4 Sept 2017

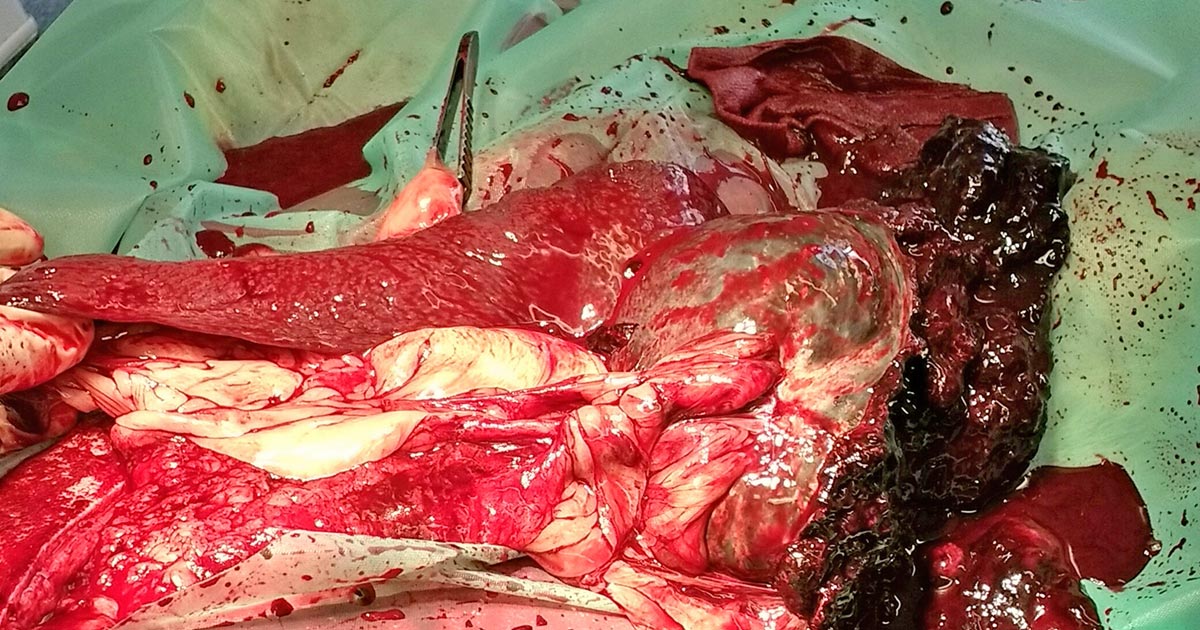

Figure 1. Splenic rupture.

A ruptured spleen (Figure 1) is a common emergency situation that will present as a collapsed patient with obvious signs of decompensated shock.

An elevated heart rate, elevated respiratory rate, pale mucous membranes, slow capillary refill time (more than two seconds), cold extremities, weak pulse, low temperature, lethargy and collapse are all the signs of a patient in serious trouble. A history will often rule out the possibility of toxin ingestion.

Oxygen supplementation is the first port of call for these patients. Our aim is to increase the percentage of inspired oxygen as to provide adequate tissue perfusion, even though the patient has a depleted circulating blood volume.

The vet may perform an abdominal-focused assessment using a sonography for trauma ultrasound scan to confirm free fluid and abdominocentesis, in turn, confirming the presence of haemoabdomen.

The patient will need to be stabilised with either a fluid bolus of Hartmann’s solution (20ml/kg for 20 minutes and reassess) or whole blood transfusion. Always ask if the pet has had a previous transfusion before administering blood.

Care must be taken when using blood products to identify any signs of a transfusion reaction early. If not body temperature-ready, warm the fluids/whole blood to at least room temperature prior to administering to the patient, to reduce the risk of hypothermia.

Also, if possible, a full blood haematology panel and biochemistry panel should be carried out prior to treatment to help show any signs of improvement or deterioration in the patient’s condition. At the very least, a PCV, total protein and lactate should be recorded, along with all vital signs.

