5 Feb 2025

Figure 1. Pain pie concept. Image: © Emily Saunders

Feline acute pain expressions are subtle, species specific and have long been misunderstood, yet the assessment of pain is the primary step in creating a successful treatment plan.

The roll-out of validated pain scoring systems has greatly improved our understanding of acute feline pain in the clinical setting and encourages that an adequate pain management plan relies on competent assessment.

Although these systems are well known, they are not always adopted consistently in practice and serve the potential for care-givers to overlook important pain signals outside of a numerical score (Marangoni and Steagall, 2024).

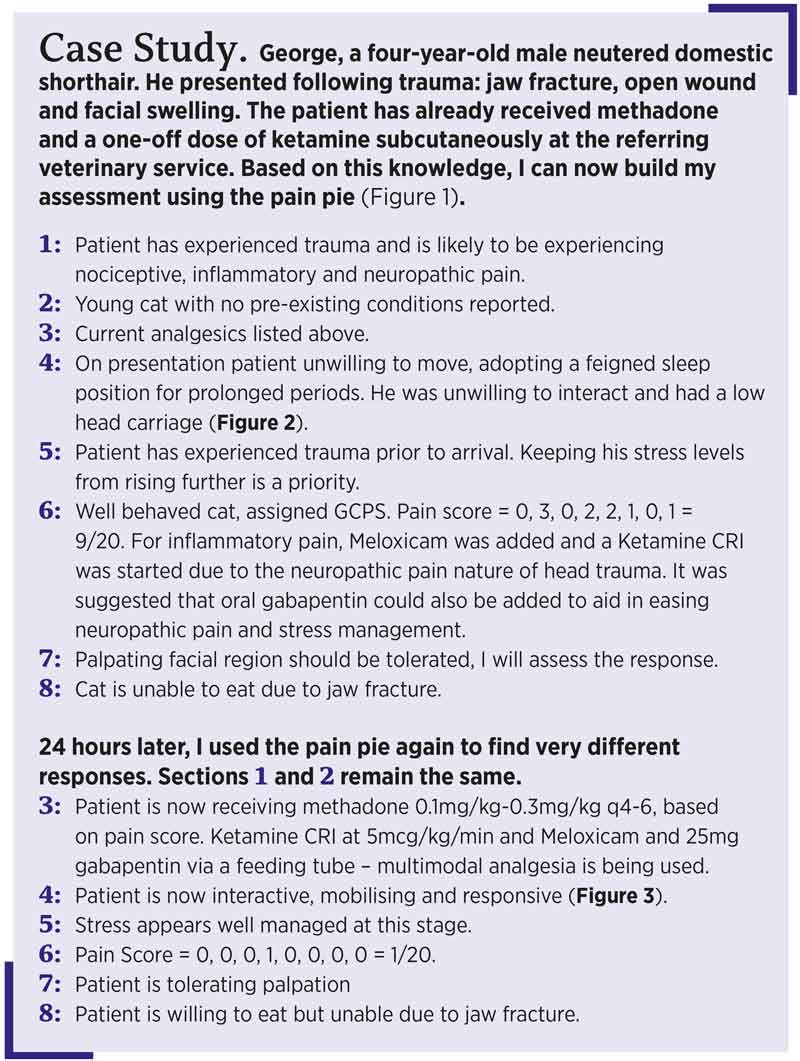

The Happy Catty Pain Pie is about more than pain scoring, ticking a box or quantifying pain. It is about assessing our feline patients holistically.

The eight-part pain pie is a tool for educating about feline pain behaviours and encourages an assessor to think about aspects of validated pain scoring systems, as well as thinking beyond, before obtaining a value and communicating with the respective veterinary surgeon about analgesic options. My aim is to broaden the horizon of what to acknowledge in our feline patients’ pain status, as well as to empower advocacy in their care.

Pain should not be judged only on how it feels, but about how it makes a patient feel. Previous significant experiences can alter how a patient perceives the pain they are experiencing. Memory, fear and stress can all credit towards an increase or decrease in this perception and, therefore, the final response (Monteiro et al, 2022). Managing pain is not only about providing analgesia – the mental welfare of the patient must also be considered and respected (Steagall et al, 2022).

Our current, most commonly used options for pain scoring are the Glasgow Composite Pain Scale (2014) (GCPS) and the Feline Grimace Score (2019) (FGS). Both generate a numerical value, with some similarities in assessing facial features, with the FGS adopting a more “hands off” approach. Although validated, these acute pain assessment systems are subjective and open to bias (Steagall et al, 2022).

