3 Nov 2021

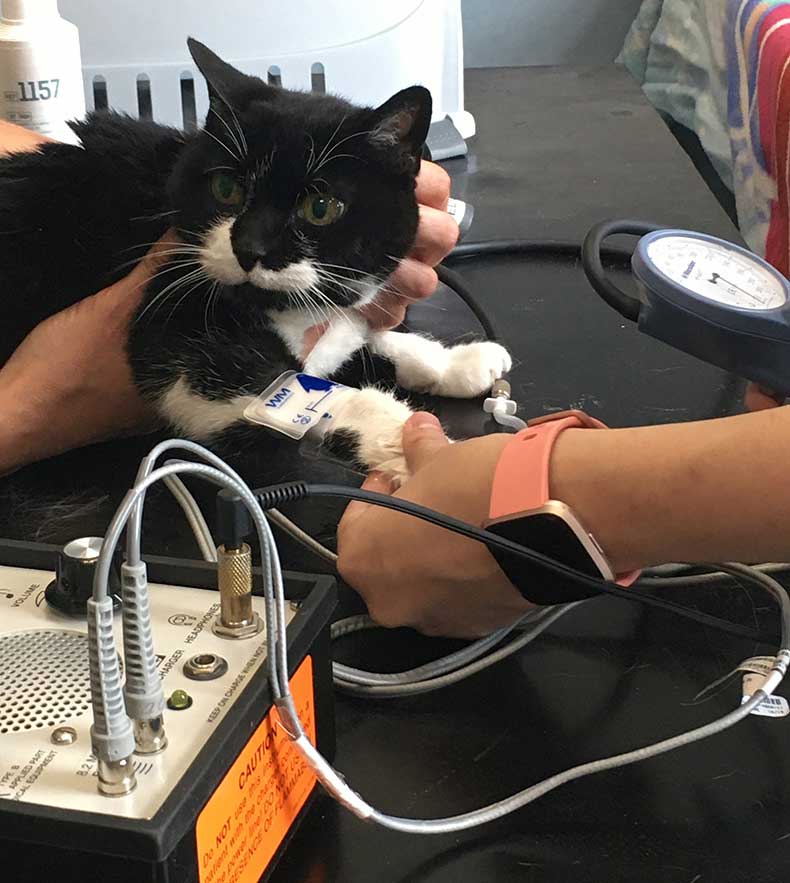

Figure 1. Cuff measurement.

Systemic hypertension is well recognised as a significant cause of morbidity in older cats. Early outward signs can be subtle or absent.

In most cases, hypertension is not a primary disease process, and discovering high blood pressure (BP) is just the beginning of a diagnostic process.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), hyperthyroidism and primary hyperaldosteronism are the most common causes of hypertension in cats. BP assessment is mandatory in any cat in which one of these conditions has been diagnosed, and, conversely, where systemic hypertension is identified in an elderly patient, these are the conditions for which screening should subsequently take place.

Essential hypertension – a term used when no underlying cause is found – is sometimes applied to cats. However, a major mechanism for this disease in humans is hyalinisation of the peripheral vasculature, such that adaptations to vascular tone cannot occur, and this process has not been identified in cats and dogs.

In veterinary species, the term “idiopathic hypertension” is therefore preferred, given as yet it remains unclear whether hypertension really can be a primary occurrence, or whether other occult disease, such as early renal or adrenal dysfunction, might be responsible in every case.

Potentially also worth consideration is a variety of other conditions that are either less common and/or have a less well-established association with systemic hypertension, such as diabetes mellitus or hypersomatotropism – even phaeochromocytoma or hyperadrenocorticism (both rare).

Systemic hypertension has the potential to damage some or all of the brain, eye, heart and kidney. Which target organ is affected, and to what degree, depends a little on the individual situation, particularly the speed of development of hypertension.

For example, rapidly progressive marked hypertension could lead to seizure activity or sudden blindness due to retinal detachment, whereas if high BP develops gradually over time, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) may be marked, whereas the brain would have the chance to adapt such that neurological signs would be absent.

Hypertension-induced LVH can be reversible once hypertension is controlled. However, it is important to recognise the potential for its presence prior to treatment as affected patients are at greater risk of volume overload – particularly secondary to fluid therapy.

