volvulus, long-term survival after surgery is the rule rather than the exception: achieved in 34 out of 43 reported cases. Diagnosis has generally been confirmed at laparotomy after identification of dilated loops of intestine on radiography. In a single case, ileocecocolic volvulus was strongly suspected preoperatively on the basis of CT findings (Javard et al, 2014).

Specific ultrasonographic features allowing a preoperative diagnosis have not previously been reported to the best of the authors’ knowledge.

A four-year-old neutered female German shepherd dog was presented with a 48-hour history of depression, progressive inappetence, abdominal discomfort, ptialism, occasional vomiting and faecal tenesmus.

Prior history included several years of chronic, relapsing diarrhoea and vomiting. Previous abdominal ultrasound documented diffuse small and large intestinal wall changes.

Full thickness biopsies from duodenum, proximal and distal jejunum, and ileum revealed chronic enteritis with most severe changes in the distal jejunum and ileum. Reduced trypsin-like immunoreactivity suggested exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Pancreatic atrophy was confirmed on histopathology. Treatment with oral antibiotics, dietary modifications and pancreatic enzyme supplements did not achieve complete control of signs.

Six months prior to presentation, an acute deterioration with profuse vomiting necessitated surgical intervention, whereupon an ileocoecal impacton with foreign material was identified and an ileocecocolic resection performed followed by ileocolic anastomosis. Histopathology of the distal ileum indicated continued chronic inflammatory changes in addition to the acute impaction, while the caecum was grossly normal with only acute ulceration, haemorrhage, oedema and purulent inflammation from the foreign material.

Surgical recovery was uneventful and the patient was thriving with only paroxysms of diarrhoea until the current presentation.

Physical examination at the most recent presentation revealed the patient to be quiet, but alert and responsive. Rectal temperature was 38.3°C; heart rate 100bpm with regular rhythm; pulse quality good; and mucous membranes pink with refill time less than one second. The abdomen was tense on palpation and an abnormal, firm viscus was suspected in the caudal abdomen. Therapy was instigated with IV fluids, maropitant, paracetamol and buprenorphine. Diagnostic ultrasonography was performed.

The thorax proved unremarkable. A small, somewhat echogenic, abdominal effusion was present: predominantly in the caudal abdomen. Abdominal fat appeared locally hyperechoic in the caudodorsal abdomen. Liver, biliary tract, pancreas, adrenals, spleen and urinary tract were unremarkable.

The stomach was normally positioned, but hypomotile and dilated, with a large volume of fluid content (Figure 1). Small intestine appeared unremarkable, with the exception of the terminal ileum having previously been surgically excised.

Jejunal lymph nodes were unremarkable and the mesenteric vessels between them demonstrated blood flow on colour Doppler interrogation (Figure 2).

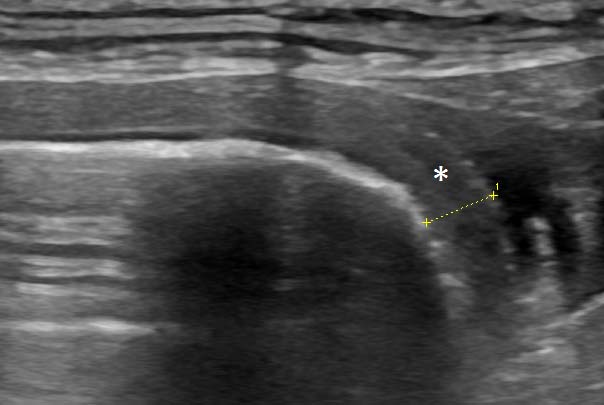

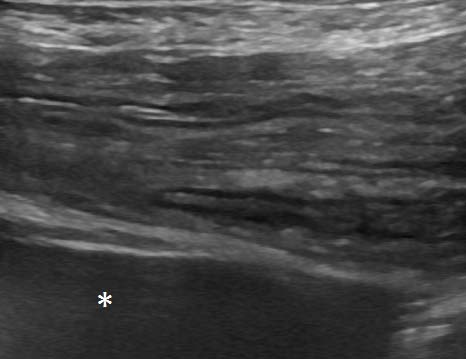

The majority of the colon was full of liquid content. The colonic wall in this part was thickened up to 4mm (Figure 3) and lacked distinct layering in some parts.