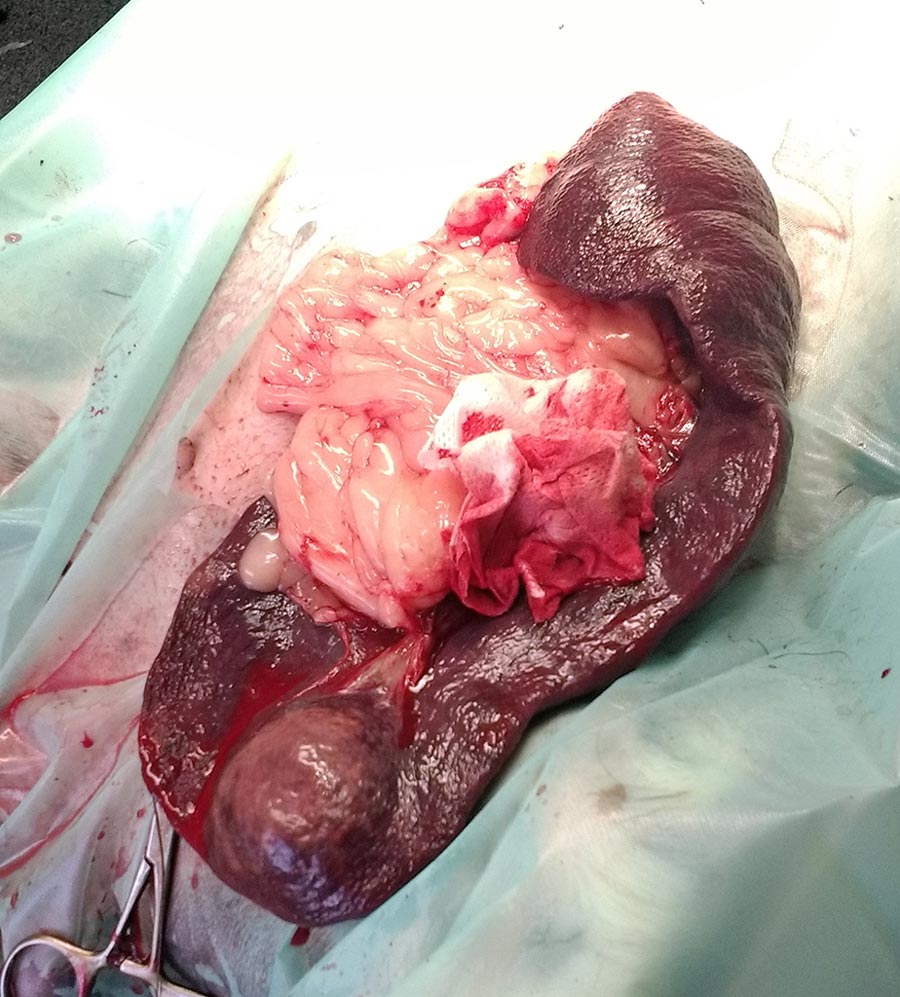

Autologous transfusions (Figure 2) can be performed during surgery when a donor patient is not accessible or insufficient time is available. Sterile collection of the blood is essential, with the use of a filtered-giving set reducing the risk of thrombus formation in the patient.

Remember, Hartmann’s solution must never be given through the same line as whole blood products, as this increases the risk of thrombus formation.

Malignancy is the most common aetiology of splenic ruptures, with haemangiosarcomas (Figure 3) being the most common. Trauma and nodular hyperplasia may also cause splenic rupture (Murgia, 2016).

Splenic haemangiosarcomas commonly metastasise (Figure 4) either to the lungs or other organs, such as the liver. Radiographs, left and right lateral, plus dorsoventral and ventrodorsal, views should be taken during recovery to spot any metastases.

Thrombocytopenia, anaemia and cardiac arrhythmias are the main risk factors associated with perioperative death in patients presenting with splenic masses.