5 Feb 2025

Laura Edwards BA, RVN, TOFE, AFHEA, CertVNECC and Karin Gerber RN, BSc, MSc explain this cross-professional strategy which addresses global issues in human/animal health.

The one health approach is a collaborative strategy that considers the health of people, animals and the environment to be interdependent, and aims to improve global health (WHO, 2017).

It can be applied in both veterinary and human health care to help us address global health issues that affect patients, family members and the planet.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for a global framework for improved surveillance and a more holistic, integrated system. Gaps in one health knowledge, prevention and an integrated approach were seen as key drivers of the pandemic.

By addressing these gaps between human, animal and our overall environmental health, one health is seen as a transformative approach.

One of the first questions we want to address is, why? Why should animal-centred and human-centred nurses collaborate? Looking at these images, our daily working lives are not so different. Which of these are veterinary centred and which are human centred?

The aim is to do more than talk; the dream is integrated health and welfare research. Why work together? What are the benefits?

Pet owners have high expectations of survival rates in their pets: Corr et al (2024) found that nearly 60% of pet owners believed that their pets should have access to the same diagnostic tests as their owners.

It could also be further argued that due to the astounding work being done in human medicine, pet owners’ personal experiences of treatments are informing their choices of treatments of their pets.

Or, is the drive towards more complex veterinary treatments more closely aligned to the increasingly reliant relationship pet owners have with their animals and the decrease in availability of human-centred community social care? We can see from the Care Quality Commission (2023) data that the increase in demand between 2023 and 2024 for mental health services in England rose by 21%, but the number of interactions with the service only rose 9%. The statistics are worse in children and young people.

The PDSA Animal Wellbeing (PAW) Report (2024) reported that 51% of the UK population own a pet, including 10.6 million pet dogs, 10.8 million pet cats and 800,000 rabbits. If we are to look at the population of humans, that means roughly one in every three humans in the UK owns a pet.

These numbers did not even look at the many other animals that humans decide to share their lives with. A total of 91% of pet owners felt that their pet improved their life, with 88% reporting the pet makes them mentally healthier, and 69% of owners stated their pet improves their physical health. Martins et al (2023) suggested that pet owners may have higher levels of social support, life satisfaction, happiness and mood with lower levels of loneliness than non-pet owners.

From as far back as the 1970s, research has long pointed towards the positive health benefits of owning a pet (Mencke, 2024).

Animal-assisted interventions (AAI) are increasingly used as a complementary therapy in clinical settings. The International Association of Human-Animal Organisations define AAI as “a goal oriented and structured intervention that intentionally includes or incorporates animals in health, education and human services (for example, social work) for the purpose of therapeutic gains in humans” (Jegatheesan et al, 2018).

Westgarth et al (2019) found that people who own dogs are four times more likely to meet current physical activity guidelines than those non-dog owners, and in a study of adults older than 50 years with mildly elevated blood pressure, the presence of a pet dog or cat had a significant impact on blood pressure, with cat ownership being associated with lower diastolic and systolic blood pressure (Surma et al, 2022).

In a study exploring if AAI improves pain perception in polymedicated geriatric patients with chronic joint pain (Rodrigo-Claverol et al, 2019), patients reported reduced pain, discomfort, and stress; additionally, stress among nursing staff was found to decrease significantly following AAT sessions. Pets were found to contribute to a stronger sense of identity in owners with mental health conditions, including reducing negative perceptions of a condition or diagnosis.

Pets provide a sense of security and routine in the relationship, which reinforces stable cognition (Martins et al, 2023). Dogs and cats play an integral part in the rehabilitation and mobilisation of humans; more than 7,000 people rely on an assistance dog for a range of conditions (Assistance Dogs UK).

The question is: “How can human nursing embrace the health benefits of pet ownership to drive recovery, rehabilitation and, ultimately, reduce the numbers of people being admitted to hospital, and what can veterinary staff do to lead the conversation?”

Part of that answer must include the two disciplines talking to each other, exploring different avenues of collaboration that might include getting help understanding the dynamic between your patient and their pet at home. How can you use that relationship to a positive end? Understanding the connection between unhealthy lifestyles and the survival outcomes of pets (Plante et al, 2023).

The human-animal bond between a person and their pet can be so strong that those experiencing homelessness may often forego services and/or food for themselves to provide for their beloved pet. One health clinics are a unique interdisciplinary way to provide health care to both the human and their companion pet as one family unit. Health care is provided to each individual alongside examining the intersectionality, which can include zoonotic diseases, nutritional issues and mental health to name a few.

The gold standard of care for a true one health clinic is to be a fully integrated clinic where both people and pets have access to primary health care at one place and at one time, where both the human and veterinary health care providers create a joint health care plan (Sweeney et al, 2018).

The bond we share with our pets is important for many; unfortunately, this is often exploited in violent and or abusive relationships, where it is used to gain power and control over the person and or family members. This can range from threatening to harm the pet, to stopping someone being able to care for their companion pet in the way they want to.

Staff in human-centred hospitals and veterinary practices should both be able to signpost cases of domestic abuse to charities that will help with their pets at home. Studies have confirmed that in households with companion animals experiencing domestic violence and abuse, a high probability of animal abuse exists.

