1 Aug 2021

Taking control of worms: prevention protocols and education

Image © crevis / Adobe Stock

Worming is a fundamental component of a preventive health programme for pets. The serious implications of inadequate worming for both animal health and a zoonotic risk means it is essential to ensure owners understand the importance of parasite control.

Vet nurses have the skills and knowledge to routinely provide expertise on the topic. This article aims to provide an overview of worming including environmental factors, prevention, treatment and education.

It may be impossible to eliminate worm eggs from the environment, but treatment of the infection in primary hosts and good hygiene reduces transmission and zoonotic risk.

Choosing the appropriate worming treatments and frequency means determining which parasites pose a threat to an animal in a geographical area. An assessment should establish the lifestyle of the pet and consider the environment that it resides in so the client can be advised appropriately on the correct worming protocol.

An active adult dog or cat that hunts, scavenges and is regularly outdoors – working dogs or farm cats, for example – will have a different requirement to an animal that is walked on a lead or spends a lot of time indoors. Puppy and kitten worming protocols will require a completely different approach. This assessment will determine the best choice of anthelmintic product, spectrum of anthelmintic activity and frequency of administration.

The following factors should be considered when devising a worming programme:

- age

- health status

- lifestyle

- nutrition (RAW feeding)

- reproductive status

- travel history (domestic and international)

- access to farm land

The European Scientific Counsel Companion Animal Parasites (ESCCAP) recommends worming programmes are individually based on a risk assessment based on target groups A to D in dogs and A to B in cats (ESCCAP, 2021).

Good personal hygiene should be encouraged – especially for children – and advice should include handwashing after handling, the discouragement of face licking, washing animal bowls separately and ensuring sandpits are covered. Faeces should be removed regularly to reduce environmental contamination with infective parasite stages, and grooming and the examination of pets regularly prevents the risk of coat contamination with worm eggs.

A study on washing pets’ paws and owners’ shoes on return from walks found 19.4% of dogs’ paws and 11.4% of people’s shoes had Toxocara eggs detected on them (Panova and Khrustalev, 2018).

Nematodes (roundworms)

The term roundworm refers to all nematodes, but it can be used to refer specifically to the ascarid group of nematodes:

- Toxocara canis

- Toxocara cati

- Toxascaris leonina

Roundworms are worms of varying sizes that live in the intestine of their host. They attach themselves via their lip disks to the wall of the intestine and feed on mucous, blood or intestinal contents.

Most roundworms have a direct life cycle and no intermediate host. However, some, such as lungworms, may have one, while others can have a paratenic host. The ingestion of the paratenic host – for example, a mouse – can lead to direct infection of the final host.

The larvae frequently travel through the body while they develop, with the final larval stage returning to the intestines, where they metamorphose into adult roundworms and begin egg production.

The common roundworms of dogs and cats are important in companion animal medicine as pathogens, and as a significant zoonotic threat in people.

To reduce roundworm transmission to the puppies, pregnant females can be given macrocyclic lactones on the 40th and 55th day of pregnancy or fenbendazole daily from the 40th day of pregnancy, continuing to 2 days postpartum (ESCAAP, 2021).

ESCAAP (2021) recommends a single treatment of emodepside spot-on is used in a pregnant queen approximately seven days before expected parturition, as this prevents lactogenic transmission of T cati larvae to the kittens.

The recommended protocol is to worm monthly from two weeks of age in puppies and three weeks of age in kittens (ESCCAP, 2021). This is because T canis/T cati is usually present in puppies and kittens from these ages. It is essential to worm from an early age because Toxocara causes serious diseases in young animals and almost all will be infected. Puppies should receive two-weekly treatments until they are 12 weeks old, with protocols being reduced to monthly treatments until they are six months old, and then three-monthly treatments (ESCCAP, 2021).

