20 Jun 2023

The cat with three testicles – a case of interstitial cell tumour

Kate Parkinson discusses this unusual occurrence in a domestic shorthair feline patient that presented with cat bite abscess.

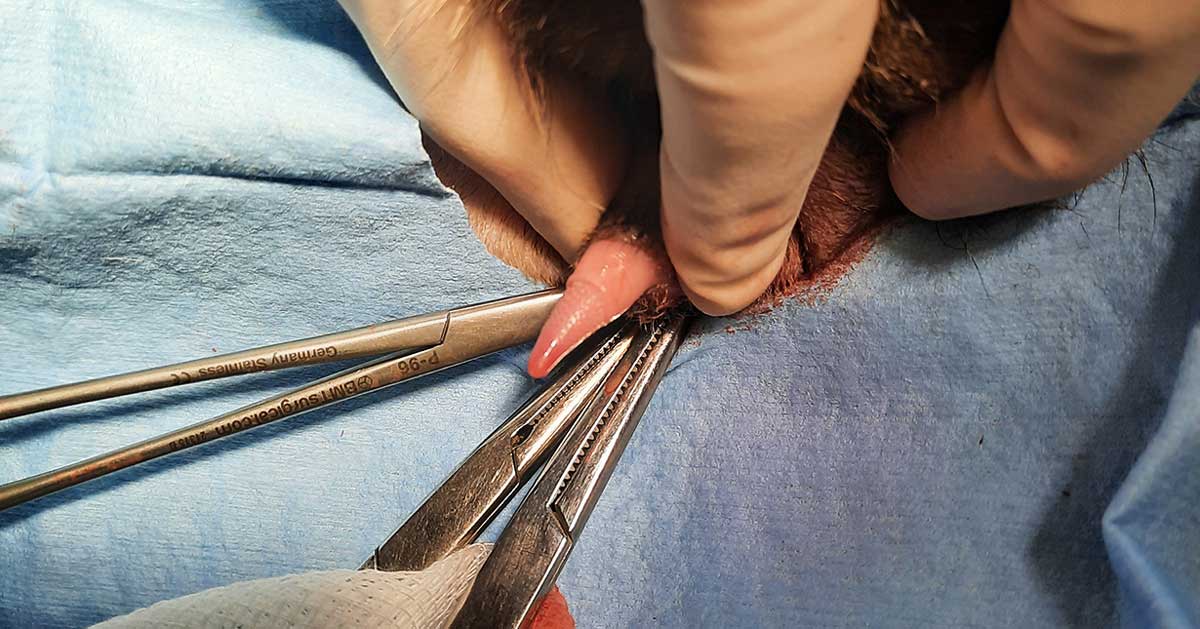

Figure 1. Penile barbs present in the previously castrated male cat.

Primary testicular tumours are rarely reported in castrated animals. Scrotal swelling may be noted on clinical examination. Differentials include haematoma, inflammation, trauma, neoplasia and – more rarely – fluid, testicular torsion, hernia, foreign bodies and polyorchy.

Testicular neoplasms include germ cell tumours (seminoma or teratoma), epithelial cell tumours (adenomas, carcinomas) and stromal cell tumours, including Sertoli cell tumours, and interstitial or Leydig cell tumours, as in this case.

Interstitial cells secrete testosterone and are responsible for secondary sexual characteristics in males. Most cases are seen in middle-aged to older cats and form spontaneously following neutering. As in this case, patients commonly present following development of male behaviours despite previous castration.

Interstitial cell tumours are usually primary and do not usually invade tissue. Resection is usually straight-forward, and diagnosis may be made following histological examination. Metastasis is unlikely, although cannot be ruled out completely due to the small number of reported cases, and the long-term prognosis is excellent.

In castrated animals, interstitial cell tumours may originate from testicular tissue transplanted during surgery and may, therefore, be considered an extremely rare complication of castration. Interstitial cell tumours should be considered as a diagnosis in previously neutered cats that present with scrotal swelling and tomcat-like behaviour following castration.

