7 Dec 2018

Figure 2. Generally, cats prefer glass, metal or ceramic rather than plastic bowls. They also prefer wide, shallow bowls filled to the brim. Image © pelagey18 / Adobe Stock

Inflammation of the bladder wall – or cystitis – is a common presentation in cats and dogs. Causes vary significantly between the two species, as well as males and females, and can be due to both infection or irritation – both of which may be the result of a wide variety of inciting issues. This article will focus on feline idiopathic cystitis and canine bacterial cystitis.

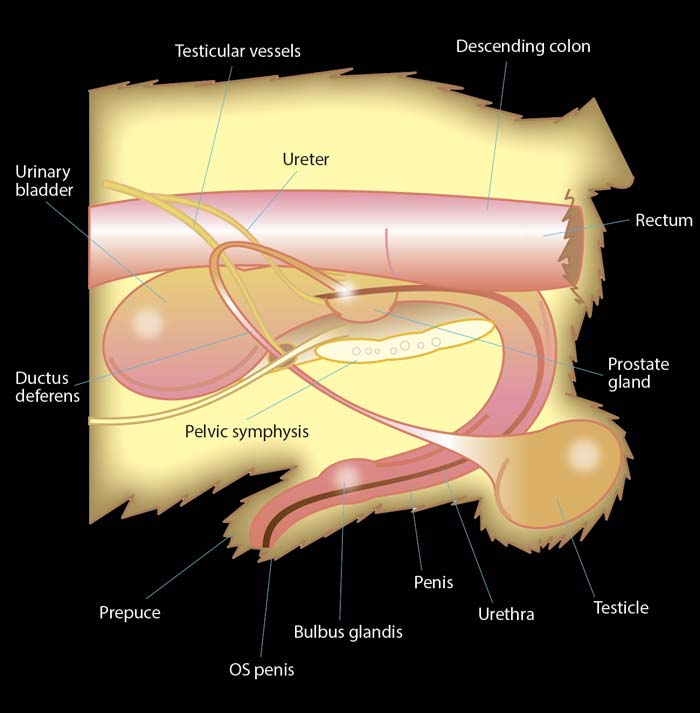

The lower urinary tract is comprised of the bladder, urethra and, additionally in males, the prostate.

The bladder is a muscular, pear-shaped, hollow organ that lies in the midline of the caudal abdomen and stores urine. The body points cranially and the narrow end, known as the neck, points caudally. The bladder is lined with transitional epithelium, which allows it to expand as it fills with urine and smooth muscle fibres surround this epithelial layer.

Only the body of the bladder expands into the abdominal cavity and has an outer layer of peritoneum. The neck of the bladder has a sphincter to control the flow of urine out of the bladder. Urine is passed from the bladder into the urethra, which runs through the pelvic cavity and opens to the outside of the body Figure 1).

Cystitis patients will often have small bladders and may show pain and/or discomfort on palpation of the caudal abdomen. In chronic cases, the bladder wall may feel small, thickened and irregular, with palpation causing reflex attempts to micturate.

Studies into the pathophysiology of cystitis have focused on the increased bladder wall permeability and increase on inflammatory mediators attributed to decreased concentrations of surface urothelial glycosaminoglycans (GAGs; Buffington et al, 1996). The GAG layer provides a protective barrier for the sensitive bladder urothelium, which acts to prevent the adherence of bacteria and crystals.

Damage to the urothelium and the overlying GAG layer can allow the contents of the urine to activate the C-fibres, which may be perceived as painful by the brain.

FLUTD is an umbrella term for several disorders affecting the bladder and/or urethra in cats. Bacterial cystitis is uncommon in cats younger than 10 years old, with previous reported prevalence of less than 3% (Buffington, 2011).

However, the most common cause of FLUTD is feline idiopathic cystits (FIC), which is present in up to 64% of cats with lower urinary tract signs (Gerber et al, 2005).

FIC is the name given to FLUTD when signs of cystitis are exhibited, but where no obvious underlying cause can be found. It has been likened to interstitial cystitis – an idiopathic bladder disease affecting people.

FIC is a diagnosis of exclusion and represents a syndrome involving derangements not only within the urinary bladder, but within a complex interaction between numerous body systems – in particular, the nervous system and adrenal glands (Buffington, 2011).

The aetiology is not fully understood, but cats with anxious personalities are predisposed to FIC (Bowen and Heath, 2005). As a result of the diverse nature of the underlying causes, cats of any age, breed and gender can be affected by FIC.

Several risk factors predisposing a cat exist. These include:

Cats with FIC usually present with one or more of a range of signs:

Stress is believed to have an important role in prompting or exacerbating FIC. A study identified a link between development of FLUTD and cats that display fearful, nervous and/or aggressive behaviour (Buffington et al, 2006). Evidence also exists of a direct correlation between mental and physical health.

Stress takes its toll on the health of cats, and research has demonstrated an increase in sickness behaviours associated with stressful events (Stella et al, 2011). Cats are naturally solitary hunters that may choose to live in groups of related individuals. They do not like to share essential resources with cats from other social groups; therefore, the provision of adequate resources in the home is a key factor in minimising stress.

The five key resources are water stations, feeding stations, litter trays, resting places (preferably high up), and points of entry and exit. Each cat should be able to access all resources without competing with others. Microchip-operated cat flaps in internal doors can offer a means to separate cats for private access to feeding and litter boxes. It is recommended the number of litter trays equals the number of cats, with one extra.

Much can be said about environmental changes that may reduce the risk of FIC in relation to litter box management (number, type, access, content and hygiene); provision of suitable feeding and watering stations; reducing inter-cat disharmony; and positive environmental enrichment that stimulate natural cat behaviours (Buffington et al, 2006; Gunn-Moore and Caney, 2009).

FIC is a complex disorder that often occurs when a vulnerable patient is exposed to stressors; therefore, a thorough history is essential to the investigations. Managing cats with FIC will take a multimodal approach and should include the following as directed by a vet:

Cystitis is a common problem seen in canine patients in general practice, with 14% of dogs acquiring a bacterial cystitis in their lifetime (Ling, 1984).

Bacterial infection is the most common cause of cystitis in dogs, unlike cats in which most cases are idiopathic and sterile. According to Sturgess (2016), little data is available for canine cystitis and idiopathic cystitis is not a well-described condition. Most dogs with cystitis will have a defined underlying cause, with infection and urolithiasis being most common. Other causes of cystitis include bladder neoplasia and prostatic disease, and can be drug-induced.

Canine urinary tract infections (UTIs) can be classified as either uncomplicated or complicated (Warland and Bestwick, 2017).

An uncomplicated or simple UTI has no underlying cause and the dog is healthy, with a normal urogenital tract, and the infection does not occur more frequently than every four to six months.

In complicated UTIs, an underlying abnormality exists that predisposes the dog to UTIs or fail treatment. This abnormality may include concurrent diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, or abnormal function in the anatomy of the urogenital tract, which may predispose the dog to acquire a UTI or make treatment difficult. Entire male dogs are always considered to have a complicated UTI due to possible involvement of the prostate.

Bacterial cystitis is generally uncomplicated and most commonly seen in older female dogs (Chandler, 2018). They can be successfully treated by the vet with antibiotics following culture and sensitivity testing.

Clinical signs are similar to that of the cat, and may include dysuria, stranguria, haematuria and pollakiuria. According to Westropp et al (2012), pollakiuria is the most common clinical sign reported; however, some bacterial UTIs can be asymptomatic.

Management of canine bacterial cystitis includes the following:

VNs play a crucial role in aiding the vet with diagnosis and treatment of both canine and feline lower urinary tract disease. The information discerned from the owner aids in the diagnosis of lower urinary tract disease, and the discussion of the diagnostic and treatment plan with the client is crucial to the client’s understanding of the condition, therefore boosting compliance.

Following diagnosis, VNs can be responsible for advising clients on both nutritional and stress management of these urinary cases.