Kittens should begin a fortnightly worming programme from three weeks of age (ESCCAP, 2021), this is because prenatal infection does not occur in kittens. Treatment should continue every two weeks until weaning, then monthly until six months of age. A programme should then be developed according to a cat’s lifestyle. Treatments should be given according to the manufacturer’s recommendations

For adult dogs and cats, ESCCAP (2021) recommends an individual risk assessment for each animal to determine whether anthelmintic treatment is necessary, and how often. Current information suggests annual or twice-yearly treatments do not have a significant impact on preventing patent infection within a population. Therefore, a treatment frequency of at least four times per year is a general recommendation. However, as the prepatent period for Toxocara is a little more than four weeks, monthly treatments minimise the risk of patient infections.

Lungworm

Angiostrongylus vasorum (lungworm or French heartworm) is a potentially life-threatening metastrongylid nematode that inhabits the right ventricle of the heart, and the pulmonary arteries in dogs, foxes and other carnivores. This is in contrast to the rest of the lungworm family, which mainly reside within the bronchi/bronchioles or the lung itself.

A vasorum should not be confused with the heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis), which also resides in the heart. The lungworm has an indirect life cycle that involves at least two different hosts: gastropod molluscs (intermediate host) and canids (definitive host).

The definitive host becomes infected after ingesting the intermediate host, slugs and snails that carry the lungworm larvae (L3). Infection could also potentially occur after swallowing the slime of an infected slug (Conboy et al, 2015).

Molluscs can be extremely small, and dogs can inadvertently ingest them when eating grass, drinking from outdoor puddles and water bowls, or while playing with toys. Parasite studies have highlighted its spread across the UK, with prevalence in foxes having risen from 7% in 2005 to 18% in 2014 (Taylor et al, 2015).

The life cycle of A vasorum is indirect, with dogs/foxes becoming infected when they ingest the intermediate host.

The adult worm resides in the right side of the heart and pulmonary arteries of infected animals. The female worm then releases eggs, which are carried in the bloodstream to the lungs, where they develop into first stage (L1) larvae. The L1 larvae burrow through the walls of the alveoli of the lung, and from there are eventually coughed up and swallowed, and passed out into the environment with the faeces, where they can infect slugs and snails.

Further development to L3 takes place within the mollusc. Following ingestion of the mollusc, the larvae are released, subsequently infecting the dog. The larvae then penetrate the intestinal wall and develop further within the lymph nodes (L5 larvae), which then migrate via the liver and caudal vena cava back to the right side of heart, where development into a new adult worm takes place. The time taken from ingestion of an infected slug or snail to an adult worm being present in the dog’s heart is on average 38 days to 57 days.

The anthelmintic products available as directed by the veterinary surgeon are:

- Imidacloprid/moxidectin – licensed for the treatment and prevention of angiostrongylosis, it eliminates fourth-stage larvae and immature adults (L5).

- Milbemycin oxime/praziquantel and afoxolaner/milbemycin oxime – licensed for the prevention of angiostrongylosis when used monthly, these products reduce the level of infection of L5 and adult worms.

