20 Aug 2018

Combined management of feline hypertension, CKD and proteinuria

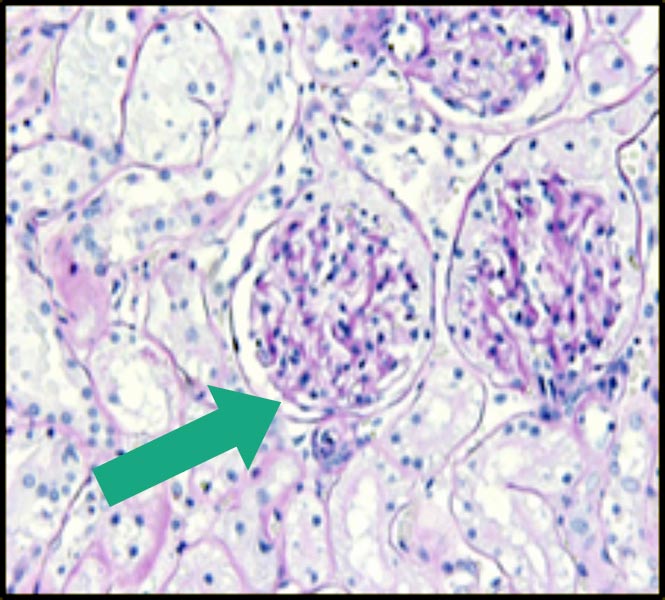

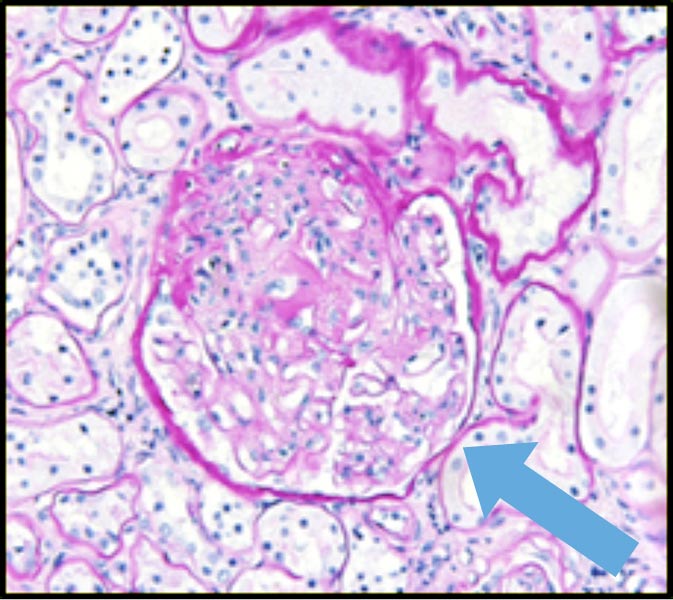

Figure 1. Glomerular changes with hypertension and chronic kidney disease. (1a) Normal feline glomerulus (green arrow). (1b) Glomerulus from a cat with chronic kidney disease and hypertension demonstrating glomerular hypertrophy (increase in size and volume of glomerulus) and glomerulosclerosis (thickening of basement membrane and mesangial matrix expansion; blue arrow).

Systemic hypertension is a common condition in ageing cats.

Large studies have shown systolic blood pressure (SBP) increases with age1,2 and the average age at diagnosis of systemic hypertension is approximately 14 years old3. In cats older than 9 years of age, SBP increases by approximately 0.4+/-0.1mmHg/100 days4. This highlights the importance of measuring blood pressure as part of annual wellness checks – particularly in cats older than 7 to 9 years of age.

The International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) and the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) have produced guidelines for SBP categories in cats (and dogs) associated with the risk that a given blood pressure may result in target organ damage (TOD), particularly affecting the eyes, kidneys, cardiovascular system and CNS (Table 1)5.

| Table 1. International Renal Interest Society and American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine classification of blood pressure and hypertension | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category | SBP (mmHg) | TOD risk |

| Normotensive | Less than 140 | Minimal |

| Pre-hypertensive | 140 to 159 | Mild |

| Hypertensive | 160 to 179 | Moderate |

| Severe hypertension | More than or equal to 180 | Severe |

| SBP = systolic blood pressure, TOD = target organ damage. | ||

These risk categories have been updated and include a prehypertensive category (Panel 1).

Boris is a 12-year-old neutered male domestic shorthair presenting for a routine wellness examination.

As part of his examination, his blood pressure was measured and his average systolic blood pressure (SBP) was 158mmHg over five readings. After a routine biochemical profile including symmetric dimethylargine concentration and urinalysis performed, results showed he has International Renal Interest Society stage two chronic kidney disease (CKD). Substaging showed Boris’ blood pressure to be in the pre-hypertensive category (140mmHg to 159mmHg). Boris, therefore, does not require antihypertensive medication at the moment, but a possibility exists his SBP will continue to increase with time and he may be at risk of developing hypertension in the future – particularly because he also has CKD. It would, therefore, be recommended Boris has his blood pressure checked at least every six months so he can be monitored for the future development of hypertension.

The pre-hypertensive category can be used to help decide when increased monitoring of blood pressure may be indicated. In particular, this is important for cats older than nine years of age or with clinical conditions that increase the risk of systemic hypertension.

Hypertension, when diagnosed, can be classified by underlying aetiology (Panel 2).

Situational: where stress or anxiety in the clinic results in an increase in systolic blood pressure, previously called white-coat hypertension. No treatment is recommended for situational hypertension.

Idiopathic: hypertension is diagnosed, but no underlying condition is associated with development of hypertension identified.

Secondary hypertension: the presence of hypertension either associated with underlying disease conditions or drug administration.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of systemic hypertension can be made in the following ways:

- On the basis of a single measurement of SBP more than 160mmHg when TOD (Table 2) – particularly ocular or CNS (seizures and altered mentation) – is recognised.

- In cats with SBP more than 160mmHg, but no TOD, it is important to ensure increased SBP is persistent. SBP should be rechecked ideally after 7 to 14 days and if high in two or more occasions, together with clinical concern for systemic hypertension (such as senior or geriatric cat, predisposing disease condition identified; for example, chronic kidney disease [CKD] or hyperthyroidism), a diagnosis of systemic hypertension can be made.

- In a cat older than seven years of age with no concurrent disease associated with hypertension and no evidence of TOD, rechecking SBP on a third occasion may be required to diagnose hypertension and exclude situational hypertension.

- In a cat younger than seven years of age with no concurrent disease, where the risk of hypertension is low, identifying high SBP more than 160mmHg is more likely to indicate situational hypertension. No treatment is recommended for situational hypertension.

| Table 2. Target organ damage reported in cats | |

|---|---|

| Target organ | Lesions identified |

| Eyes | Hyphaema, retinal haemorrhage, focal bullous retinal detachments, retinal detachment (hypertensive retinopathy/choroidopathy), retinal vessel tortuosity and secondary glaucoma. |

| Cardiovascular system | Left ventricular hypertrophy, heart murmurs and gallop heart sounds. |

| CNS | Seizures, vestibular signs, behavioural changes, depression/obtundation, vocalisation and ischaemic myelopathy. |

| Kidneys | Glomerular hypertension, glomerulosclerosis and proteinuria. |

Concerns with hypertension, proteinuria and kidneys

Hypertension has been reported to affect between 20% to 60% of cats with CKD and, while CKD may be a risk factor for the development of hypertension, the kidneys are also important target organs for hypertensive damage. Therefore, in all cats diagnosed with CKD, IRIS staging should be performed with substaging for blood pressure and proteinuria6.

Proteinuria and feline CKD

In cats older than nine years of age with CKD due to tubulointerstitial nephritis, the magnitude of proteinuria is typically low7.

However, proteinuria remains an important risk factor7-9 for:

- development of azotaemic CKD

- progression of CKD

- survival time

Studies that have evaluated antiproteinuric agents in cats with CKD have not documented survival advantage, despite reducing proteinuria10,11. This may be due to small study size or because most cats with CKD have low levels of proteinuria. Nevertheless, given the strong association with survival, management of proteinuria is important, and in cats with CKD when proteinuria is persistent, treatment is recommended6.

Proteinuria and feline hypertension

In-health renal autoregulation maintains pressures within the glomerular capillaries and, therefore, glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

High systemic pressures can override renal autoregulation, resulting in increased glomerular capillary pressures and damage to the glomerular capillaries, referred to as glomerular hypertension and glomerulosclerosis (Figure 1). This can result in the glomerular filtration barrier being ”leaky” to proteins. Therefore, proteinuria is an anticipated clinical finding in patients with systemic hypertension indicating ongoing TOD (Figure 1)7.

Cats with hypertension and CKD show greater proteinuria than normotensive cats with equivalent stage of kidney disease. At postmortem, hypertensive cats show glomerular and arteriolar hypertensive injury7,12,13.

In a study that evaluated cats with systemic hypertension, proteinuria was the only factor significantly associated with survival, despite all cats being treated for their hypertension3. This indicates management of not just hypertension, but also proteinuria, may be important when considering the hypertensive cat with a diagnosis of CKD.

Background: Fleur is a 14-year-old neutered female domestic shorthair noted to be polydipsic (PD) by her owner for the past couple of months. Concern exists about weight loss and variable appetite. On physical examination, her kidneys are small and irregular..

Investigation: Doppler systolic blood pressure (SBP) is assessed – with an average of 175mmHg – and indirect fundic examination reveals focal bullous retinal detachments in the left eye. Fleur had blood work performed to evaluate renal function. This showed she is azotaemic (creatinine 212μmol/L – reference interval 80μmol/L to 203umol/L) with increased symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA; 16mg/dL – reference interval less than 14mg/dL). Urinalysis confirms inappropriately dilute urine (urine specific gravity 1.02), but is otherwise unremarkable.

Diagnosis and staging: evaluating her kidney function, history of PD and renal palpation, Fleur is diagnosed with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Repeat assessment of renal function would be required in two to four weeks to confirm stability of disease before International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) staging should be performed. However, based on this first assessment, Fleur would be considered IRIS stage two. The IRIS recommends substaging for both blood pressure and proteinuria. On the basis of her blood pressure and fundic examination, Fleur would be diagnosed as “hypertensive with moderate risk of ongoing target organ damage” according to the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine guidelines. Substaging for proteinuria identified Fleur was borderline proteinuric (UPC 0.3).

Management: Fleur was started immediately on antihypertensive treatment with amlodipine besylate (0.625mg by mouth every 24 hours) and was also discharged with a renal diet, which it was recommended was gradually introduced. A re-examination appointment was booked for one week.

On re-examination: the following week Fleur was reported to be brighter, had taken to her renal diet well and her owners had no problems administering her amlodipine tablets. Repeat assessment of blood pressure showed good control SBP 150mmHg, so amlodipine therapy and her renal diet was continued, as previously prescribed. Fleur was re-examined after three weeks and, at this point, was re-evaluated in terms of her blood pressure and renal function, having been on therapy for both her hypertension and CKD for one month. Her renal values were stable (creatinine 204μmol/L, SDMA 17mg/dL), urine specific gravity 1.024 and her blood pressure stable (144mmHg). Repeat assessment of proteinuria indicated she was non-proteinuric (UPC 0.18) after introduction of both the renal diet and good blood pressure control. No additional therapy was required for proteinuria at this time. In the longer term, it was recommended Fleur was re-examined after three to four months or sooner if concerned any change occurred in her clinical status.

General recommendations for treatment of systemic hypertension

If a diagnosis of systemic hypertension has been made, irrespective of underlying conditions, prompt introduction of antihypertensive therapy is vital to prevent ongoing TOD (Table 2).

For cats in the UK, the licensed product for treatment of systemic hypertension is the calcium channel blocker amlodipine besylate. This is an effective and well-tolerated once-daily antihypertensive agent available in a flavoured formulation, making this an easily administered medication for most cats. On average, a 20mmHg to 50mmHg reduction in SBP is expected when amlodipine is started.

Goals for antihypertensive therapy are:

- Gradual reduction in SBP to reduce the risk of TOD to mild (less than 160mmHg) or preferably minimal (less than 140mmHg; Table 1).

- Avoid hypotension (weakness, lethargy associated with SBP less than 120mmHg); it is rare to identify hypotension in cats treated with amlodipine.

SBP should be rechecked 7 to 14 days after starting amlodipine treatment. If adequate control of hypertension is not achieved (SBP less than 160mmHg) then the dose of amlodipine should be increased from a starting dose of 0.625mg/cat every 24 hours by mouth to 1.25mg/cat every 24 hours by mouth, and repeat SBP measurement performed again after a further 7 to 14 days. The higher dose of amlodipine is often required for cats with starting SBP more than 200mmHg14.

For cats with severe CNS TOD (such as seizures), hospitalisation should be recommended for careful monitoring and titration of antihypertensive therapy. In this emergency situation, amlodipine is the preferred antihypertensive agent, providing administration of an oral medication is appropriate.

Hospitalisation and close monitoring may also be considered for cats with severe ocular TOD (hyphaema/retinal detachment). However, in most cats with ocular TOD and hypertensive cats without overt ocular TOD, starting therapy with amlodipine and re-examination for repeat assessment of SBP within 7 to 14 days is usually appropriate.

Recommendations for treating hypertension, CKD and proteinuria

As CKD is associated with hypertension in cats, it is common to be faced with the situation where it is necessary to start treatment for both CKD and hypertension simultaneously.

Amlodipine is a well-tolerated treatment for hypertension in cats with CKD of all stages and starting treatment should not be expected to cause any decline in renal function or increase in creatinine concentration. Amlodipine therapy can be started concurrently with dietary management of CKD. Transition to a commercially available renal diet should always be made gradually to improve acceptance of the new diet.

Assessment of proteinuria is recommended in all cats diagnosed with CKD as part of IRIS staging. In a study that evaluated 141 cats with systemic hypertension, of which 58% had evidence of pre-existing azotaemic CKD (IRIS stage two and above), the median urine protein to creatinine (UPC) at diagnosis of hypertension was 0.31 (25th percentile 0.19, 75th percentile 0.59).

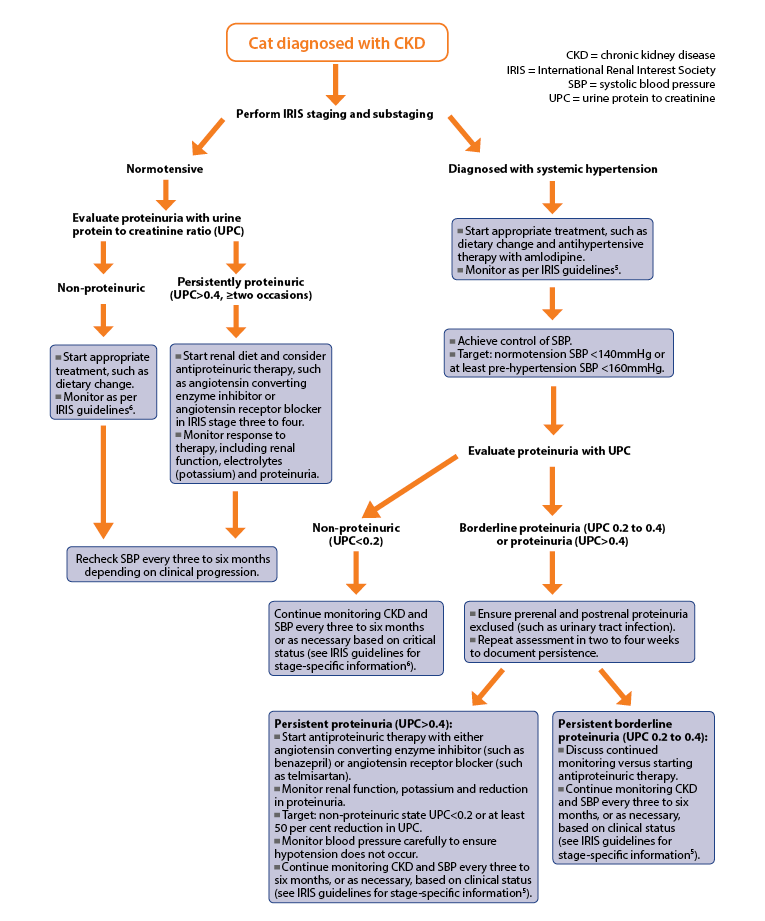

A significant reduction in proteinuria was seen in cats treated with amlodipine besylate – median reduction in UPC 0.12 (25th percentile 0.32, 75th percentile 0.50) – and only 12% of cats demonstrated an increase in UPC more than 0.1 when started on amlodipine besylate (Figure 2)3. Therefore, for cats with CKD and systemic hypertension, it may be beneficial to wait until after control of hypertension before assessing proteinuria, as many cats will become non-proteinuric once their blood pressure is controlled (Figure 3).

