19 Oct 2022

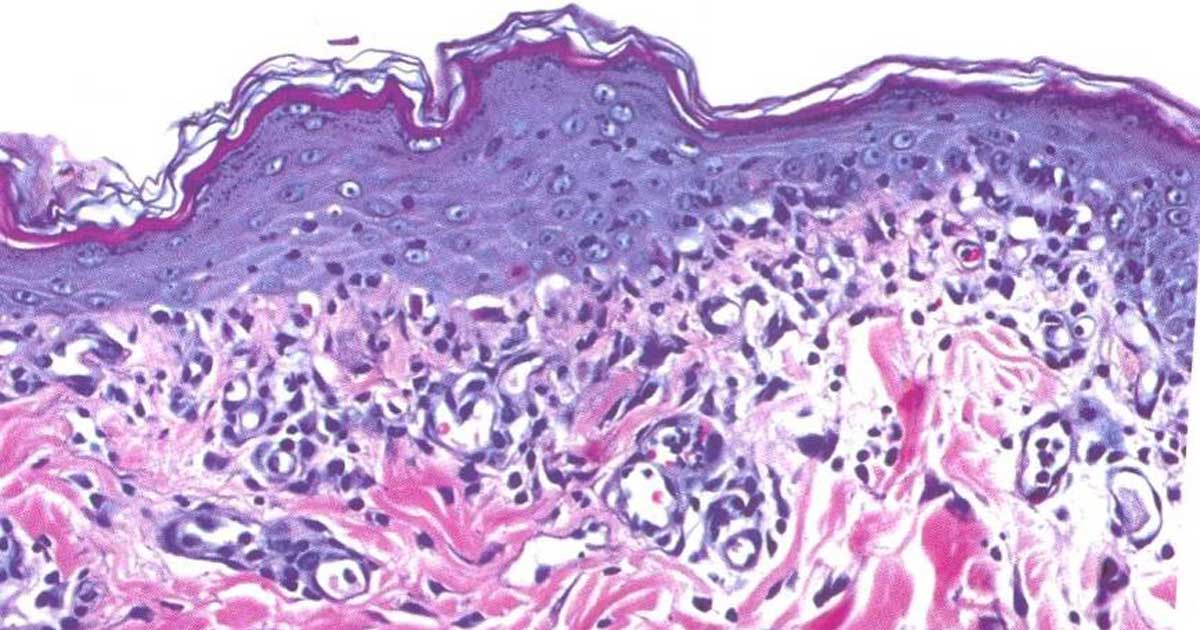

Figure 1. Interface dermatitis. The epidermis is thickened, apoptotic keratinocytes are present and a band of lymphocytes is present in the upper dermis.

The cutaneous variants of lupus erythematosus (CLE) share a common aetiopathogenesis and a similar histopathological picture1. However, the clinical manifestations are very different.

Two groupings exist, comprising the four clinical variants of CLE:

DLE and MCLE are the most commonly found variants in practice. They are both uncommon; however, they have significant differential diagnoses, which means getting a definitive diagnosis is important.

The exact aetiology and pathogenesis of the skin lesions in DLE is not fully understood, but the common factor in all four of these diseases is a lymphocytic attack on basal keratinocytes.

The nature of the antigen driving this lymphocyte attack is not clear. At some point, the immune system is exposed to a nuclear antigen. Some evidence exists that a genetic component may be present in some breeds2 and environmental triggers may occur; for example, actinic radiation3.

Dogs with owners that have systemic lupus erythematosus are more likely to have circulating anti-nuclear antibodies – for example, suggesting exposure to a common environmental factor3,4.

The consequences of the lymphocytic attack are more or less symmetrical erythema, erosion, ulceration, depigmentation and crusting. It is very unusual to see evidence of systemic disease in dogs with a CLE variant. The histopathological findings are characterised by a lymphocyte-rich infiltrate into the upper dermis, a lupoid band, associated with single cell apoptosis – an interface dermatitis (Figure 1).

A lichenoid infiltrate describes a superficial band-like pattern of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the upper dermis. It may be more or less normal underneath a mucosal surface, and may be noted beneath a superficial infection. An interface reaction describes a lichenoid, cell-rich, lymphocytic interface dermatitis, with basal keratinocyte vacuolar degeneration and apoptosis.

A lichenoid infiltrate does not necessarily imply an interface reaction.

The general rules of treating CLE and the variants are to get a definitive diagnosis and try to avoid using systemic treatment – especially long-term prednisolone. Unfortunately, these diseases are chronic and some form of long-term therapy is mandated.

Very recently, Harvey et al5 published a case series of seven dogs with various manifestations of CLE that responded to oclacitinib – albeit at doses of around 1mg/kg once or twice daily.

Patently, oclacitinib has a better side effect profile than prednisolone, ciclosporin and azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil, for example6,7.

What is not clear yet is whether long-term, high-dose treatment with oclacitinib is as safe as long-term treatment at circa 0.5mg/kg once or twice daily.

Currently, the data sheet advises “periodical” blood tests.

VCLE is most commonly seen in the Shetland sheepdog, rough collie and border collie, and their cross-breeds. Around 30 cases have been reported1. In one report of 25 cases, 11 were Shetland sheepdogs, 7 were rough collies and 7 were collie cross-breeds.

The disease was initially termed idiopathic ulcerative dermatosis of the Shetland sheepdog and collie.

