2 Feb 2025

Matt Gurney BVSc, CertVA, PgCertVBM, DipECVAA, MRCVS considers treatment options, including analgesics, for this disease usually seen in older pets.

Image: Elina Volkova / Adobe Stock

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a disease of older pets, right? It is a commonly held belief, but new research has shone a light on OA in young dogs.

This has the potential to change how we should be diagnosing, monitoring and managing this common condition.

In a study published in 2024, Enomoto and colleagues recruited a mixed population of dogs aged between eight months and four years of age to assess for OA – the first time this has been done in a young population of dogs.

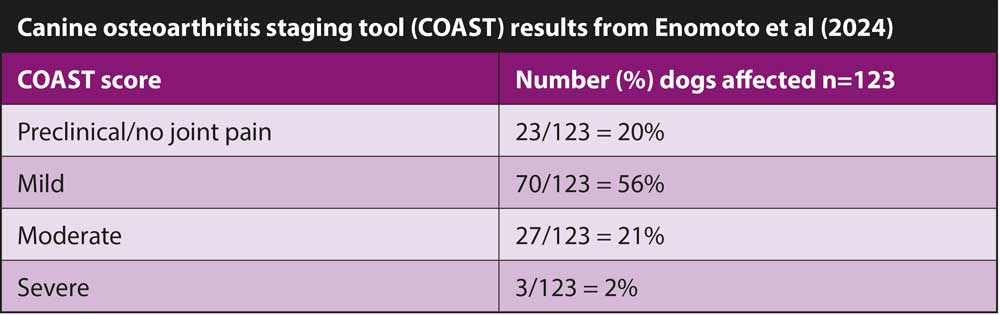

Each dog was examined by a veterinarian and then underwent radiography. During the examination, the investigators were looking for lameness and evidence of pain on joint manipulation. Clinical OA (cOA) was defined as an overlap of radiographic OA (rOA) and joint pain in one or more joints. Each caregiver was asked to complete an OA questionnaire and this, coupled with the veterinary and radiographic examination, led to a canine OA staging tool (COAST) score being assigned to each dog.

The COAST score is useful, as it allows the progress of a dog’s OA status to be tracked over time. The output from the score gives a grade from preclinical, mild, moderate and severe. This is also helpful for the caregiver to understand how affected their dog is. With further research, it may be possible to make treatment recommendations based on specific scoring results.

Estimates as to the prevalence of OA in the general canine population varies between 20% to 40%. In this young population of dogs, the prevalence of cOA with mild pain was 23.6%, and with moderate pain 16.3%.

The most represented breed was mixed breed (32 out of 123), followed by the Labrador retriever (12 out of 123). The most commonly affected joints were the elbow, hip, tarsus and stifle (in that order). Dogs demonstrating rOA were more likely to be at the higher end of the age range, be heavier in bodyweight and have a higher body condition score. Dogs with cOA were also more likely to be at the higher end of the age range.

In this population of young dogs, the prevalence of rOA and cOA with mild pain was 23.6%. The same diagnostic criteria with moderate pain was 16.3%. These figures demonstrate that OA should firmly be on the list of things to look out for in younger dogs.

The earlier OA is recognised, the sooner intervention can happen. All too often, we see OA cases too late, when the disease has progressed, management is more challenging and the dog has been experiencing pain for some time.

One thing the outlined study highlighted is that despite a high incidence of OA, only a very small number of the dogs were being treated for pain. This may be reflective of the fact that caregivers are not necessarily recognising pain in their dog.

In the study, owners did not notice any outward signs of OA in their dog until an average of 28 months of age. This increases the importance of us, as vets, being more vigilant and proactive.

Another thing that the study revealed is that COAST scores appear to increase mainly due to the presence of multiple joints being affected in addition to worsening of the actual OA scores. This highlights the importance of early treatment and close monitoring of all joints once OA is recognised in one joint.

Although early identification of OA is clearly beneficial to the patient, it is not without its challenges.

