21 Feb 2025

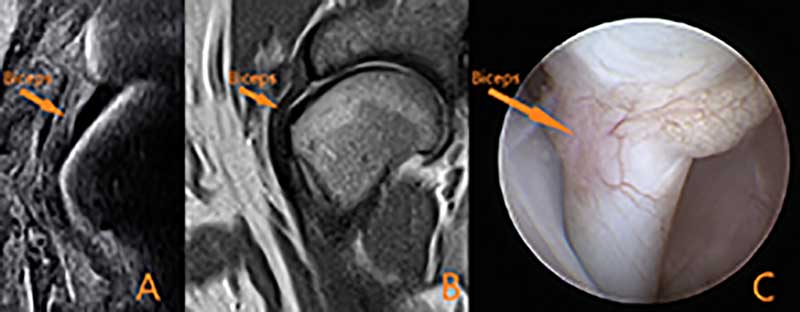

Figure 1. Images A and B are transverse CT images showing how the location of a mineralisation within the insertion of the supraspinatus can vary between patients. Image C shows the location of the biceps tendon (yellow circle) and its close proximity to the mineralised supraspinatus. Images D and E are mediolateral radiograph and CT views. From these single images, it is not possible to determine if the mineralised supraspinatus has the potential to impinge the biceps; cross-sectional imaging (as in A, B and C) would be required. Image F is an arthroscopic view of the mineralised supraspinatus bulging into the joint capsule of the biceps sheath.

The canine shoulder, a synovial joint, allows extensive multi-directional motion. Although motion is primarily in the sagittal plane, it also facilitates lateral, medial, internal and external movements.

Stability is ensured through passive (static) and active (dynamic) elements, which undergo biomechanical stress. Excessive biomechanical stress (either in the form of an acute overload or chronic repetition) can result in tissue injury.

Passive stabilisers include the limited joint capacity, synovial fluid adhesion-cohesion (“suction-cup” effect), concavity compression, and capsuloligamentous constraints. Active stabilisers, referred to in humans as the “cuff” muscles, include the: supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis. Additional muscles, such as the long head of the triceps, deltoid, and teres major, also provide some lesser contribution to joint stability.

Shoulder disorders commonly cause lameness in companion and active (sports, working) dogs, with the shoulder accounting for 30% of injuries to agility dogs (Cullen et al, 2013; Pechette Markley et al, 2021). The most described conditions include tendon injuries (biceps/supraspinatus), medial shoulder syndrome, dislocation, and infraspinatus muscle contracture.

The supraspinatus muscle, originating in the scapula and attaching to the humerus, extends the shoulder, advances the limb and stabilises the glenohumeral joint. Supraspinatus tendinopathy (ST) typically affects medium to large active dogs – particularly agility breeds – due to excessive mechanical loads and rapid movements. Concurrent thoracic limb pathologies may contribute to the disease process due to compensatory gait changes (Canapp et al, 2016).

The author frequently observes “incidental” mineralisation of the tendinous insertion of the supraspinatus on CT imaging of dogs with developmental elbow disease.

ST causes varying degrees of lameness, which often worsen with activity and are unresponsive to rest or anti-inflammatory treatments. Diagnosis includes palpation and imaging techniques, such as musculoskeletal ultrasound (MSK US) and MRI, revealing changes in tendon structure (Canapp et al, 2016). MRI should be interpreted carefully to avoid misdiagnosing the normal trilaminar appearance as ST and avoiding “magic angle” artefact.

ST management includes 8 to 12 weeks of restricted activity and a structured rehabilitation programme. Additional therapies such as photobiomodulation, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, and orthobiologic treatments (platelet-rich plasma therapy with or without stem cells) show promising results (Danova and Muir, 2003; Becker et al, 2015; Kern et al, 2023).

Surgery, though controversial, has been reported and may involve calcification removal or tendon bulk reduction (particularly to relieve pressure on the biceps tendon, as these two tissues are in close approximation and impingements can occur; Muir and Johnson, 1994; Lafuente et al, 2009).