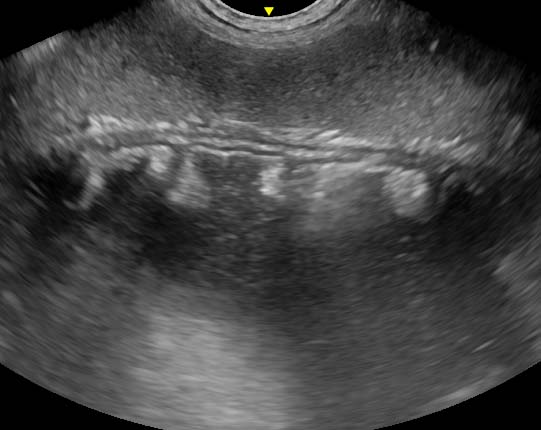

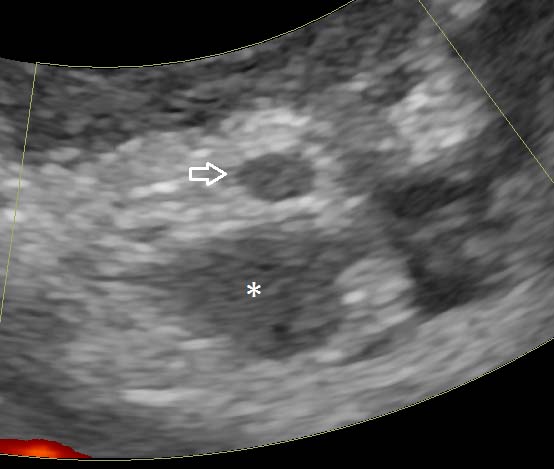

The descending colon could be followed aborally to a point in the caudodorsal abdomen where the lumen abruptly closed as the gut entered a tight “whirl” (Figure 4), in which the gut wall, adjacent mesentery and vessels converged in a spiral as viewed in a dorsal plane.

Caudal to this phenomenon, the colon and rectum exiting the twist were empty (Figures 5 and 6), and the wall appeared unremarkable.

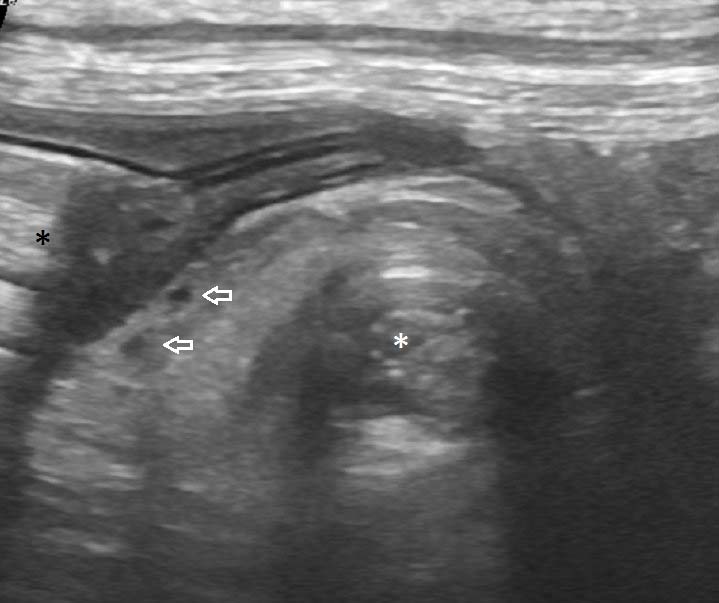

Large vessels, presumed to be caudal mesenteric artery and vein, involved in the “whirl” demonstrated no flow on colour Doppler (Figure 7): the lumina containing echogenic thrombi. Left colic lymph nodes were enlarged and hypoechoic.

A video of ultrasonography of the descending colon of this patient illustrating the “whirl” sign is available here:

A provisional diagnosis of colonic volvulus was made and, on this basis, the patient was taken to laparotomy without delay. Anaesthesia was induced with propofol to effect and maintained by isoflurane supported by CRI of 0.1mg/kg/hr methadone, 3.0mg/kg/hr lidocaine and 0.6mg/kg/hr ketamine.

Perioperative antibiotic 30mg/kg cefuroxime and 10mg/kg metronidazole with 10mg/kg paracetamol were given intravenously at induction. Cefuroxime was repeated after 90 minutes and metronidazole 12 hours post-surgery. Paracetamol was given every eight hours and continued after discharge.

A midline coeliotomy was performed from xiphoid to pelvis. A moderate volume of serosanguinous fluid was present, and preliminary examination showed distended and torsed colon (Figure 8), normal stomach, duodenum and proximal jejunum, with fluid dilated distal jejunum and proximal colon. Pancreatic tissue was notably diminished. The previous ileocolic anastomosis was identified in the right caudal abdomen and a short 10cm length of ascending colon entered into the twisted base of the mesocolon from the right side; the twist was anticlockwise from the surgeon’s view.

The volvulus included the ascending, transverse and descending colon, and appeared to be greater than 360°. The volvulus was not corrected prior to enterectomy to reduce release of endotoxins as the tissue was grossly non-viable.