The authors of this work commented that attempts to measure OA pain in young dogs using the metrics they employed may be fundamentally flawed because these instruments were developed in older dog populations. The same applies to existing tools such as the Canine Brief Pain Inventory and the Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs questionnaire, which are designed for dogs already experiencing mobility-related diseases.

A different approach is, therefore, likely required for detecting subtle, early-stage changes in mobility that occur in younger dogs.

This gap in understanding has been addressed in a recent publication by Clark et al (2023). A tool, called the GenPup-M questionnaire, is the first of its kind to be tested in healthy dogs, starting from as young as five months old.

The objective is to allow earlier detection of mobility-related issues and enhance preventive care in dogs. It is a validated, caregiver-reported tool that can be used throughout a dog’s life at annual intervals. Incorporating such methods into health care plans brings value to our clients and enables us to help as many pets as possible.

These and other tools will no doubt further develop and improve over time; a collaboration between the University of Liverpool and Dogs Trust is already underway to facilitate the development of GenPup-M into an open-access smartphone app for owners to use.

An important first step, though, is shifting the general veterinary mindset that OA is found in older dogs only. Given that the median age at first diagnosis of OA was 10.5 years in dogs attending UK primary care veterinary practices (O’Neill et al, 2014), it is clear that our focus needs to shift. Active screening of younger dogs for OA is recommended, and although the outcome of this proactive approach has not been assessed, logic dictates that the benefits would be significant.

Recognising OA early in younger dogs provides more opportunities to fully reap the benefits of OA management strategies other than conventional NSAIDs.

This is even more pertinent, with some owners and vets understandably concerned about the adverse long-term effects of using NSAIDs in younger dogs.

A recent systematic review into nutraceuticals supported supplements containing omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment of OA (Barbeau-Grégoire et al, 2022). Further work into a compound derived from green-lipped mussels, EAB-277, has shown promising results (Kampa et al, 2024) when compared to meloxicam, placebo, and another supplement. Over six weeks, dogs in the EAB-277 group demonstrated significant improvements in limb function with reduced pain that was comparable to the NSAID group.

A further trial (Kampa et al, 2023) showed meaningful improvements in peak vertical force and caregiver-reported pain scores after two and four weeks of treatment.

With moderate and severe OA, once cartilage integrity is compromised, the success of regenerative options such as stem cells (Beerts et al, 2023) and platelet-rich plasma (Alves, et al, 2021) decreases. Early diagnosis in younger dogs provides more opportunity to use these options to their maximal benefit.

The work described by Enomoto and colleagues (2024) recognises that body mass is a risk factor for OA in younger dogs and, therefore, must form a key pillar of management.

Assessment by a veterinary physiotherapist will enable the caregiver to understand how to manage their dog’s exercise to promote mobility and maintain optimal body condition.

Monitoring pain is important in these cases: at some point, the OA will progress and conventional analgesics will be required. If any doubt exists as to the existence of pain, a pain trial is recommended.

The licensed, first-line treatment options for OA in dogs are NSAIDs, bedinvetmab (dogs older than one year of age) and grapiprant. Any of these options are also suitable for a pain trial.

OA is a progressive disease. So, at some point, the pain that was previously controlled by first-line analgesics will progress and require additional analgesia. Alternatively, some severe cases may not be adequately controlled by first-line options from the outset and require adjunct analgesics.

The pain pathophysiology of OA is inflammatory. Our first-line analgesics act in the periphery to control the inflammation and its impact on higher centres. Once arthritis pain is established or becomes more severe, changes occur in the central nervous system and, in addition to peripheral sensitisation, centralised pain develops.

Second-line analgesics attempt to address the processes that occur to produce centralised pain. Examples would be the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists such as amantadine, memantine and ketamine, which target the NMDA receptor, a key receptor involved in central sensitisation.

Tracking the progression of OA is really important to identify when additional analgesics are required. The use of clinical metrology instruments is recommended from first presentation to assess the impact of the OA on the dog. Examples of these include the Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs score, the Helsinki Chronic Pain Index or the Canine Brief Pain Inventory.