30 Aug 2022

Most clinicians will quite rightly presume that a digestive tract ailment is responsible for signs of regurgitation in dogs.

Occasionally, however, these signs can be caused by partial extraluminal compression of the digestive tract.

Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of a vascular ring anomaly compressing the thoracic oesophagus, thereby causing signs of regurgitation in young dogs.

During development of the embryo, major blood vessels are derived from a series of paired dorsal and ventral aortas.

Each aorta is connected to its pair via six aortic arches. The heart and the great vessels, and what we recognise as “normal” vascular anatomy, forms from selective fusion of some of these primitive vessels and the simultaneous involution of others.

The aorta usually develops from the left ventral aortic root of the fourth arch and the left fourth aortic arch, while the brachiocephalic trunk and right subclavian arteries form from the right-sided equivalents.

The aorta, therefore, normally forms on the left side of the chest. The ductus arteriosus that connects the aorta to the pulmonary artery should start to close within a few days of birth and this goes on to form a ligament (the ligamentum arteriosum).

Vascular ring anomalies (VRAs) arise from erroneous vascular development. Numerous abnormal vascular patterns are possible and many will go unnoticed as long as they do not cause clinical signs of disease.

The most common clinical VRA is a “persistent right aortic arch” (PRAA). In this scenario, the aorta forms from the right aortic arch rather than the left.

Although this in itself is of no consequence in terms of blood delivery, the ligamentum arteriosum now traverses the oesophagus, which has to now run between the aorta and pulmonary artery.

Animals with PRAA, therefore, tend to present with signs of oesophageal obstruction.

Pups with PRAA usually start off well as the oesophageal constriction is not complete and will allow fluid (milk) to pass unhindered to the stomach.

Signs of regurgitation classically start when affected dogs are weaned, with the majority of cases developing clinical signs between two and six months of age.

The oesophagus starts to dilate cranially to the obstruction and so regurgitation can start several minutes after eating, as food can lodge in the oesophageal pouch that starts to form.

Animals start to lag behind littermates and can appear malnourished, despite usually having a very good appetite.

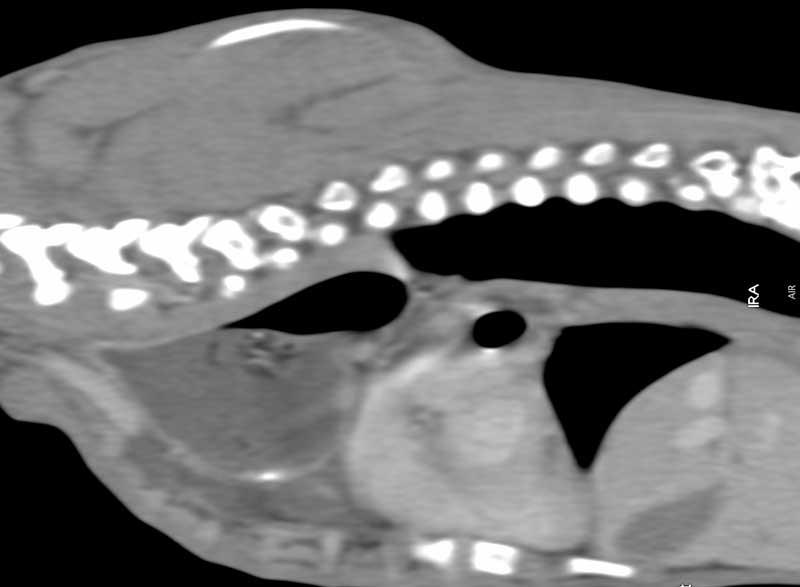

Clinical signs and signalment alone can be very suggestive of VRA. Plain radiographs will show oesophageal dilation proximal to the heart base.

Dorsoventral views may also show a focal deviation of the trachea to the left and/or the descending aorta on the right in cases of PRAA.

Contrast series (barium) can also be performed to better define the point of oesophageal constriction.

Advanced imaging (for example, CT) can also be used to confirm the vascular malformation.

Lung fields should be screened for evidence of aspiration pneumonia whichever thoracic imaging modality is used.

Medical management is limited to feeding dogs soft/liquid food from a height. Dogs can be held in a “meerkat” pose after eating to help gravity assist the transit of ingesta down into the stomach.

Any aspiration pneumonia needs to be resolved prior to surgery and a gastrotomy/PEG tube is occasionally required to provide nutrition to the animal if deemed to be very under-nourished, and surgery, therefore, has to be delayed.

