18 May 2021

Figure 1. Digital pad corns. Note the variety of appearances from almost not visible on the left to deforming the pad on the right. In cases where a corn is suspected, but not easily seen, the pad can be wetted, which often allows better visualisation.

A corn is a focal circular area of hyperkeratisation found in the digital paw pads of the sighthound breeds (greyhound, whippet and lurcher). It is a common cause of severe debilitating lameness, with reported prevalence of 5.9% and 2.4% in health surveys of pet greyhounds (Lord et al, 2007; O’Neill et al, 2019).

Approximately 90% of corns occur in digits three and four, with 90% in the thoracic limbs (Guilliard et al, 2010). The lesion is analogous to heloma durum (corn or clavus) commonly occurring on the foot in humans (Roven, 1968).

A number of aetiologies have been proposed – these include viral infection, foreign body penetration and repeated mechanical trauma (Bohling et al, 2014). While a viral aetiology has often been stated, studies have failed to show any clear relationship (Balara et al, 2009).

None of the 100 corns submitted for canine papillomavirus PCR testing by the authors has been positive (Doughty, unpublished data). Furthermore, ultrastructural studies using electron microscopy have failed to reveal virus particles (Swaim et al, 2004).

Evidence for foreign body penetration was not identified from the clinical history, surgical exploration or histological examination in a case series published by Guilliard et al (2010). In addition, histological examination of more than 1,000 surgically excised corns has failed to identify a foreign body as the primary aetiology.

Plant material has been found in 4.5% of cases; however, this was all found in macerated cores thought to be due to secondary penetration (Doughty, unpublished data).

Repeated mechanical trauma has been proposed – as in humans – as the most likely aetiology in dogs (Guilliard et al, 2010; Bohling et al, 2014). Heloma durum in humans is thought to be caused by chronic pressure or friction where insufficient soft tissue exists between the skin and underlying bone (Freeman, 2002).

The mechanical trauma is caused by either extrinsic trauma such as ill-fitting shoes or high levels of activity, and/or from intrinsic factors such as bony prominences and faulty foot function (Yale, 1987).

In the dog, mechanical trauma as the aetiology is supported by a number of observations. The lesion is over-represented in digits three and four of the thoracic limbs of greyhounds – these digits have been shown to have greater vertical forces (Besancon et al, 2004). Concomitant anatomic deformity has been reported in 40% of dogs with corns, and when corrective surgery is performed the corn naturally regresses (Guilliard et al, 2010).

Numerous treatments are available, including conservative management, topical treatments and surgical intervention. Currently, surgical excision is reported to give the best results (Bohling et al, 2014; Doughty, unpublished data); however, a 50% recurrence exists after one year (Guilliard et al, 2010).

In humans, optimal surgical management of heloma durum centres on the correction of the abnormal stress (for example, condylectomy) as this leads to the regression of the lesion (Booth and McInnes, 1997; Freeman, 2002). This has also been noticed in dogs when the weightbearing aspect has been altered by distal digital ostectomy (Guilliard et al, 2010).

Due to this evidence, it has been suggested future treatments should focus on relieving local pressure (Bohling et al, 2014).

The interdigital joints are held in flexion by the superficial and deep digital flexor tendons (SDFT and DDFT) maintaining contact between the pad and the ground. The SDFT inserts on the proximal second phalanx and the DDFT on the flexor process of the third phalanx (P3). Both tendons are enclosed in a communal tendon sheath held in close proximity to the first phalanx (P1) by an annular ligament.

Severance of the DDFT alone results in a dorsal rotation of the P3; severance of the SDFT causes extension of the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP), but normal positioning of the distal interphalangeal joint. Severance of both ligaments extends both joints, flattening the digit with dorsal rotation of P3 from the action of the digital extensor tendon.

The proposed hypotheses were that by unloading the pad by a flexor tenotomy the lameness would resolve and the corn would exfoliate.

In a case series, 161 corns in 100 dogs were treated by either a full digital flexor tenotomy or by a superficial digital flexor tenotomy. The surgery was performed by one author (Mike Guilliard).

The degree of lameness can vary from mild to non-weightbearing, but is typically worse on hard, rough surfaces.

The physical appearance of a corn can vary from an obvious plug of hard keratin to very subtle changes to the surface of the pad (Figure 1). There should be a repeatable pain response to mediolateral or dorsopalmar/plantar digital pressure. A thickening of the pad can often be felt on mediolateral palpation.

A dark central spot from the macerated core is often present and if in doubt, mediolateral radiographs should be taken to exclude a radiopaque foreign body.

All consecutive cases of dogs presented with corns over a two-year period were recruited. Choice of surgical technique was based on the following:

For both surgeries the dog is anaesthetised, prepared for surgery and placed in lateral recumbency with the affected digit uppermost. By holding the digit in forced extension the taut flexor tendons are easily palpable on the palmar/plantar aspects of P1 and the metacarpus/tarsus.

