9 Jan 2024

Image © SciePro / Adobe Stock

Infections with Giardia duodenalis are common in cats and dogs throughout Europe, with many pets acting as subclinical carriers. This can make it difficult to establish the significance of infection found in patients with diarrhoea. This, alongside potential zoonotic risk, makes decisions about when and how to treat Giardia species difficult.

This article considers the approach to diagnosing and treating clinical cases, the significance of a positive diagnosis in the subclinical pet and control of infection in larger groups of dogs.

Keywords: Giardia species, giardiosis, treatment, control

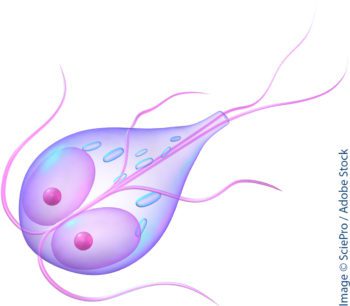

Giardia duodenalis (also known as G intestinalis) is a flagellate protozoan that inhabits the intestines of a variety of domestic and wild animals. Infection can be subclinical and prevalence of infection high (Bouzid et al, 2015). This can make it difficult to establish the significance of infection found in patients with diarrhoea.

With possible Giardia species resistance developing to chemotherapeutic agents (Lalle and Hanevik, 2018), careful consideration should be made as to whether to treat subclinical carriers and how to treat dogs with gastrointestinal (GI) disease.

The life cycle of all Giardia species is direct, with flagellate trophozoites dividing by binary fission in the small intestine and intermittently forming infective cysts that are passed in the faeces.

Transmission occurs by the faecal oral route, with environmental contamination with cysts. Cysts can be long lived in the environment – especially in cool, damp conditions – and may be present in the coats of infected animals where faecal contamination has occurred.

Many species of Giardia are species specific, but G duodenalis can infect a wide variety of mammals, including humans, cats and dogs. G duodenalis is commonly split into eight sub-groups or assemblages, with each assemblage infecting one or more host species in immunocompetent hosts. The dog and cat assemblages are relatively species specific; this means dogs are unlikely to infect cats and vice versa if living together in households, and pose very little zoonotic risk. The exception is if people are already infected from other sources.

Infection in humans is with assemblages A and B, which can potentially also infect cats and dogs if they are exposed to environmental contamination from human infection (Cacciò et al, 2005). This means human infection can be cycled through pets, allowing transmission to other people.

People infected with Giardia species who work with domestic animals also pose a high risk of passing on infection. Animals infected by the person may then remain a reservoir of zoonotic infection. Veterinary professionals infected with the parasite should, therefore, be isolated from pets at work until the infection has cleared. Infected people should also maintain strict hygiene with their own pets, and avoid contact with other cats and dogs if possible until infection has been resolved.

Many cases of Giardia species infection in hosts with a healthy GI system are subclinical. Infection, however, may cause GI disturbances or contribute to existing GI disease. No pathognomonic clinical signs are associated with infection, with the most common sign being chronic, sometimes intermittent small bowel diarrhoea. This can be mucoid, foul smelling and accompanied by flatulence. Lethargy and weight loss may also develop in the face of a good appetite.

Less commonly, large bowel involvement with tenesmus may occur. Clinical disease is most likely to occur in young animals and in the immunosuppressed. The clinical picture can also be further complicated by concurrent GI disease and infection.

Puppies with diarrhoea will often have mixed infections of Giardia, Campylobacter and Cystoisospora species. The prognosis is good in most clinical cases, but young, debilitated, geriatric or immunocompromised animals are more likely to be severely or chronically affected.

The non-specific nature of the clinical signs of giardiosis means that Giardia should be considered as a differential in the investigation of all diarrhoea cases in dogs. It should not, though, be assumed to be the sole cause of GI disease if diagnosed.

The following methods are all useful in the diagnosis of Giardia species infection.

Flotation techniques tend to underestimate clinical infection and, in contrast, antigen and PCR testing overestimate them.

Flotation used in combination with one of these other tests is, therefore, extremely useful to confirm if infection is present or persisting after treatment, and the degree of cyst shedding that is taking place.