Proteinuria is an indicator of all-cause mortality in cats, and it is a prognostic indicator in CKD. It is considered likely that it is also a mediator of CKD progression in cats, as it is in man and dogs. The development of proteinuria is related both to systemic hypertension and to intraglomerular pressures; both can be addressed medically.

Indirect BP measurement can be achieved with either a Doppler or an oscillometric device. Despite the introduction of partially validated high-definition oscillometric devices to the market, Doppler methods are still preferred in conscious cats and when correctly applied, the readings they generate are accepted as a reliable indication of true systolic blood pressure (Haberman et al, 2004; Jepson et al, 2005; Acierno et al, 2018).

The technique takes some practice, but clear step-wise instructions are available (Panel 1).

Popular sites for obtaining BP measurement in the cat are the coccygeal artery, on the underside of the tail or the common digital artery of the forelimb (between the carpal and metacarpal pads).

Situational hypertension – a temporary, spontaneously reversible state caused by anxiety or stress – is commonly encountered and can be differentiated from true hypertension by careful attention to BP measurement technique, repeat measurements over a day or on more than one occasion and examination for target organ damage.

Fundic examination facilitates detection of early ocular changes secondary to hypertension, including segmental constriction of the retinal vessels, and more advanced pathology such as retinal oedema, haemorrhage and detachment (Figure 2).

Assessment of haematology, serum biochemistry (including renal parameters, glucose, electrolytes and phosphate levels), total thyroxine (+/− thyroid-stimulating hormone and free thyroxine in difficult cases), along with urine specific gravity, sediment examination and protein:creatinine ratio, provides a good starting point for investigation of a cause of hypertension.

Systemic hypertension is a common finding in cats with CKD and the ongoing risk of development of systemic hypertension is strongly correlated with the presence of CKD (Bijsmans et al, 2015). BP assessment is indicated in all cats with CKD, both at the time of diagnosis and also subsequently, even if the initial readings are not abnormal.

A strong association also exists between hypertension and hyperthyroidism in cats, even though a convincing mechanism, and solid cause and effect relationship, have not been well established.

Hyperthyroidism can significantly affect the renal and cardiovascular systems due to an increase in circulating catecholamines and metabolic rate, and a resultant increase in cardiac output. Restoration of a euthyroid state generally improves the cardiovascular status, but ongoing BP assessment is prudent.

An early study (Kobayashi et al, 1990) showed that 87% of hyperthyroid cats were hypertensive, but that adequate control of the hyperthyroidism also controlled the hypertension, as far as follow-up was maintained (four months).

In contrast, a more recent study found that a little more than 20% of initially normotensive hyperthyroid cats went on to develop hypertension despite good control of hyperthyroidism over a six-month period (Syme and Elliot, 2003).

The cause of this (for example whether it was related to the appearance of CKD) was not always clear, but it does highlight that suspicion for the development of hypertension should be maintained even after successful management of the hyperthyroid state.

Reduced survival times can be seen in the cats diagnosed as hypertensive as well as hyperthyroid. Successful control of hypertension may not restore longevity in such patients but quality of life would undoubtedly be improved.

Primary hyperaldosteronism (PHA) results from a spontaneous overproduction of aldosterone by the zona glomerulosa of the adrenal gland(s). This may be due to an adenoma, a carcinoma or hyperplasia. Cats with hyperaldosteronism classically present with signs relating to hypertension, hypokalaemia, or both.

It is not always easy to differentiate between primary and secondary hyperaldosteronism. In secondary hyperaldosteronism, the hormone becomes elevated secondary to raised renin levels (for example, as a consequence of reduced renal perfusion resulting from CKD).

Hypokalaemia can result from CKD, but long-term hypokalaemia can itself lead to nephropathy. Aldosterone is intensely pro-fibrotic (in the kidneys as well as potentially in other organs). CKD with a secondary aldosterone increase can therefore present a very similar picture to PHA with secondary renal consequences.

Renin measurement does not always differentiate, with many cases showing mid-range levels that are non-discriminatory. Adrenal imaging will be informative in those cases with a unilateral mass, but with a hyperplastic process, the adrenals may be normal in size or show only mild bilateral enlargement.