A male, neutered domestic shorthaired cat, aged seven years and nine months old, presented to the clinic with a cat bite abscess. While treating the abscess, the owner reported the cat was displaying behaviour similar to an uncastrated male and had developed a strong tomcat odour in the past few weeks.

On examination, the cat’s penis was found to be barbed (Figure 1) and palpable swelling was found in the right scrotal sac. This was unusual, as the cat had been castrated by the practice seven years previously.

The records were reviewed and showed no abnormalities. The castration had been carried out using a routine scrotal approach and both testicles were recorded as being removed. The cat had no other recent medical history, save for a bout of stress-induced cystitis, which was thought to be unrelated. Exploratory surgery was recommended.

Identification

Although the cat was unfortunately not microchipped, he had been registered with the presenting practice since his neutering at five months of age.

The owner had not moved and remembered the cat being castrated at the practice. Therefore, identification of the cat, although not microchipped, was assumed to be accurate.

Pre-surgical examination

The cat presented for surgery two weeks later. His temperature, pulse and respiration were all normal. The swelling in the right scrotal sac was unchanged (Figure 2).

The cat had the jowls and a well-muscled body typical of an entire male, as well as a barbed penis. A testicular remnant or tumour was suspected.

Pre-anaesthetic testing was offered, but declined as the cat was otherwise in good health. Due to financial constraints, it was not possible to establish testosterone levels prior to surgery.

Surgery

Pre-medication was administered with 0.02mg/kg acepromazine and 0.3mg/kg methadone. An IV catheter was placed and 0.2mg/kg meloxicam given subcutaneously. Anaesthesia was induced with IV propofol to effect. The cat was intubated and maintained with isofluorane.

The scrotum was incised and a mass of dark-coloured, solid matter was removed from the scrotal sac (Figure 3). No testicular tissue remnants were visible.

The tissue excised did not resemble testicular or spermatic tissue. Instead, it was homogenous and encapsulated, brownish in colour and extended down into the remnants of the vaginal tunic (Figure 4). The tunic was ligated with 2-0 monofilament suture material and the tissue was excised.

The scrotum was closed with a single absorbable monofilament cruciate suture. The cat was discharged the same day with an Elizabethan collar to prevent licking and the tissue was submitted for histological examination. The cost of the histology was covered by the practice as it was felt possible the swelling could have originated in a testicular remnant.

Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses for scrotal swelling include the following.

- Haematoma: common – especially following neutering (post-surgical complication).

- Inflammation: (dermal, subdermal, testicular). Includes superficial inflammation, such as scrotal dermatitis, orchitis and periorchitis. Rarely, feline infectious peritonitis may cause inflammation of the serosal surface of the tunics1.

- Infection: any skin infection can be located in the testicular skin. Likewise, any penetrating wound of the scrotum or testes may cause infection deep within the tissue. Post-surgical complications include infection – especially following postoperative self-trauma.

- Trauma: a common cause of testicular swelling, usually due to haematoma, testicular rupture or haematocoele (blood in the tunica vaginalis).

- Foreign body: intrascrotal foreign bodies are extremely rare, but may be found in trauma cases and gunshot wounds2.

- Fluid (hydrocoele): linked to ascites.

- Neoplasia (dermal, subdermal, testicular): any neoplasm or mass found in the skin can be found over the testicles. This includes lesions such as sebaceous hamartoma, sebaceous hyperplasia and trichoblastoma, as well as neoplasms such as adenomas and carcinomas. Testicular neoplasia includes interstitial or Leydig cell tumours, Sertoli cell tumours, seminomas and teratomas.

- Hernia: scrotal hernias are not usually seen in cats.

- Testicular torsion: torsion of a fully descended testes is incredibly rare in all species apart from the horse, but can be seen in cryptorchid testes in cats.

Polyorchy: although polyorchy (more than one testicle) is theoretically possible, it is extremely unlikely, with only a handful of cases being recorded in the literature3.

Histology and results

The mass was identified as an interstitial or Leydig cell tumour. Typically, neoplastic cell sheets and nests are supported by a fine connective tissue stroma.