The National Link Coalition is an organisation working to increase awareness of the connection between animal cruelties and domestic and community violence, and they have highlighted that:

Those in these circumstances are often unaware of the various programmes available to assist families with companion animals by providing pet care when an individual needs to escape quickly. Many animal welfare agencies provide emergency accommodation. Many refuges can in certain circumstances accommodate the animal, but these needs expanding. Children especially often rely on their pet to provide stability, security and companionship.

Can we work together to ensure families, and their pets stay together at a time of need? The human-animal bond is a mutually beneficial relationship between human and animal. The key is the word “mutual”, which means we must have the animals’ needs considered alongside the humans. Veterinary practice does not just treat animals. We have a unique window into the human-animal bond in action. We counsel, listen and work with humans, taking into consideration medical needs and barriers, finances and well-being. It is impossible to just treat the pet.

We manage expectation and hope, and consider the unique role the pets play in the owners’ life, as well as dealing with the owners’ own personal experience with health care. These are just a few of the considerations we must put forward when deciding on treatments.

With the increase in pet ownership and the reliance on pets for companionship, healthy lifestyles and a myriad of other reasons, the conversation between human and veterinary medical care has never been more critical.

A particular discipline of veterinary and human care that shares many treatments and research is critical care. Human and veterinary emergency and critical care share attitudes and values, and provide a multitude of opportunities for the development of both professions.

Emergency and critical care management of cats and dogs is similar to that of humans. Veterinary critical care teams have access to advanced diagnostics and imaging, capnography and invasive haemodynamic monitoring. Critically ill animals can require ventilation, interventional radiology, haemodynamic support, transfusions, renal replacement and complex interventional cardiology similar to human patients. Therefore, we believe cooperation between human and veterinary critical care nurses can provide a bidirectional, synergetic pathway that can benefit both.

The BVNA and the British Association of Critical Care Nursing (BACCN) has decided to join forces and create a working group. Our remit is to continue to explore the possibilities of working together for the health and well-being benefits of all our patients.

We aim to discover new ways of working. Learning from the years of expertise and practice from both sides. Veterinary medicine is at the forefront of research looking at how as a planet we can live more harmoniously with animals; how can we avoid the next pandemic; and how can we help humans and pets lead a healthier life?

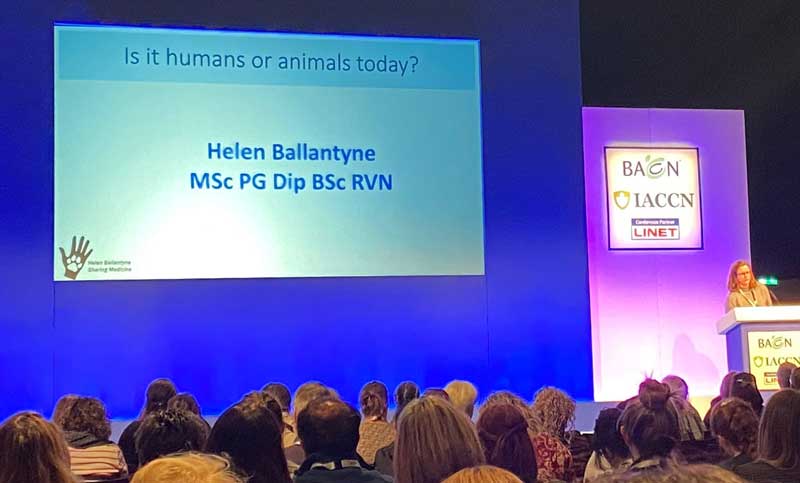

Helen Ballantyne presented on this unique one health collaboration while delivering a keynote session at the first ever joint BACCN and Irish Association of Critical Care Nursing conference in Belfast in 2022.

She later reflected on this and said: “The vision of (this joint work) is to provide a unique collaborative learning experience: the opportunity for VNs to learn from experienced intensive care nurses, who have novel technology at their fingertips, access to advanced, contemporary clinical research and, like their veterinary counterparts, a genuine passion to the do the very best for their patients.

“There (are) plans in place to encourage and provide funding support for critical care VN research, promote evidence-based practice, and design exchange programmes so that ITU nurses might see how a veterinary ITU works, and vice versa. While it is only natural to suggest that most of the learning benefit will be towards the younger, greener veterinary nursing profession, clear benefits exist for human-centred nursing and patient care, too.”

She added: “Consideration of the human-animal bond may make human-centred nurses’ lives a little easier, and maybe even prevent ITU admissions through supportive health promotion.

“Collaboration could support antibiotic stewardship, and clinical research may offer novel treatment options across the species.” (Ballantyne, 2023).

Alongside Helen’s session, other veterinary critical care nurses delivered both oral and poster presentations covering subjects such as tracheostomy and nasogastric tube feeding safety, as well as a session on veterinary euthanasia.

Since then, we worked on a mutual exchange programme enabling observational visits to both a human and veterinary critical care unit, respectively.

We are looking for nurses who would be interested in finding novel ideas and conversations around this topic. Or, if you would just like to find out more with no obligations, contact the Veterinary Critical Care Nursing team via [email protected]

This article appeared in: