7 Mar 2023

Testing for prevalent exotic parasites in imported dogs

Ian Wright outlines the most common pathogens found in pets brought into the UK from abroad, and how to screen for them.

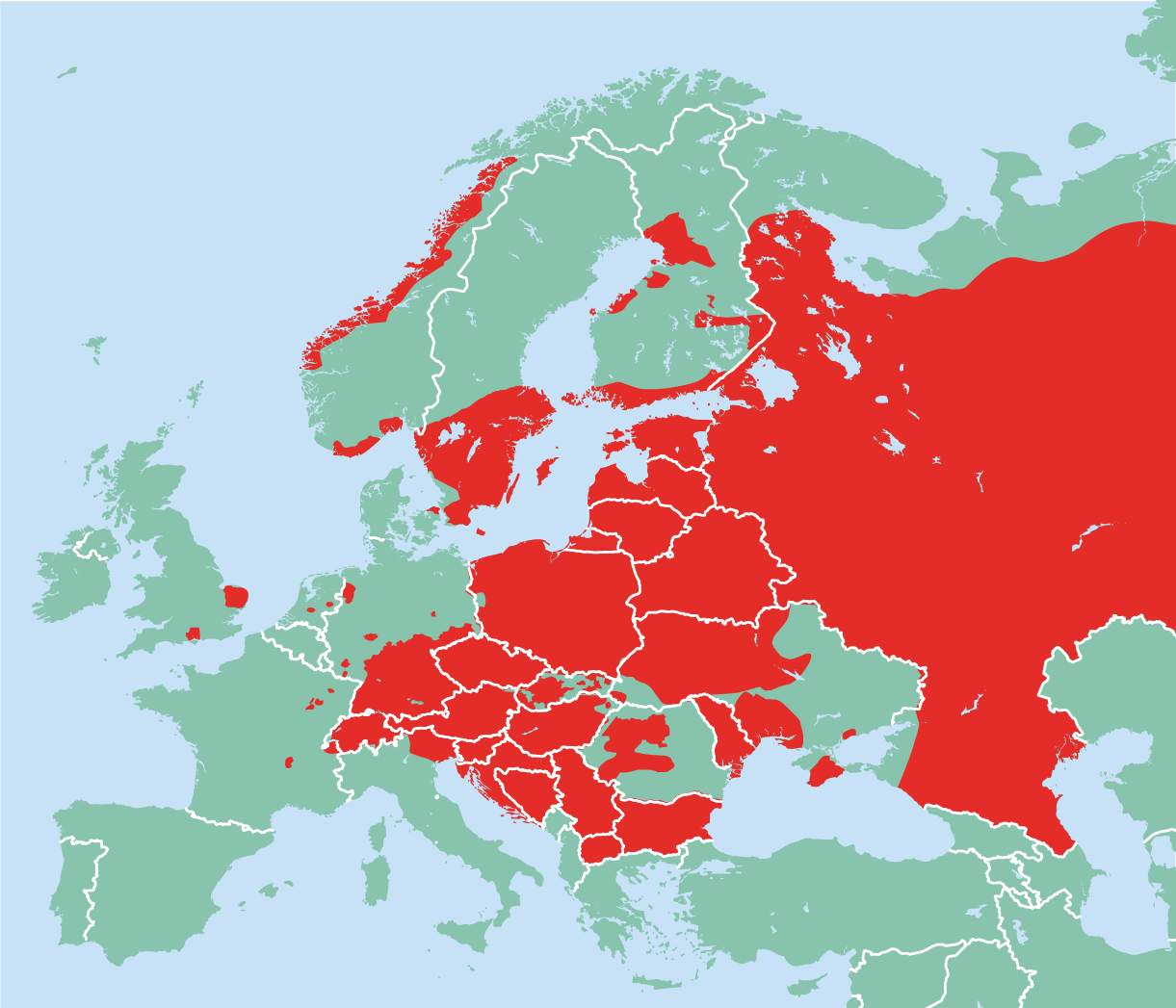

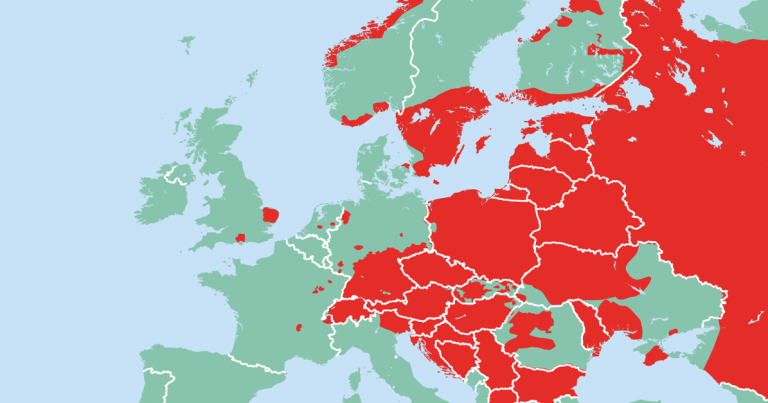

Figure 1. Distribution of human tick-borne encephalitis cases.

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic and Brexit, the numbers of pets rescued from abroad and imported into the UK has remained high.

This is happening in the face of expanding European and global parasite distributions, increasing the likelihood of exotic parasites being present in imported pets. Early recognition of clinical signs and diagnosis of exotic infections is, therefore, important to minimise potential zoonotic exposure, plan for treatment of any pathogens present and limit the risk of exotic parasites establishing in the UK.

To help manage these risks, the European Scientific Counsel for Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) UK and Ireland has formulated four key steps (the “four pillars”) when assessing imported pets on arrival in the UK:

- Check for ticks and identify any found. Identification of ticks allows the introduction and distribution of exotic tick species to be monitored in the UK, but also indicates which tick-borne pathogens the imported pet may have potentially been exposed to.

- Treat dogs again with praziquantel within 30 days of return to the UK and treat for ticks if treatment is not already in place. This will ensure that Echinococcus multilocularis is eliminated from imported pets, whatever the timing of their compulsory treatment. Tick treatment will increase the likelihood of attached ticks being killed if they are missed on examination.

- Recognise clinical signs relevant to diseases in the countries visited or country of origin. A thorough clinical exam of imported pets will identify relevant clinical signs for potential exotic infections.

- Screen for exotic parasites in imported dogs. Screening for parasites will lead to early diagnosis, preparing the owner for what could be a lifetime of potential management, any associated zoonotic risk and limiting wider spread through effective tick control.