The biceps brachii tendon starts at the scapula’s supraglenoid tubercle, passes through the glenohumeral joint and intertubercular groove. The biceps inserts at the ulnar and radial tuberosities. It bends the elbow and aids shoulder extension and stabilisation. The biceps tendon sheath, an extension of the shoulder joint, encases the biceps tendon proximally.

Biceps tendinopathy (BT) causes forelimb lameness – especially in large, active dogs and agility dogs (Tomlinson, 2023). Biceps pathology can be primary (inflammation, degeneration, tears) or secondary (as alluded to previously; a common secondary cause is impingement from a swollen and/or mineralised, supraspinatus tendon; Figure 1).

Primary inflammation may result from injury during simultaneous shoulder flexion and elbow extension or direct trauma (Gilley et al, 2002; Wernham et al, 2008). More commonly, they stem from repetitive stress or wear and tear, leading to a degenerative tendinopathy, characterised by disorganised collagen, mucoid material, cell death, or calcification, without active inflammation (Khan et al, 2006).

Degenerative tendinopathy often involves swelling of the surrounding sheath, known as bicipital tenosynovitis, which may occur independently or result from other shoulder problems (Davidson et al, 2000; Gilley et al, 2002). Issues within or outside the shoulder joint, such as an enlarged supraspinatus tendon, osteochondrosis, arthritis, or medial shoulder syndrome, can also cause BT problems.

Lameness severity from BT pathology varies from sporadic stiffness to severe, persistent lameness (Davidson et al, 2000; Wernham et al, 2008). Physical examination often reveals pain on palpation or during the “biceps stretch test” (Leeman et al, 2016; Bergenhuyzen et al, 2009; Figure 2).

Imaging techniques such as radiographs, CT scans, MRI, MSK US, and arthroscopy are recommended for precise diagnosis (Lane et al, 2023; Figure 3).

Contrast arthrograms can be useful if attempting to obtain a diagnosis with radiography or CT. Ultrasound is ideal for its cost, duration, and minimal sedation requirements, which also make it optimal for repeated assessments.

Treatment depends on the injury extent, presence of tenosynovitis and related conditions (Lane et al, 2023). Options include conservative methods such as therapeutic exercise programmes, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, photobiomodulation, or surgical interventions such as tenodesis and tenotomy for severe cases (Wall and Taylor, 2002; Cook et al, 2005).

Recent studies suggest conservative treatment for tenosynovitis and minor BT damage, reserving surgery for severe tears (Lane et al, 2023). Combining conservative and surgical treatments with newer techniques such as ultrasound-guided incisionless tenotomy shows promise (Esterline et al, 2005; Lane and Schiller, 2021).

Medial shoulder syndrome (MSS) is a phrase that has been used over the past decade to describe pathology to the support structures on the medial aspect of the shoulder joint, predominantly the subscapularis muscle and medial glenohumeral ligament. Although this phrase is useful, clinicians should aspire to be more specific with their diagnosis, identifying the exact tissue affected.

MSS is often due to chronic repetitive strain or overuse, leading to tissue degeneration (Maganaris et al, 2004; Marcellin-Little et al, 2007). MSS diagnosis combines clinical history, examination and imaging. It is common in middle-aged, larger breed and performance dogs – particularly agility dogs – presenting as chronic lameness.

Diagnostic imaging is best done with MRI and MSK US, with arthroscopy also able to produce a good assessment of the most frequently located injuries (Canapp et al, 2016).

Management includes 8 to 12 weeks of restricted activity and rehabilitation, using a hobble vest to limit shoulder abduction. Rehabilitation starts with manual therapies and progresses to muscle strengthening. Adding extracorporeal shockwave therapy and intra-articular platelet-rich plasma therapy is anecdotally reported as beneficial.