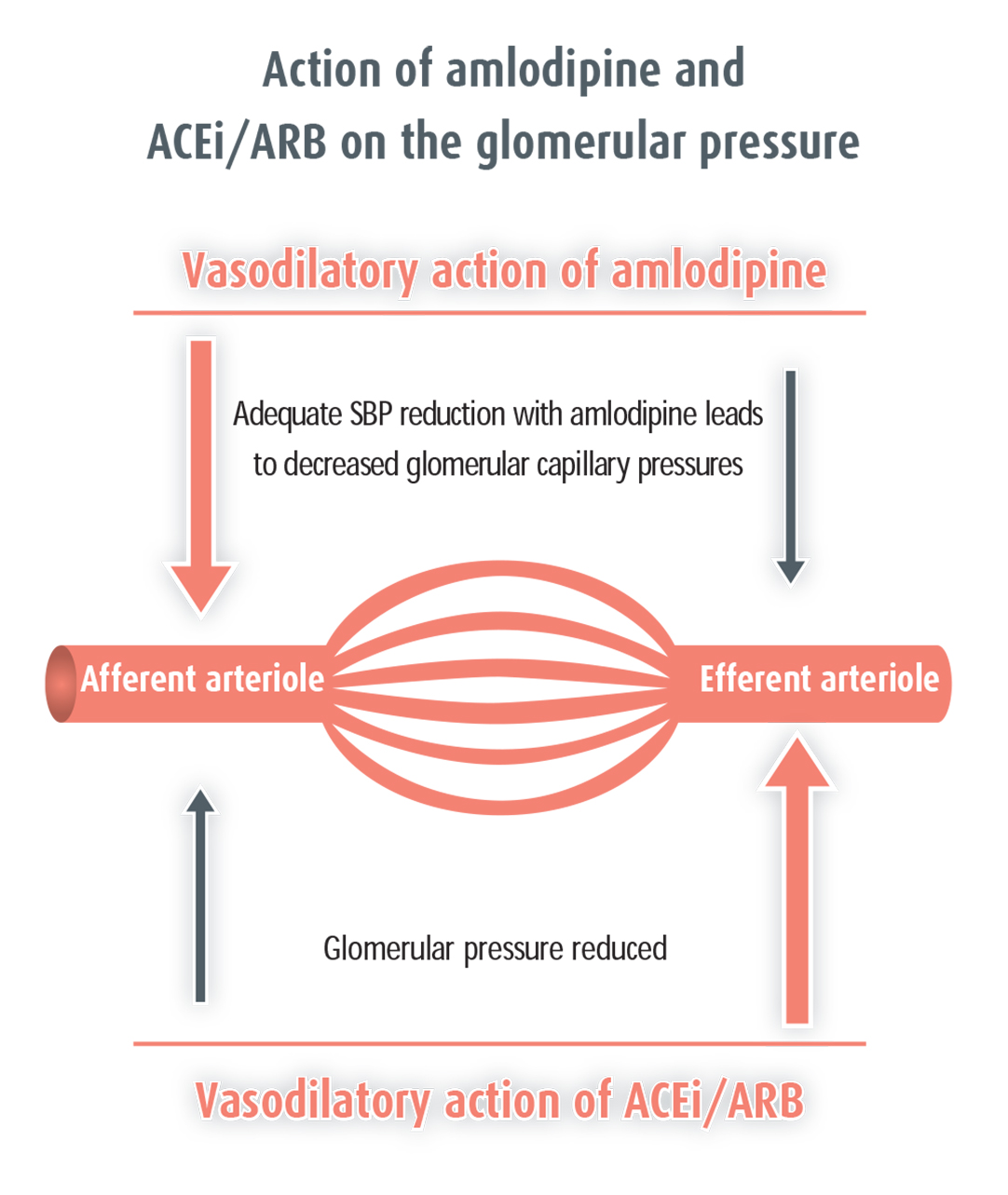

Administration of amlodipine results in afferent arteriolar vasodilation. Marked reduction in systemic pressure, which are usually in the magnitude of 40mmHg to 50mmHg in the cat, translates to reduced glomerular capillary pressures. Reduced glomerular capillary pressures aid in reduction of proteinuria without impact on GFR and plasma creatinine concentration.

Administration of an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) results in preferential dilation of the efferent arteriole, reducing glomerular capillary pressures and proteinuria. A small reduction in glomerular filtration rate will also be seen.

For cats that remain proteinuric despite good control of their blood pressure antiproteinuric therapy should be considered. The recommendation from the IRIS is specific antiproteinuric therapy should be started for cats with UPC remaining persistently more than 0.4, although a trend for some clinicians is to treat cats in the borderline category (UPC 0.2 to 0.4)6.

Renal function for cats in IRIS stage one, two and three should be carefully monitored when specific antiproteinuric therapy, including ACEis, such as benazepril, or ARBs, such as telmisartan, is started in case of decline in renal function. ACEi and ARB therapy should not be started if concern exists about dehydration or hypovolaemia until fluid status is corrected in any stage of CKD. The use of ACEi or ARB in cats with IRIS stage four CKD should be done with extreme caution and their use is considered contraindicated in this stage by many clinicians.

Moreover, both ACEis and ARBs are known in human medicine to act on blood pressure due to their effect on angiotensin II production and inhibitory action at the angiotensin I receptor, respectively.

In cats, ACEis, such as benazepril, have poor antihypertensive action and, therefore, should not be used as a single agent for the control of blood pressure. However, they are typically well tolerated in combination with amlodipine besylate for the combination of antiproteinuric and antihypertensive actions, respectively.

Data indicates telmisartan has antihypertensive effects in cats15,16. Concurrent use of telmisartan and amlodipine has been reported in a limited number of cats and been well tolerated, with telmisartan used at its licensed antiproteinuric dose11. However, extensive use of this combination of drugs has not been studied and careful blood pressure monitoring is warranted when telmisartan and amlodipine are used in combination in case of the development of hypotension (Figure 3).

Prognosis of systemic hypertension and CKD

Only one study that has specifically evaluated the survival of cats with systemic hypertension3. In this study, proteinuria was the only significant risk factor associated with survival both at the time of diagnosis of hypertension and after treatment.

It can be speculated that control of proteinuria may be an important secondary end point in the management of systemic hypertension, but further study is needed to evaluate whether more stringent control of proteinuria results in survival advantage in hypertensive cats with CKD.

For cats with hypertension and CKD that are identified to be either borderline proteinuric or proteinuric, administration of amlodipine is successful in reducing proteinuria in some of these cases. Future work should focus on the optimal way to manage those cats that remain proteinuric despite optimal control of SBP with amlodipine.

Conclusion

In conclusion:

- Systemic hypertension is common in older cats and those with CKD.

- Monitoring blood pressure should be routine for all cats diagnosed with CKD.

- Careful communication helps owners understand the importance of BP measurement.

- Monitoring SBP allows an early diagnosis of hypertension to be made, reducing the risk of significant hypertensive TOD.

- Cats diagnosed with CKD should be staged according to IRIS6 and sub-staged for both blood pressure and proteinuria.

- Cats with CKD and hypertension are often more proteinuric than normotensive cats.

- In hypertensive cats it may be worth waiting to assess proteinuria until BP is controlled.

- Many cats with hypertensive CKD will show a reduction in proteinuria once their blood pressure is controlled.

- Antiproteinuric therapy should be considered for cats that remain proteinuric after control of blood pressure.