When screening imported dogs for parasites, it is important to understand which parasites are arriving in the UK on imported dogs, which to prioritise for screening and their likely clinical presentations. Currently, no compulsory parasite testing for imported dogs exists. Whether if introduced this would be effective in preventing exotic parasite establishment and would be practical to implement depends on the parasite in question.

Exotic ticks and tick-borne pathogens

A number of exotic tick-borne pathogens have the potential to establish in the UK. Dermacentor reticulatus, the vector of Babesia canis, has long been established in Britain in west Wales, Devon, Essex and London (Medlock et al, 2017).

B canis is a cause of potentially life-threatening anaemia and thromboctyopaenia in dogs, and D reticulatus ticks present an opportunity for B canis to establish endemic foci if introduced via infected imported dogs or ticks. This occurred in the winter of 2014-15, when an endemic foci of B canis infection established in Harlow, Essex. The parasite was confirmed both in local Dermacentor ticks and in untravelled dogs (Phipps et al, 2016).

Recent studies have failed to find the parasite persisting in this foci, but found another infected tick in Devon, demonstrating the potential for further endemic foci to occur (Sands et al, 2022).

Rhipcephalus sanguineus ticks are not endemic in the UK, but often found on dogs imported from southern and eastern Europe, America, Africa and Asia. These ticks are capable of transmitting a wide range of tick-borne agents pathogenic to dogs, including Ehrlichia canis, Anaplasma platys, Hepatozoon species and Babesia vogeli.

Although it is unlikely that R sanguineus would currently establish outdoor endemic populations in the UK due to temperature, it can infest UK homes in a similar way to fleas (Hansford et al, 2018). This is a concern, as these ticks may also carry zoonotic pathogens such as Rickettsia conorii – the cause of Mediterranean spotted fever.