Surgical options for severe cases include biceps tendon transposition, subscapularis imbrication, prosthetic repair and radiofrequency-induced thermal capsulorrhaphy (Pettitt et al 2007; Pucheu and Duhautois, 2008; Franklin et al, 2013; O’Donnell et al, 2017; Hayashi and Markel, 2021; Rocheleau et al, 2023). Surgery is typically reserved for shoulders that are unstable.

The infraspinatus muscle, originating on the scapula and attaching to the humerus, functions predominantly as a flexor, abductor, and external rotator of the shoulder.

Infraspinatus myopathy and contracture result from repetitive microtrauma, acute strains or osteofascial compartment syndrome, leading to muscle fibrosis and restricted blood flow (Pettit et al, 1978; Matava et al, 1994; Mikkelsen and Ottesen, 2021).

Typically seen in medium to large breed dogs – especially working or hunting dogs – it presents unilaterally with symptoms such as sudden limb lameness, muscle fibrosis and pathognomonic gait abnormalities (limb circumduction and a paw flip motion when walking).

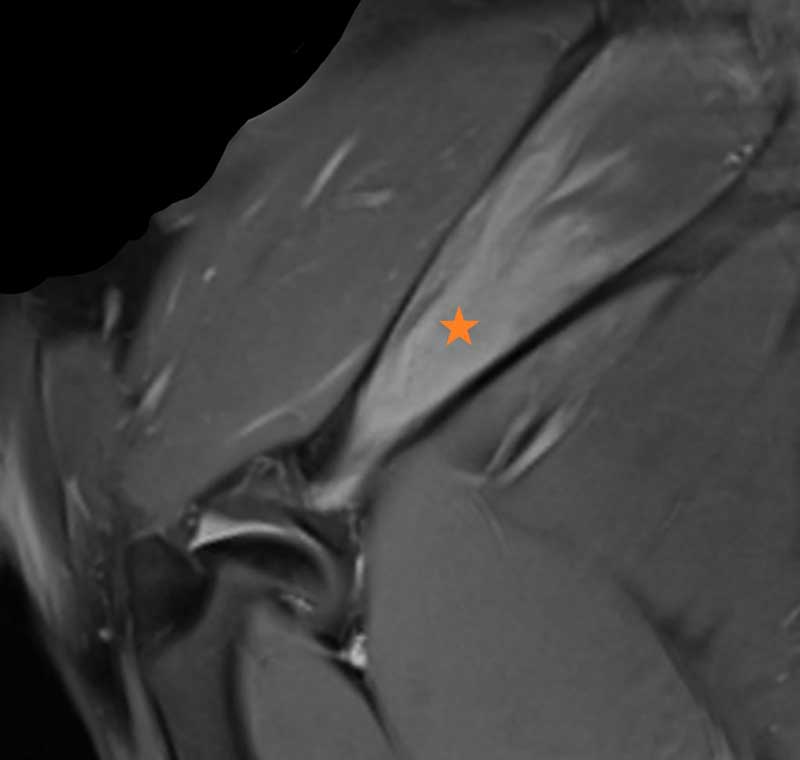

The affected limb exhibits external rotation, flexion and abduction of the shoulder. Diagnosis in later stages shows increased echogenicity of the muscle on MSK US which, along with CT and MRI, can confirm the condition in both acute and chronic phases (Murphy et al, 2008; Mikkelsen and Ottesen, 2021; Figure 4).

In the early stages of infraspinatus myopathy, interventions such as therapeutic ultrasound, shockwave therapy, and stretching may help maintain tissue flexibility and prevent contracture.

Surgical options include fasciotomy to decompress the muscle.

However, most cases are diagnosed in their chronic phase, requiring tenotomy of the infraspinatus to release the muscle, sometimes accompanied by partial tendon resection. Surgical release generally results in a good to excellent recovery, with early rehabilitation important to prevent new adhesions.

Injuries to the soft tissues surrounding the canine shoulder can frequently result in a forelimb lameness. Definitive diagnosis often requires advanced diagnostics such as MRI, MSK US or arthroscopy.

Therefore, practitioners without access to these should pay particular attention to the patient history and physical examination findings to identify the cause of lameness.