Leydig cells have a large eosinophilic, vacuolated cytoplasm and a small, dark nuclei. The vacuoles are of varying sizes and appear optically empty. Mitotic figures are typically rare4. Tissue is often encapsulated, and no evidence of invasive growth is usually seen5.

Interstitial or Leydig cells are the primary source of androgens in males. They secrete testosterone and are located near the blood vessels6.

Interstitial tumours may be seen in the testicles, the epididymis and in an extra-testicular location5. They are uncommon in neutered animals, and more common in dogs than cats5.

In a study of 17 neutered dogs and cats (12 dogs and 5 cats), all 5 of the cats had interstitial cell tumours, while 11 of the dogs had Sertoli cell tumours and only 1 an interstitial cell tumour.

All 5 cats displayed tomcat behaviour, such as spraying and aggressiveness.

The mean age on presentation was 9 years (range 4 to 15 years), and the mean time following neutering was 8 years (range 4 to 12 years).

Cryptorchidism is an important factor in the development of testicular tumours in dogs, but cases are so rare in cats that the link between cats, testicular tumours and cryptorchidism is unknown7.

Interstitial cell tumours are considered primary neoplasms and not metastases. The tissue may originate from embryological testicular tissues, testicular tissue transplanted during surgery or as a result of testicular injury2.

The origin of the cells in this case is unknown. No metastasis has yet been recorded, but the number of recorded cases is so small that, although metastasis is unlikely, it is hard to rule out completely.

Prognosis

As previously mentioned, the numbers of interstitial cell tumours in previously neutered animals are small, but the prognosis is thought to be good.

In a study of 5 cats and 12 dogs5, 10 of the animals remained free of neoplasia, while the rest were lost to follow-up. All cats remained free of secondary sexual characteristics following surgery.

No reports of interstitial cell tumours metastasising exist. In this case, the cat went on to make a full recovery.

Conclusion

This was a very interesting case and one of only a handful of published reports of testicular neoplasms in cats.

The most common cause of interstitial cell tumours is thought to be small numbers of interstitial cells being transplanted from the testes at the time of neutering. These cells may survive if transplanted8, and later in life progress to neoplasia.

Although cell transplantation is thought to be a relatively common post-neutering complication, testicular carcinogenesis is extremely rare. Due to this, gentle handling of the testicles during neutering is recommended.

Interstitial or Leydig cell tumours should be considered as an unusual differential for a scrotal swelling in a previously castrated male.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Ardmore Veterinary Practice, Simon Bailey BVetMed, MRCVS, and Byron and his owners for permitting publication.

References

- Solano-Gallego L and Masserdotti C (2016). Reproductive system, Canine and Feline Cytology 313-352.

- Doxsee A, Yager JA, Best SJ and Foster RA (2006). Extratesticular interstitial and Sertoli cell tumors in previously neutered dogs and cats: a report of 17 cases, The Canadian Veterinary Journal 47(8): 763-766.

- Tucker AR and Smith JR (2008). Prostatic squamous metaplasia in a cat with interstitial cell neoplasia in a retained testis, Veterinary Pathology 45(6): 905-909.

- Asproni P, Millanta F, Lorenzi D and Poli A (2013) A Leydig cell tumor in a cat: histological and immunohistochemical findings, Case Reports in Veterinary Medicine, bit.ly/3WLhuSC

- Amodio J, Maybody M, Slowotsky C, Fried K and Foresto C (2004). Polyorchidism: report of three cases and review of the literature, Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 23(7): 951-957.

- Foster R (2013). Disease of the reproductive tract of the male cat, University of Guelph, bit.ly/3N5KWzD

- Montoya Chinchilla R et al (2013). Intrascrotal foreign body in a policeman aspirant, Eurorad, bit.ly/3oMPRfs

- Nayomi AP et al (2019). Autologous grafting of cryopreserved prepubertal rhesus testis produces sperm and offspring, Science 363(6433): 1,314-1,319.