A tourniquet is unnecessary in either procedure.

With the digit held by an assistant in full extension, a linear skin incision starting about 3mm from the metacarpal/tarsal pad is made over the tendon. Large veins are visible running beside the tendon sheath, often with a communicating vein over the tenotomy site.

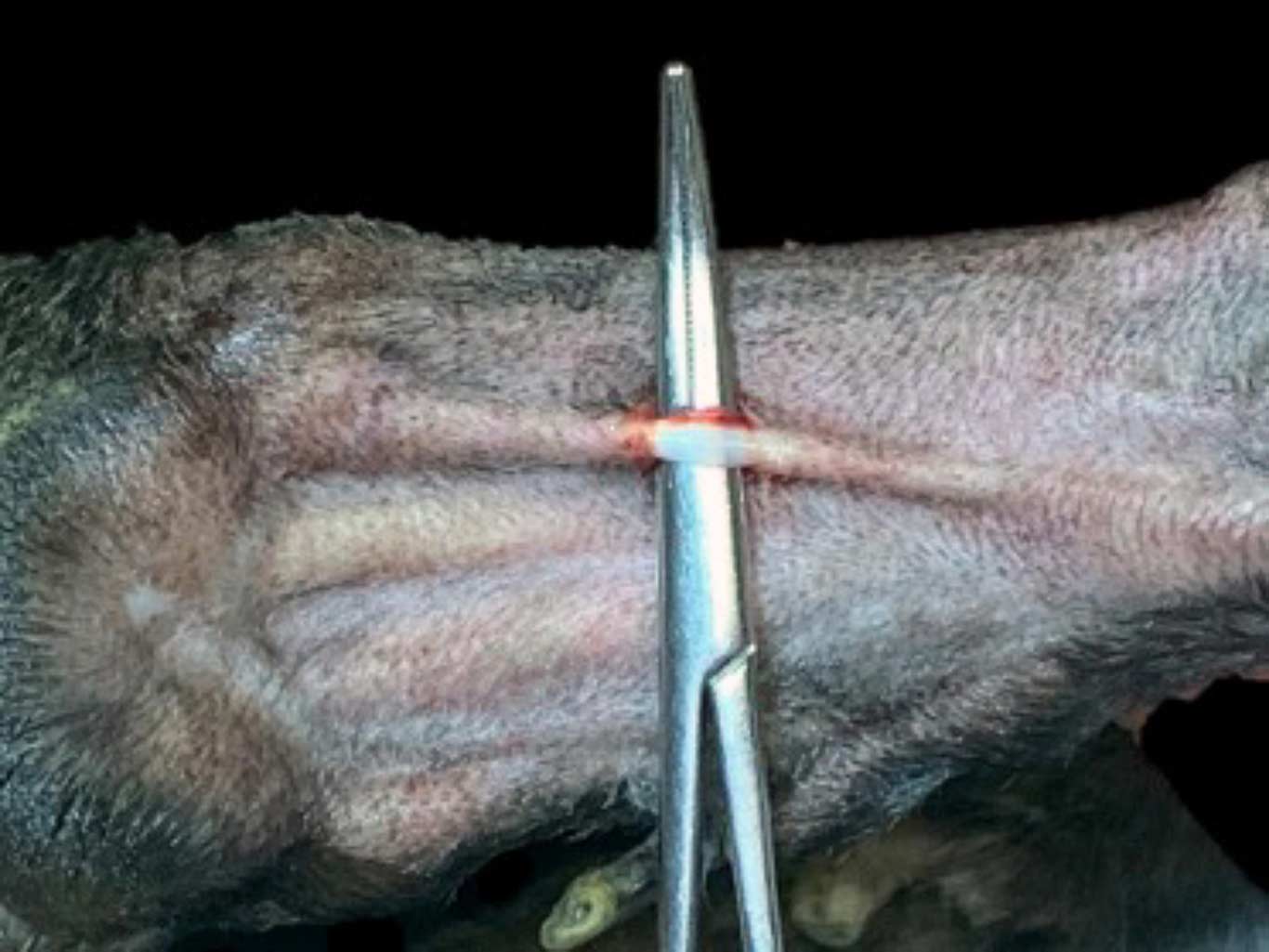

The tendon sheath is carefully dissected free of its connective tissue, allowing fine curved artery forceps to be placed under the tendons (Figure 2). Alternatively, the tendon sheath can be incised and the tendons again isolated.

The tendons are transected and the cut surfaces immediately separate from each other. Both superficial and deep flexor tendons consist of several bundles, and it is important to inspect the surgical site to ensure all bundles have been cut. The skin is closed with two or three simple sutures.

Again, with the digit held in forced extension, a linear skin incision 1cm to 2cm in length is made along the tendon at the distal third of the metacarpus/tarsus.

The SDFT is immediately exposed and again dissected free of connective tissue, enabling small curved forceps to be placed between it and the underlying DDFT allowing transection (Figure 3).