Ixodes species ticks, while already endemic across the UK, may carry tick-borne encephalitis virus if present on dogs that have visited or been imported from endemic countries (Figure 1). Its presence in imported ticks presents a risk of it establishing in the UK in the endemic Ixodes species population.

Common clinical signs associated with imported tick-borne disease include the following.

Anaemia and thrombocytopenia

Babesia species infection can lead to immune-mediated haemolytic anaemia in dogs with subsequent regenerative anaemias developing. These most commonly are acute and typically present with pale mucous membranes, icterus, fever and hepatosplenomegaly.

Associated depression and anorexia may be present, as well as dark brown urine associate with haemoglobinuria. Concurrent thrombocytopenia may be present with petechiation on the gums. Imported dogs with these signs should raise suspicion of Babesia species infection.

Thrombocytopenia is also a common sign in both acute and chronic ehrlichiosis. In both chronic babesiosis and ehrlichiosis, clinical signs may develop months or years after diagnosis.

A platys is a cause of cyclic thrombocytopenia in dogs, so this should be considered as differential diagnosis in dogs suffering from recurrent bouts of thrombocytopenia.

Lymphadenopathy and pyrexia

Many clinical tick-borne infections present with lymphadenopathy and pyrexia.

It is especially important to recognise these acute signs of E canis infection as, without treatment, it may progress to the chronic, often fatal form in dogs.

Neurological signs

Tick-borne encephalitis, and both acute and chronic ehrlichiosis, may present with signs associated with meningitis and meningoencephalitis. These include ataxia, seizures, paresis, hyperaesthesia, cranial nerve deficits and vestibular signs. These may present acutely or, in the case of chronic ehrlichiosis, months or years after initial infection.

Neurological signs in tick-borne encephalitis cases are progressive and often fatal. Zoonotic risk in the absence of tick vectors in households is minimal, but establishment of R sanguineus in homes presents the possibility of Rickettsia being transmitted by larvae and nymphs feeding on human occupants.

Screening options

Blood smear examination carries a high sensitivity and specificity for H canis detection and B canis in clinical cases. Screening for E canis and A platys, however, requires PCR or serology testing.

Serology is highly sensitive and specific for detecting exposure to the parasite. Quantitative serology is useful in the case of E canis infection, where a fourfold increase in test titres taken two weeks apart is indicative of active infection.

Blood PCR is also a highly specific and sensitive test for both parasites.

Case for compulsory testing and/or compulsory tick treatment

While compulsory screening for tick-borne pathogens would be useful in assessing the management needs of individual dogs, the large numbers of pathogens involved makes compulsory screening impractical.

In practice, the cost of testing for a range of tick-borne pathogens can be reduced by combination patient side tests, in-house PCR testing or diagnostic packages at external labs. From a biosecurity point of view, novel tick-borne pathogens are more likely to be introduced via ticks rather than infected dogs.

Compulsory tick treatment would reduce this risk, and highlight the need for tick treatment to clients and importing charities. Ticks may also be introduced by other routes, however, including migratory birds, vehicles and clothing. This means it is unlikely to be reintroduced as a legal requirement.

Tick treatment and checking for ticks should still be recommended for dogs travelling abroad and entering the UK.

Leishmania infantum

Increasing numbers of Leishmania-positive dogs are being imported into northern European countries including the UK, with a significant percentage of dogs tested being positive (Miró et al, 2022).

While the sand fly vector is not thought to be endemic in the UK, infected dogs in the UK also pose an unquantified transmission risk, as horizontal transmission has been recorded in the absence of the sandfly vector (McKenna et al, 2019; Wright and Baker, 2019).

It is unknown how these infections occur, but it has been speculated that transmission may occur through dog bites (Daval et al, 2016), or through mechanical fly transmission. Endemic foci can also be maintained through venereal and congenital routes, as well as via blood transfusion.

If large numbers of dogs are kept together in the UK or in densely canine populated areas then the odds of transmission by these routes will increase. This is a concern, as many of the Leishmania-infected dogs confirmed in the UK are in urban areas of the south of England (Shaw et al, 2009; Silvestrini et al, 2016).