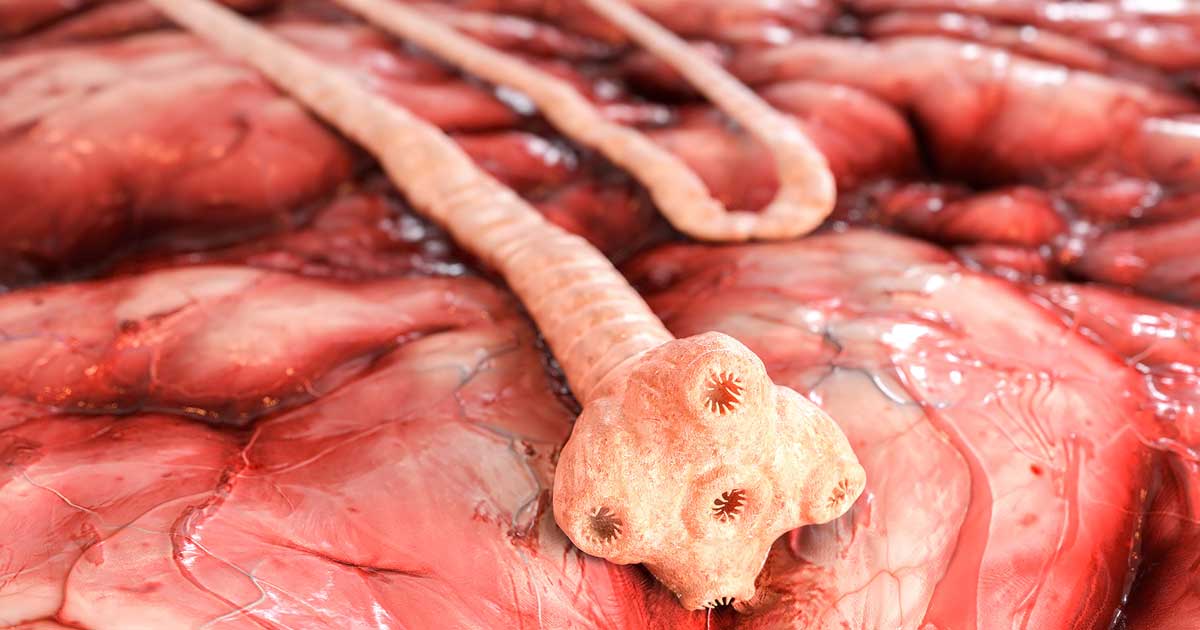

Cestodes (tapeworms)

Tapeworms are flat, ribbon like shapes that are divided into segments, which parasitise the small intestine and absorb nutrients from the final host through the surface of their bodies. They consist of a scolex (head), which is an attachment organ, a non-segmented neck region and a constantly regenerating series of segments (proglottids). The entire chain of segments (strobila) can grow to several metres long.

The mature tapeworm segments are filled with eggs, and individual segments break off and pass via the dog’s anus into the environment. The neck region constantly generates new segments to replace the mature proglottids that have been shed.

Tapeworms reproduce in intermediate hosts, such as fleas or the chewing dog louse (Trichodectes canis), which act as effective transmitters of tapeworm infestation. Tapeworms do not cause harm to their hosts, unless present in large numbers; however, their treatment is important for hygiene reasons and because some species are zoonotic.

Tapeworms, both in their fully grown and larval (cystic) stages, pose a threat to the health of the animal, but also humans when they act as accidental hosts if eggs are ingested.

The larvae infiltrate the gut wall, and are circulated throughout the body via the blood and the Iymph system. In certain organs of the intermediate host, the larvae develop into an infective cyst. This cyst contains a rudimentary scolex, which may then be ingested by the final host (dog, cat) when it ingests the intermediate host. In the intestinal tract of the final host, the scolex becomes exposed and attaches itself to the intestinal mucosa, where it develops into an adult.

Three main types of cestodes exist:

- Dipylidium caninum

- Echinococcus granulosus

- Taenia species

The risk of tapeworm infestation is dependent on lifestyle, feeding habits and geographical location. While tapeworm infestation has little clinical impact on the dog, serious consequences on meat and offal condemnation can be associated with cysts from E granulosus and Taenia species.

Most dogs on a commercial diet and outside an endemic area are at a lower risk and only require quarterly treatments. Dogs living in endemic areas, fed unprocessed raw meat, that hunt or have access to offal and carcasses are high risk, and should be treated every four to six weeks with praziquantel. Infestation risk from D caninum can be prevented with effective flea control (ESCAAP, 2021).

Educating clients

VNs play a vital role in the education of clients on parasite control. VNs often have trusting relationships with their clients; building on this can promote communication and confidence of pet owners in the recommendations provided to them.

Many clients feel more comfortable discussing parasite prevention with a VN as they are perceived to be more approachable and may have more time to offer the client (Tottey, 2015). Therefore, VNs are ideally placed to proactively convince owners of the importance of compliance to achieve an optimal treatment outcome.

Pet health plans can be a great way to actively encourage owners to take up regular parasite prevention. Puppy and kitten owners may be considered as the easiest group of clients to sign up to the practice health plan, which can encourage regular parasite prevention and therefore improve compliance.

Conclusion

VNs have an integral role in implementing individualised parasite control plans and educating clients on the importance of adequate control, the benefits to the pet, and how to employ and administer suitable control measures, according to the risk levels.

- Reviewed by Hollie Spurr BVM, BVS, MRCVS