The corn is not surgically removed, hulled out or pared down.

A protective dressing is left on for 24 hours. The dog can have lead exercise for a further seven days on clean, dry surfaces followed by normal free exercise.

NSAIDs are given for five days.

Follow-up in all cases was by telephone at approximately seven days and eight weeks post‑surgery, and in 30 dogs with full tenotomies after one year. The superficial tenotomy series was followed up from six months.

The seven-day follow-up was to assess the degree of lameness, demeanour and willingness to exercise, while the eight-week follow-up assessed degree of lameness and corn presence.

The characteristics of all corns are summarised in Table 1.

| Table 1. Characteristics of all corns | |

|---|---|

| Characteristic | |

| Age (years, mean [SD]) | 6.5 (2.5) |

| Sex, percentage of males | 69% |

| Duration of corn to presentation (months) mean (SD) | 18.0 (17.8) |

| Dogs with multiple corns percentage | 38% |

| Previous treatments for corns (hulling and/or excision) | 43% |

| Concomitant injury | 26% |

| Corns located in digits three and four | 89% |

| Corns located in thoracic limbs | 88% |

| SD = standard deviation | |

The comparative outcomes of both full and superficial tenotomies are summarised in Table 2.

| Table 2. The comparative outcomes of both full and superficial tenotomies | ||

|---|---|---|

| Full tenotomy | Superficial tenotomy | |

| Improvement at seven days | ||

| None | 0 | 0 |

| Slight | 1 | 2 |

| Moderate | 11 | 12 |

| Great | 70 | 19 |

| Lameness at eight weeks | ||

| Severe | 0 | 3 |

| Moderate | 0 | 0 |

| Slight | 13 | 6 |

| None | 70 | 24 |

| Lameness at one year | ||

| Severe | 0 | |

| Moderate | 1 | |

| Slight | 6 | |

| None | 23 | |

At eight weeks, 97% of dogs had slight or no lameness and the corn had exfoliated in 95% of dogs. The review of the outcome from six months post-surgery of all superficial digital flexor tenotomies is summarised in Table 3.

| Table 3. Superficial tenotomy review from six months | |

|---|---|

| Lameness | |

| Very lame | 7 |

| Moderate | 0 |

| Slight | 2 |

| None | 15 |

| Breakdown of very lame cases | |

| No response to treatment | 1 |

| Recurrence of same corn | 3 |

| Corns in other digits, index digit no corn | 3 |

Five racing greyhounds returned to racing with no adverse effects on performance.

Regarding complications:

Prior to this report, in three cases with other anatomical abnormalities on the same foot full tenotomy was not successful as a result of concussive pain on the palmar aspect of the digit. It was concluded that the support of adjacent digits is necessary to prevent this occurrence.

Superficial tenotomy, however, results in partial collapse of the PIP joint, but retains a degree of flexion from the action of the DDFT, therefore in theory not resulting in palmar concussion. For this reason it was selected for the more complex cases (missing digits, previous tenotomy, anatomical deformity).

The initial success of superficial tenotomy led to it being the preferred procedure in all cases, although both procedures give comparable results. Superficial tenotomy can be undertaken on multiple digits on the same or different feet in the same surgical session.

The postoperative morbidity is low and improvement is rapid.

Corn recurrence was the only major complication after superficial tenotomy and was successfully treated by full tenotomy.

Multiple corn presentation and further corn occurrence was seen in 38% of dogs, and factors influencing this may be a genetic predisposition and in some dogs the increased loading of the other digits following tenotomy.

The limitations of this report are the reliance on owner assessments and possible author bias as no independent contact was made.

Corns are a common cause of severe lameness in the sighthound breeds and no reported treatment has good efficacy. Digital flexor tenotomies have shown to give excellent short-term and medium-term results, with few complications.

Owners report improved demeanour, willingness to exercise and, in most cases, no lameness. Its success is now, through social media, recognised globally, supported by a flexor tenotomy Facebook page with more than 1,500 members.

Since the conclusion of this study, several more cases of corn recurrence following initial successful superficial digital flexor tenotomy have been seen. This is due to contraction of a thickened fibrous band at the site of the original tenotomy at the metacarpus/tarsus restoring the original anatomic positioning of the digit.

Surgical treatment involves dissecting out this fibrous band with good results. A tourniquet is advisable.

As a result of this complication, all SDFT surgeries are now tendonectomies removing approximately 10mm of tendon.

A new study looking at the outcome of this revised technique is now under way in collaboration with Eithne Comerford and Pippa Williams at the University of Liverpool, and there is a call for suitable cases. These are limited to dogs with a single corn and no other orthopaedic problems or previous flexor tenotomies.

At present the ethical review only allows two designated surgeons, Mike Guilliard ([email protected]) and Prof Comerford ([email protected]), so if there is further interest or suitable cases, please contact us.