Distal ileum and colon were isolated with bowel clamps, and the mesenteric vessels ligated with 3 metric polydioxanone before removal. Due to the dilation of the distal ileum, a direct end-to-end anastomosis was possible and completed with full thickness, simple continuous 2 metric polydioxanone.

It was not possible to close the mesenteric deficit, which was large enough not to cause entrapment. The abdomen was lavaged with five litres of warmed lactated Ringer’s solution and routinely closed.

Ventricular premature complexes were recorded during surgery and treated with intravenous boluses of 1mg/kg lidocaine.

Recovery was uneventful – after 48 hours the patient was discharged on a high-digestible, low-residue diet, and a source of probiotic and fibre. At the time of writing, the patient remains alive and well, and while still experiencing chronic diarrhoea, has passed normal formed stools post-surgery.

As regards canine colonic volvulus generally, this case is typical in most respects.

Increased risk among young to middle-aged large breeds generally, and German Shepherd dogs specifically, is well-documented. An association with a history of gastrointestinal disease generally, and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency specifically, has also been reported (Gagnon et al, 2013; Halfacree et al, 2006).

Almost universally in previously reported cases, a decision to undertake exploratory laparotomy relied upon a combination of unremitting clinical signs and plain radiography, although positive contrast retrograde colonography was employed by Milner and Newington (2004), and CT by Javard et al (2014).

A recent prospective analysis of the comparative utility of different imaging modalities in people with abdominal pain concluded that plain radiography was of limited value (van Randen et al, 2011).While CT may be regarded as gold standard, ultrasonography offers significant advantages over radiography in cases of “acute abdomen”, both in terms of information obtained and the practicalities of obtaining images.

The presence and nature of any abdominal effusion may be crucial to decision-making: ultrasound has greater sensitivity in detecting small volume effusions and can guide abdominocentesis (Henley et al, 1989).

Ultrasonography also has better sensitivity in diagnosing numerous important conditions, such as small intestinal mechanical obstruction (Sharma et al, 2011), acute pancreatitis and gallbladder rupture (Crews et al, 2009).

Disadvantages of ultrasonography in acute abdomen include reduced sensitivity in the detection of pneumoperitoneum, inter-operator variability, difficulty in remote interpretation of images, increased duration of image acquisition and, sometimes, pain on examination.

A few of the previously reported cases underwent abdominal sonography: non-specific findings, including dilated bowel segments and abdominal effusion, are described.

Sonographic evidence of mesenteric vessel thrombosis and intestinal wall devitalisation is strong circumstantial evidence for volvulus. Arterial thromboembolism in general is uncommon in dogs and isolated mesenteric arterial thrombosis even more so; potential alternative causes include infective endocarditis, neoplasia, other causes of disseminated intravascular coagulation, hyperadrenocorticism and hypothyroidism. None of these was considered likely in the present case.

Cranial mesenteric arterial thrombosis has been observed by the authors in mesenteric volvulus in dogs. A visible twist in the descending colon in conjunction with a “whirl” or “whirlpool” sign in the mesocolon, and thrombosis of the caudal mesenteric vessels, could, in the authors’ opinion, be considered diagnostic for colonic volvulus.

The descending colon is readily accessible to ultrasonographic examination and is consistently located immediately deep to the abdominal wall in the left caudal abdomen. Under normal conditions, the left colon follows a relatively straight course from the left sublumbar fossa caudally to the pelvic canal.

The term “whirl” or “whirlpool” sign has been used in human and veterinary medicine to describe the spiral appearance of twisted bowel, mesentery and vessels on CT or ultrasound when viewed in a plane of imaging perpendicular to the axis of rotation (Chow et al, 2014). Detection of such findings on ultrasonography does not appear to have previously been described in veterinary species.

Different authors use the terms in different ways. For example, Rokade et al (2011) uses “whirlpool” sign to describe a vascular phenomenon in human patients when colour Doppler demonstrates twisting of the superior mesenteric artery and vein around each other.

Some caution must be exercised in the interpretation of a “whirl” sign alone: both Chang et al (2012) and Blake and Mendelson (1996) describe human cases in which such findings were not associated with volvulus.

Specifically, adhesions and scarring following partial colectomy may present with degrees of “whirling”; although, vascular engorgement, thrombosis and pneumatosis intestinalis are not features in such scenarios.

Suárez Vega et al (2010) define a “whirl” sign as specifically involving both bowel and vessels, as seen in the present patient, and exclude cases in which either vascular or bowel alone appear twisted.

This case demonstrates a phenomenon suspected by Halfacree et al (2006) that, when the torsion involves the transverse and descending colon only rather than the cecum and colon in its entirety, then perfusion through the cranial mesenteric vessels remains unaffected. In cecocolic torsion, parts of the small intestine are often also ischaemic.