Fortunately, the treatment options for CKD and PHA differ minimally in such cases, where potassium supplementation, antihypertensive agents and spironolactone (competitive inhibitor of aldosterone) could be prescribed.

Where systemic hypertension is discovered, if no underlying cause is found after investigation then the diagnosis is best considered “open”, and as well as treatment for the high BP, repeat assessment for the possible underlying causes should be undertaken periodically (owner, patient and finances allowing).

Prompt management of hypertension (also in brief in Panel 2) is warranted; uncontrolled hypertension may contribute to progressive renal disease and cardiac remodelling, and the consequences of hypertension (particularly blindness) can have severe negative impacts on quality of life of our patients.

Where possible, any treatable underlying causes identified should be resolved or managed. This could include definitive treatment of hyperthyroidism (surgical thyroidectomy or radioactive iodine therapy), or adrenalectomy for PHA caused by a unilateral adrenal tumour. Treatment of hypertension is usually indicated while diagnostics are underway. Darbopoetin, used in cats with anaemia of kidney disease, will occasionally cause systemic hypertension as a side effect. Careful monitoring and a risk-benefit assessment would be required when it is used.

Where the underlying cause of hypertension is not amenable to resolution (CKD, bilateral adrenal disease, or where owner or patient factors preclude definitive therapy) or hypertension persists or recurs despite treatment (CKD, hyperthyroidism), ongoing medical management of hypertension is required.

Numerous pharmacological agents have the potential to modulate BP in cats, but the best evaluated in a clinical setting are amlodipine (calcium channel blocker; CCB), telmisartan (angiotensin receptor blocker; ARB) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-is), such as benazepril.

CCBs modulate vascular tone. In contrast, ARBs and ACE-is interrupt the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) at slightly different levels. Wherever RAAS blockade is commenced, it is essential to ensure the patient is first well hydrated.

The first licensed product for the control of systemic hypertension in cats was amlodipine. The International Society of Feline Medicine and Surgery has produced a consensus statement that outlines the recommendations for BP measurement and control of hypertension in cats, and highlighting the role of amlodipine in the effective control of hypertension (Taylor et al, 2017).

A chewable form of the drug has been shown to be both well accepted by cats, and effective in reducing the BP by an average of a little more than 20mmHg in mildly hypertensive cats (Huhtinen et al, 2015).

An earlier study (Elliott et al, 2001) and extensive clinical experience supports that amlodipine is capable of a powerful BP-lowering effect in patients with severe hypertension.

Telmisartan administered at a dose rate on 2mg/kg every 24 hours has been shown to reduce BP significantly in cats with naturally occurring, mild hypertension, regardless of cause, but including cats with CKD (average BP reduction 25mmHg after one month; (Coleman et al, 2019).

The drug gained a licence for the treatment of hypertension in cats some years ago. Prior to this telmisartan had already been established as an effective agent to control proteinuria (lower dose rate used) and in cases where both systemic hypertension and proteinuria are identified, it may be an appealing choice.

However the clinician should be aware that telmisartan has not been conclusively shown to effectively control severe hypertension, or protect from all target organ damage.

Although benazepril does have some BP-reducing effects, its effects are relatively weak and it is not specifically licensed for this indication. ACE-is are not usually recommended as a first line antihypertensive drug (Acierno et al, 2018).

In cases of severe hypertension, combination therapy may be required to achieve sufficient BP control. Telmisartan (or benazepril) can be used alongside amlodipine safely and effectively to achieve adequate BP control. In fact, combination therapy may be preferable in all cases.

In humans, ongoing intra-renal RAAS activation in the face of good BP control is possible in various disease states, and this process may continue unchecked if amlodipine is administered alone. This is undesirable, being detrimental to long-term renal function; concurrent RAAS blockade is warranted.

Side effects of antihypertensive treatment are uncommon. Hypotension (BP less than 120mmHg) can occur, but it is relatively rare even at the higher treatment doses (assuming that a careful upwards titration is used only when required). Fortunately, the agents discussed have a much more profound effect when the BP is raised, compared to when it is normal or near normal.

That said, dose increases should always be made gradually, and owners should be cautioned to be vigilant for signs of lethargy and weakness, which may indicate hypotension – particularly if the patient is prone to situational hypertension in clinic such that BP may have been overestimated.