Leishmaniosis is chronic in nature, with a variety of presentations and periods of remission. Signs are due to immune complex deposition in various organs and include lymphadenopathy, cutaneous signs (such as generalised and focal alopecia, hyperkeratosis, dermal ulcers and peri-ocular alopecia), weight loss, splenomegaly and renal signs associated with glomerulonephritis. Less commonly, polyarthritis, thrombocytopaenia, ocular inclusion bodies, uveitis and neurological signs associated with spinal and CNS granulomas may be present.

These signs will develop months, and in some cases years, after initial infection.

Zoonotic risk in the absence of the sand fly vector is very small, but still possible, so good hygiene should be maintained around infected dogs exhibiting clinical signs.

Screening options

If lymphadenopathy or active skin lesions are present then samples can be taken from lymph nodes or affected skin.

Fine-needle aspirate techniques can unambiguously demonstrate the presence of the amastigote stage of Leishmania in Giemsa or Diff-Quik stained smears, but carry a relatively low sensitivity.

Histology performed on tissue samples carries a higher sensitivity, with lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory reaction associated with macrophages infected with a large number of Leishmania amastigotes being the main finding.

Serological detection of specific anti-Leishmania antibodies can be used for routine screening. Specific antibody responses in dogs take time to develop, so it is useful to test dogs both on arrival and around six months later.

Immunofluorescence assay and ELISA tests are commercially available. They do not confirm or rule out active infection, but quantitative serology allows the size of response to be measured. If this climbs over time in non-endemic countries then it indicates active infection is present, and can act as a indicator that clinical leishmaniosis is present or about to develop.

These assays may cross react with antibodies to Trypanosoma cruzi, another Trypanosome protozoan that infects dogs in the Americas.

PCR allows detection of Leishmania DNA in the animal’s tissue. PCR runs on aspirates or biopsies of skin or lymph node in clinically affected dogs carry a higher sensitivity than samples collected from blood or urine. PCR run on conjunctival swabs can also carry a high sensitivity, but tends to be lower when antibody titres are low.

It is, therefore, not the best option to confirm infection if antibody titres are low or borderline.

Case for compulsory testing

Pet travel and importation rules have focused on the prevention of novel zoonoses entering the UK and establishing here. Leishmania fits this profile, and compulsory testing would be beneficial to monitor positive dogs and plan for their long-term management.

While direct infection from Leishmania-positive dogs is unlikely, if the sandfly establishes in the UK through the effects of climate change then the risk of endemic establishment and zoonotic risk would also grow.

No single agreed test exists for Leishmania screening, however, and all have variable sensitivities depending on the level of infection and the individual patient. This reduces the benefit of compulsory testing for biosecurity.

Making Leishmania infection reportable for surveillance purposes, however, would be highly beneficial.

Dirofilaria immitis (heartworm)

Increasing numbers of heartworm cases are being recorded in imported dogs in northern Europe, including the UK (Miró et al, 2022).

Mosquitoes capable of transmitting Dirofilaria immitis are present throughout northern Europe, but the risk of the parasite establishing in these countries is low as the climate is too cold to allow D immitis to complete its life cycle. Climate change, however, may allow establishment in the future. Recognition of clinical signs and screening is also important for early diagnosis and prompt treatment, which improves the prognosis for the individual patient.

Coughing, tachypnoea, dyspnoea and exercise intolerance are the most common clinical signs seen in infected dogs. Acute clinical signs are associated with thromboembolism, subsequent pulmonary hypertension and caval syndrome. Worm death can also lead to thromboembolism and anaphylaxis.

Although D immitis is zoonotic via exposure to infected mosquitoes, no zoonotic risk from heartworm currently exists in the UK as the parasite is not present in mosquitoes.

Screening options

Testing for uterine antigen secretions of female adult D immitis heartworms is a highly specific diagnostic test in infected dogs and highly sensitive in cases of significant worm burdens.

A second test in newly imported animals six months after arrival is useful to rule out infection. The modified Knott’s test for microfilaria concentrates microfilariae in the blood and is a useful test in positive dogs to quantify the numbers of circulating microfilariae.

Dogs with high circulating numbers are more likely to suffer anaphylaxis if treated with macrocyclic lactones. Microfilariae of D repens will also be detected by this method.

Adult worms can also be detected by ultrasonography if the pulmonary arteries are tracked to the bifurcation.

Case for compulsory testing

The low chance of D immitis establishing in the UK, the need to test dogs six to nine months after entry and the absence of significant zoonotic risk means that testing is unlikely to become compulsory.

Recommending screening, though, remains vitally important for the health of the individual dog.

Brucella canis

Recent recorded cases and risk of establishment

The UK is considered to be free of B canis, but increasing concern exists that increasing numbers of positive dogs are being imported from endemic countries. Two clinical cases were reported in 2017 (Whatmore et al, 2017) and in 2022, a human case contracted from an imported dog was reported.

Infected dogs may be subclinical. Clinical infection is typically associated with reproductive abnormalities, including infertility, abortion, endometritis, epididymitis, and orchitis and scrotal oedema. A wide range of non-reproductive conditions can also occur, though, including chronic uveitis, endophthalmitis and discospondylitis. Lymphadenitis is common along with non-specific clinical signs such as lethargy, exercise intolerance, decreased appetite and weight loss.

Transmission occurs via reproductive fluids, but is also shed in urine, blood and saliva. Once dogs are infected, infection either persists for two to three years before elimination by the immune system or lifelong infection establishes.

Human cases are rare, with between one and two hundred cases a year reported in the US, but the consequences of zoonotic exposure can be significant – especially in the immune suppressed.

Diagnosis

Where infection is suspected, this should be highlighted in laboratory paperwork so appropriate precautions can be taken when handling samples. Imported dogs with relevant clinical signs should also be handled with appropriate PPE.

Blood antibody testing carries a higher sensitivity than PCR – and, therefore, a more useful initial screen – but only demonstrates exposure rather than active infection. This then needs to be confirmed by PCR.

Antibodies take time to develop and imported dogs should ideally be tested before UK entry, and then from three months after arrival. It is important, though, to discuss appropriate testing, with the laboratory being used as various antibody tests are available.

Brucellosis in dogs is reportable and should be reported via local APHA veterinary investigation centres. A strong argument still exists for euthanising positive dogs, given the difficulties in eliminating infections and the zoonotic risk. Owners should be prepared for this possibility when testing is discussed.

Alternatively, as a minimum, they should be neutered with preoperative and postoperative antibiotics.

Infected dogs must not be used for breeding, should not live with immune-compromised individuals and should not interact with other dogs.

Case for compulsory testing

A strong argument exists for compulsory testing to be introduced. It is a significant zoonosis that impacts dog breeding and, realistically, could establish in the UK. These risks are immediate for B canis as infection can occur through contact with bodily fluids, as well as venereal and congenital routes.

Veterinary and animal welfare groups continue to argue for a compulsory test either before importation or on arrival.

Parasites identified directly through clinical examination

Some worms and worm-like exotic parasites of concern may be identified through clinical examination alone. These include the following.

Thellazia callipaeda

Thellazia callipaeda is a vector-borne eye worm with hosts including dogs, cats and humans. The first confirmed cases in the UK were recorded in dogs imported from Romania, Italy and France (Graham-Brown et al, 2017).

Should T callipaeda be introduced to the UK, its primary fruit fly vector Phortica variegata has been recorded in the UK with conditions favourable for spread. Although often subclinical, ocular thelaziosis can commonly cause conjunctivitis, keratitis, ephiphora, eyelid oedema, corneal ulceration and blindness.

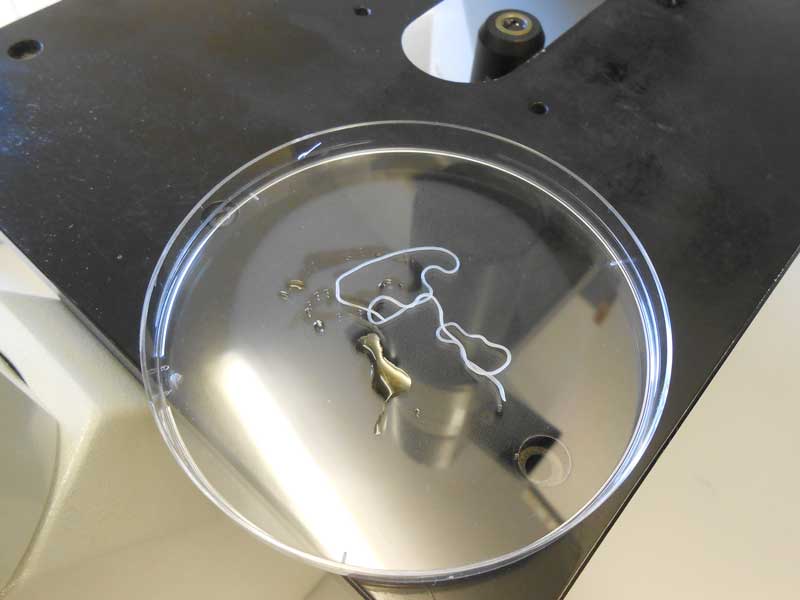

Close examination of the conjunctiva will often reveal worms (Figure 2) actively moving on the surface, and checking is vital in all imported cats and dogs to detect low-grade, or subclinical infections to prevent vector exposure. Early diagnosis will also improve treatment outcomes.

Dirofilaria repens

The first cases of the skin filarial nematode D repens in the UK were dogs imported from Corfu and Romania (Wright, 2017; Agapito et al, 2018).

While not highly pathogenic, D repens is a zoonosis and could be transmitted by mosquitoes endemic in the UK. D repens infection in dogs appears to be spreading across Europe, with a corresponding increase in zoonotic cases.

Cases of D repens infection are most commonly subclinical, but clinical signs associated with infection can occur. Dermatitis is the most common clinical presentation as multifocal nodules in the skin or papular dermatitis. Less commonly, hyperkeratosis, crusting, distinct nodules, acanthosis and secondary pyoderma can occur. Adult worms may be present in these nodules (Figure 3).

Signs may also develop from migration of worms to other parts of the body, including conjunctivitis, anorexia, vomiting, fever, lethargy and lymphadenopathy.

Ocular migration of worms into the vitreous is uncommon, but does occur and, therefore, D repens should be considered as a differential if worms are visualised there, and in dogs presenting with dermatitis that have travelled abroad.

Linguatula serrata

A number of nasal pentastomid L serrata (tongue worm) cases have been seen in the UK, imported from eastern Europe and Turkey (Figure 4). Infection is acquired from the consumption of raw meat and offal in endemic countries. L serrata is a zoonotic infection with humans acting as intermediate, as well as definitive hosts, and may, therefore, become infected through ingestion of eggs from nasal secretions and faeces.

Most cases of infection in dogs and cats are subclinical. However, large burdens can lead to rhinitis and nasopharyngitis, with associated chronic sneezing and/or coughing, purulent nasal discharge and epistaxis.

It is vital these signs are detected early in affected dogs to limit zoonotic exposure to owners and others in contact who may ingest infective eggs in nasal discharge, or from faecal contamination.

Adult worms may be expelled from the nose during sneezing or discovered during endoscopy.

The APHA, in collaboration with ESCCAP UK and Ireland, is offering free-of-charge morphological identification of suspected cases of T callipaeda, D repens, and L serrata seen in veterinary practices in England and Wales.

Sample submissions must be accompanied by full clinical history to qualify for free testing. Further information on how to submit them can be found via the APHA.

Summary of screening tests

For dogs imported into the UK, ESCCAP UK and Ireland would recommend the following tests:

- Leishmania – quantitative serology with option to confirm by PCR or sample clinically affected sites.

- Heartworm – antigen blood test.

- Ehrlichia canis and Anaplasma – serology or PCR.

- Hepatozoon canis – blood smear or PCR.

- Babesia – PCR.

- Brucella canis – serology with infection confirmed by PCR. Consult your external laboratory for suitable test.

- Quantitative serology for Leishmania and heartworm antigen testing should be repeated six months after entry into the UK.

Conclusion

The growing trend of importation of rescue dogs from abroad means it is increasingly likely veterinary professionals will encounter exotic pathogens that present a health risk to individual dogs, the public and UK biosecurity as a whole.

Veterinary professionals have a vital role in assessing imported dogs for evidence of parasitic infection and putting effective preventive measures in place.

Screening tests form a vital part of early exotic parasite detection and, hopefully in time, some of this testing will be made compulsory before entry into the UK.