Flotation used in combination with one of these other tests is, therefore, extremely useful to confirm if infection is present or persisting after treatment, and the degree of cyst shedding that is taking place.

Diagnostic testing should be repeated in animals after treatment to see if shedding is still taking place, and where clinical signs have not improved to establish if infection has been eliminated. This should be done no more than three days after the completion of treatment to establish if infection is persisting, rather than infection having reoccurred from the contaminated environment. This is important, as many multi-pet and individual infections prove difficult to clear because of insufficient environmental hygiene, rather than lack of treatment efficacy.

The Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC) recommends performing a faecal flotation with centrifugation primarily for detection of cysts after treatment, rather than faecal antigen tests alone. This is because faecal antigen tests may remain positive even after treatment for variable periods of time, even if infection has resolved.

If Giardia species cannot be detected, but clinical signs persist, further diagnostic procedures should be carried out for other causes of the presenting clinical signs.

Common compounding factors for diarrhoea in Giardia species-positive dogs include concurrent protozoal infections such as Cystoisospora species, bacterial infections such as Campylobacter species, chronic inflammatory bowel diseases and food allergies.

In clinical cases of giardiosis, a number of different drugs have been shown to have some efficacy.

A low-residue, highly digestible diet may help to reduce diarrhoea during treatment. The diet should also be low in carbohydrates and high in protein, to inhibit excessive growth and replication of Giardia and Clostridium species.

A low-residue, highly digestible diet may help to reduce diarrhoea during treatment. The diet should also be low in carbohydrates and high in protein, to inhibit excessive growth and replication of Giardia and Clostridium species.

Reinfection from environmental contamination is common, and good environmental hygiene is essential to prevent this.

Pets should be regularly cleaned to remove faecal contamination from the coat and clipped to reduce the risk of contamination building up. This is especially important in long-haired breeds and around the perineum, where soiling is common.

Faeces should be picked up and disposed of responsibly daily, and pet bedding hot washed to at least 60°C.

Treatment is not advised for subclinical carriers of Giardia species, as infection is common, zoonotic risk very low and the potential exists for drug resistance to develop. Therefore, it is not recommended to screen pets for Giardia species as routine practice, as subclinical infection is of little significance. An exception to this is when the aim of treatment is to eliminate the parasite from multi-pet households with recurrent clinical infections, breeding or kennel establishments.

Screening may also be of benefit if severely immunocompromised people are in regular contact with the pet. Here, PCR will potentially be of benefit if zoonotic infections can be distinguished from those that pose no risk. If subclinical dogs are identified either through screening or after a clinical episode, then clients should be advised of potential zoonotic risk, but also that this will generally be very low.

Good hand hygiene and hygienic disposal of the pet’s faeces should also be advised.

The potential for clinical outbreaks makes the control and prevention of spread of Giardia species desirable in kennels, breeding establishments and domestic situations where clinical outbreaks keep occurring in multi-pet households.

A number of steps are required to achieve this.

Discussions should be had with the client before elimination strategies are initiated. Success requires good compliance, areas where pets can be isolated and environments where large areas can be cleaned/hot washed with disinfectants.

This may not be practical in some household situations, and a labour-intensive prolonged elimination programme may be something that some pet owners do not want to undertake.

Without these steps, however, clinical infections in multi-pet households are likely to be recurrent – especially in those with large numbers of young or sick animals.

Giardia species infections are common and, although many cases in dogs are subclinical, they can lead to significant GI signs. Treatment with chemotherapeutic agents is useful for reducing clinical signs, but infection is difficult to eliminate.

Overall zoonotic risk is low, and so, little justification exists in treating subclinical carriers unless the aim is to protect the severely immunocompromised, or to eliminate infection from premises where clinical outbreaks keep occurring. Whether clinical infection is being controlled in an individual pet or a group, hygiene plays a key role in reducing environmental contamination and subsequent infection levels.

Consideration of Giardia species as a differential in diarrhoea cases, and early diagnosis using a combination of techniques, will help to control outbreaks and improve treatment outcomes.