All of our patients will present with a primary condition or reason for admission. One should first consider the nature of any disease or condition and whether this has associated pain. If the reason for admission is elective surgery, then step one of the pain pie will only apply post-surgically, but if the condition is traumatic or medical, the pain pie asks the assessor to consider pain and its origin.

Second, the assessor will consider any pain related to pre-existing conditions. For example, the patient may have osteoarthritis or dental disease, as well as the primary condition. Pain is personal and is categorised into different types. There is a tendency to blanket term pain and treat with little thought to the type of pain being experienced. This is where education on multi-modal analgesia is important, to ensure that different stages of the pain pathway are being targeted. The pain pie considers acute versus chronic pain and neuropathic, inflammatory or nociceptive pain.

When I meet a new patient that requires a pain score, I always consider what analgesia they are already receiving. For example they may be on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at home or received gabapentin prior to admission. Perhaps they are already hospitalised and this is the first time that I am meeting them.

At this point we can start to think about building a multi-modal analgesia plan and exercise advocacy and pharmacological knowledge. This may include local anaesthetics alongside systemic drugs, as well as considering the efficacy and duration of the analgesics being chosen. Within the treatment plan, non-pharmacological options such as comfortable bedding, cold therapy and feline-friendly handling are also elements of pain relief (Steagall et al, 2022).

In 2023, an ethogram study was conducted to widen the understanding of feline behaviours associated with acute pain. A unanimous agreement was made that behaviours such as lack of interaction and investigatory behaviours, hiding in the back of the kennel and feigned sleep were all suggestive of the presence of pain.

Behaviours such as laying in a dorsoventral position, withdrawing from the observer and no interest in food or their surroundings may also relate to pain (Marangoni et al, 2023). Although attention to body language is already included in both GCPS and FGS, it is important to consider the new research and if your patient is disinterested or hasn’t moved all day, they may need further assessment.

Stress has a huge impact on the perception of pain, but is not part of any pain scoring system. Cats have an exceptional memory and this tool addresses the individual experience and needs based on past and present exposure to the hospital.

Cats that experience a similar surgical procedure or are represented with a familiar stressful environment, may experience variable levels of pain and response to analgesics. (Marangoni and Steagall, 2024).

If a patient had been labelled as aggressive, perhaps this is genuinely part of the cat’s personality or perhaps it is a fear, self-defence or pain response driven aggression (Steagall et al, 2022). Monitor this patient’s behaviour and ensure that you have taken steps to reduce stress.

Pain score

Pain scoreIn practice, I exercise the use of both the GCPS and the FGS, allocating the most appropriate to the patient upon admission, remaining continuous throughout their hospitalisation. An article by Watson (2024) discusses areas of feline anatomy that when touched may create a negative response, regardless of pain.

For more easily agitated patients, I may opt for the FGS as it applies a hands-off approach to avoid an inaccurately high numerical pain score. Watson proposes that if a painful region is to be palpated it should be done last and with a degree of caution to exaggeration.

Additionally, the pain pie includes a section on appetite. For a cat to want to eat, any stress or pain should be well managed. Nutrition is a crucial tool in effective healing and a cat in discomfort is unlikely to eat (Taylor, et al, 2022). It is worth considering allowing the cat time to eat without a buster collar or in private and where possible pain scores should not be performed while the patient is eating, sleeping or grooming (Steagall et al, 2022).

The benefit of using any pain scoring system is that it encourages a consistent and structured approach to pain assessments, with objectives. The reduction of pain in our feline patients is beneficial to their recovery time and overall welfare, but it also impacts the veterinary professionals.

Reduced pain and stress in our patients reduces stress in the workplace, improves safety, pride and job satisfaction. The use of the pain pie will encourage care-givers to recognise the finer details, identify pain with ease and establish response to the analgesia plan.

Applying the pain pie may reduce confusion around drug-induced dysphoria, a limiting factor of scoring systems (Steagall et al, 2022). It may also clarify falsely high pain scores associated with behavioural or environmental influences now that elements such as stress have been considered.

Most importantly, the use of this visual tool for educating about feline pain behaviours will encourage the delivery of greater nursing care and inspire all generations to advocate for comprehensive feline pain management.

Resources available at: https://happycattypainpie.etsy.com