Clinical signs are confined to the glabrous skin of the axillae, ventrum and groins (Figure 2). Typical signs are transient flaccid vesicle followed by sharp edged cyclic, polycyclic, and serpiginous erythematous erosions and ulceration. Occasionally, dogs may have mucocutaneous lesions. Secondary infection may be significant. Systemic signs are not seen.

Differential diagnoses include erosive superficial pyoderma and erythema multiforme.

Case management involves general anaesthesia (GA) biopsy. When compared to other forms of cutaneous lupus, many more apoptotic keratinocytes1 are present, sufficient to cause intra-basal clefting – hence the flaccid vesicles.

Systemic medication is mandated. Lesions are aggravated by sunlight, so avoidance is indicated:

Two types of DLE are recognised: the familiar facial-predominant and a much rarer generalised variant.

Classic, facial-predominant DLE is by far the most common variant (Figure 3). The German shepherd dog and its cross-breeds are predisposed. Median age at presentation is seven years, but it has been reported in dogs between 1 and 12 years old.

The most common signs are loss of pigment, ulceration and crusting on the nasal planum and nares – ultimately with loss of architecture. The immediate adjacent skin of the rostral nose may also be affected. The medial canthi, lips (not the mucosae) and the pinnae are affected less often. Lesions scar as they resolve.

Differential diagnoses include:

Generalised DLE (GDLE) is very rare1. To date, fewer than 20 cases have been reported, and none were German shepherd dogs. The affected dogs exhibit lesions primarily on the lateral and dorsal trunk, but head and the perigenital areas may be affected. Multifocal, annular to polycyclic plaques with follicular plugging, pigmentary changes, scale and, less often, crust and ulceration have been reported. The plaque lesions may ulcerate and subsequently heal with a central, atrophic scar.

Differential diagnoses include:

Case management involves GA biopsy. Planum nasale is best biopsied using a 2mm punch. No way exists to obtain a cross-margin biopsy with such a tiny punch, so take two or three samples. The closure is easy-tissue glue or a simple 2-0 polyglactin 910 suture. Take care to use ophthalmic forceps and scissors as the samples are tiny, and you must avoid crushing them.

Try to avoid long-term systemic treatment with high doses of prednisolone for what may be local lesions on the nasal planum and, perhaps, the immediately adjacent face.

An initial short course may be indicated to suppress the inflammatory process sufficient for less potent medications to maintain remission:

Around half of the 30 or so cases reported have been German shepherd dogs, Belgian shepherd dogs and their cross-breeds1. Females are over-represented by around twice. Median age of onset is six years.

The most common clinical presentation is perineal, perigenital and vulval ulceration, accompanied by – at times – frenetic licking (Figure 4a).

Occasionally, the lips and rostral face are affected by chronic cheilitis (Figure 4b).

Note, the oral mucous membranes are not affected, unlike in mucous membrane pemphigoid. The lesions heal without scarring, unlike the lesions of DLE and GDLE. They do not appear to be pruritic, but pain on urination or defecation may be present.

Differential diagnoses include:

Case management involves careful observation and examination, which will enable the diagnosis of perianal fistula. GA biopsy is indicated for the other differentials.

MCLE appears to respond rapidly to treatment – within four weeks in many cases; although, of course, this is not a cure and the owner must be cautioned that treatment must be continued:

German short-haired pointers and Hungarian vizslas – which share ancestry with German short-haired pointers – are predisposed.

In German short-haired pointers, an autosomal recessive genetic error has been found in chromosome CFA 182. The chromosomal error results in abnormal functioning of the gene UNC93B1, which encodes protein “unc-93 homolog B1 TLR signalling regulator”. The abnormality results in an error in handling endogenous DNA, precipitating anti-self-DNA antibody production.

In the largest case study, of 25 cases, clinical signs of scale and alopecia were the most common. In total, 25% of dogs had follicular casts. Some present with irregular, polycyclic patches and plaques and depigmentation on the muzzle, pinnae and trunk, or with generalised lesions. Pruritus has been reported in 30% of cases.

Unusually, for a DLE variant, the age of onset is late juvenile, early adult, with a mean age of onset around eight months.

ECLE in the Hungarian vizsla was originally misidentified – at least in some dogs – as granulomatous sebaceous adenitis1. A loss of sebaceous glands is a feature of around 50% of ECLE cases. An inflammatory exudate is present around the sebaceous glands, but in addition, a cell-rich interface dermatitis and apoptic keratinocytes are also present, and a moderate to marked lymphocyte exocytosis into the epidermis.

Clinically, the dogs exhibit multifocal, often coalescing patches of alopecia, but scarring is visible (Figure 5). Follicular casts and scale, just as in the German short-haired pointer, are also present. In addition, some have polylymphadenopathy.

Both the Hungarian vizsla and German short-haired pointer may develop arthralgia, manifesting as a stiff gait and hunched back.

Diagnosis is based on histopathological features of a lichenoid band and interface dermatitis, often hyperkeratosis, apoptosis in the upper epidermis accompanied by exocytosis of lymphocytes. Inflammation is present around the follicles and, in many cases, the sebaceous glands are absent.

This DLE variant is accepted as the most challenging to treat. Some 50% cases are euthanised because of a failure of any treatment to ameliorate the clinical signs.

Cases fail to respond to either single treatment, or combinations of, OTC/niacinamide, azathioprine, ciclosporin or high doses of prednisolone1. Oclacitinib 1mg/kg twice daily was shown to be very effective5, giving veterinary surgeons a valuable option in managing these difficult cases.