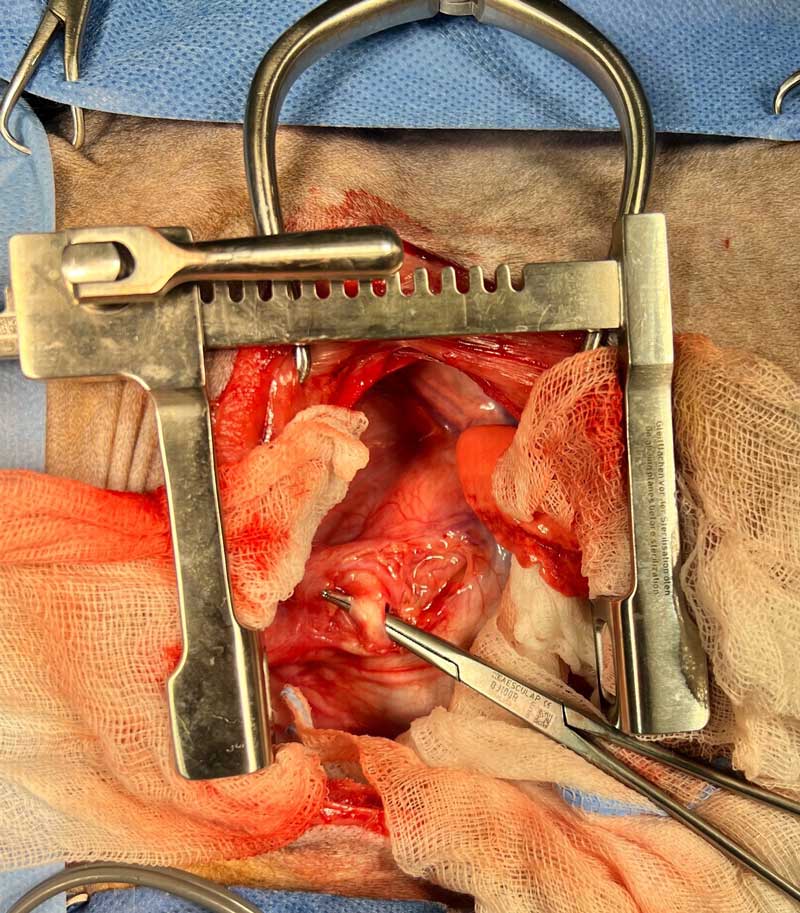

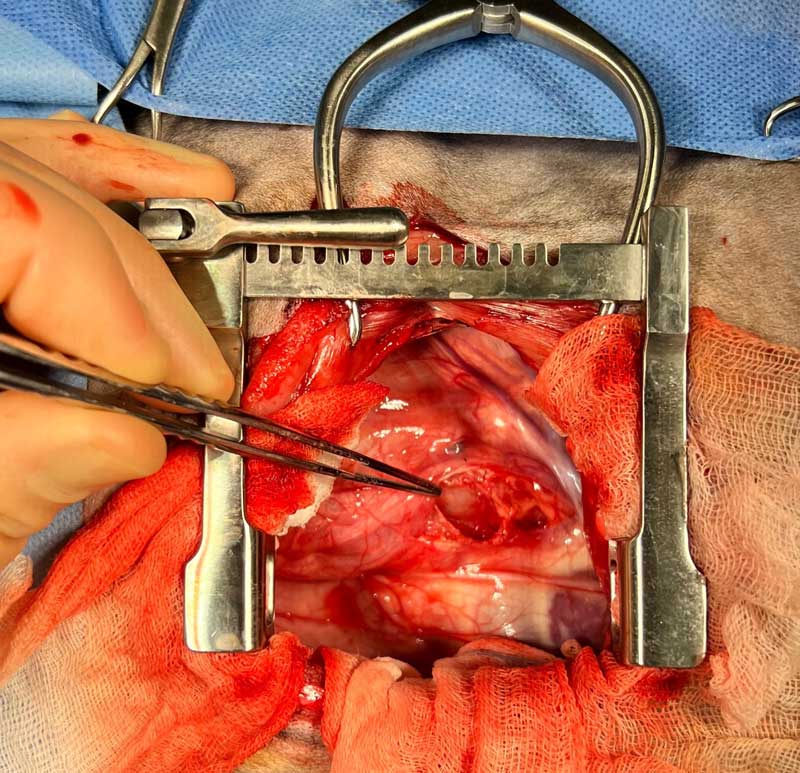

Surgery is the recommended treatment for PRAA. The ligamentum arteriosum needs to be ligated (in case it is patent) and transected to release the oesophageal compression.

The surgical approach for PRAA is, therefore, the same as for a patent ductus arteriosus – a left fourth intercostal thoracotomy.

A wide-bore stomach tube is usually advanced along the oesophagus to help release any residual constrictive bands of fibrous/scar tissue.

Other VRAs may also be present – for example, an aberrant left subclavian could potentially cause a second, more cranial obstruction and so a good knowledge of vascular anatomy is essential for a good outcome.

Dogs usually recover very well from this surgical approach. Dogs are continued to be fed liquid food from a height in the early stages of recovery.

The consistency of food fed can then be gradually changed over two to four weeks – the fluid content is gradually reduced and then, if the dog is doing well, feeding from lower heights/ground level can be attempted. Although many dogs will go on to do very well, a risk exists of residual oesophageal dysfunction and so many dogs will require ongoing dietary control.

Multiple studies have been produced quoting different success rates, but it seems that approximately 80% to 90% of dogs are judged to have had very good/excellent outcomes by their owners.

The likelihood of postoperative oesophageal dysfunction and the need for ongoing modified feeding regime may be related to the duration of symptoms preoperatively (and, therefore, related to the degree of preoperative oesophageal dilation that develops).

Surgical intervention is, therefore, usually performed as soon as the patient is judged to be safe and able to undergo thoracotomy.