23 Feb 2021

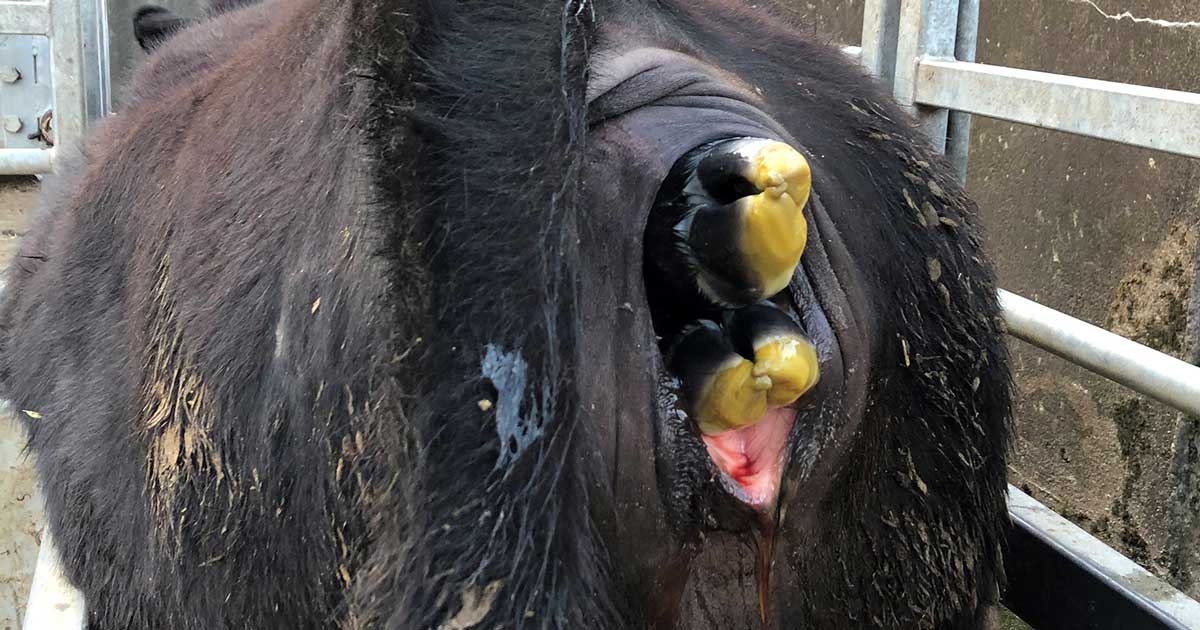

Figure 1. Classic presentation with fetomaternal disproportion.

Historically, vets do very little on suckler farms beside the traditional emergency work of calvings, prolapses and the odd sick calf – often due to the perception that the vet is too expensive to justify when the margins on suckler farms are so tight.

However, these herds present excellent opportunities for vets to become more involved, providing you can demonstrate good value, and ultimately lead to increased productivity and efficiency.

Other than hitting the desired specifications for their produce, producers have very little control over the price they are paid. Fixed and variable costs can be managed (within reason) and the farm should make concerted efforts to get these under control, but this will vary significantly between farms.

The area to focus efforts – and especially our efforts as vets – is, therefore, to improve efficiency on farm, which will ultimately lead to increased performance and production. This is especially important as the UK leaves the Common Agriculture Policy and subsidy payments to farmers are set to change.

There is one catch-all figure for suckler production: kilogram of calf weaned per cow put to bull. This incorporates bull, cow or heifer fertility and calving outcomes, together with neonatal health, and calf growth rates and performance. Each of these areas provides the vet with significant opportunities to engage with the farmer, increase the farm’s efficiency and, ultimately, improve profitability.

The first step to maximising “kilogram of calf weaned per cow put to bull” is to avoid a high barren rate.

The target pregnancy rate is greater than 95% (Table 1) over a nine-week breeding block, which will be influenced by bull and cow or heifer fertility. Bulls are rarely infertile, but many are sub-fertile, reducing their serving capacity and the number of calves born. The bull breeding soundness examination (BBSE), including semen analysis, is a crucial tool to detect these sub-fertile animals, allowing action to be taken to prevent problems and poor performance.

| Table 1.Industry key performance indicator targets (Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board, 2019) | |

|---|---|

| Industry target | |

| Calves born per 100 cows/heifers put to the bull | >95% |

| Calves weaned per 100 cows/heifers put to the bull | >94% |

| Cows calving within first three-week period | >65% |

| Mature cows with assisted calvings | <5% |

| Age at first calving | 24 months |

| Calving period | <12 weeks |

| Empty cows | <5% |

| Calf mortality – during pregnancy | <2% |

| Calf mortality – birth to weaning | <3% |

The BBSE is not without limitations, however; physical mating or mounting ability is rarely assessed, and some bulls can yield a poor-quality semen sample when electroejaculation is used (the most common collection method employed).

In 2019, the author’s practice found 16% of all bulls examined to be unsuitable for breeding, most of which were pre-sale assessments. Others typically report 20% to 25% of bulls examined to be unsuitable (Carroll et al, 1963; Kennedy et al, 2002). Proven bulls should be checked every year and not simply relied on to work because they have done in the past; however, convincing clients to do this is difficult.

Farmers should aim for single sire mating without swapping. Swapping or rotating bulls is commonplace, however, “in case a bull is not working”, but this is grossly inefficient when you consider the cost of the bull.

With all things considered – purchase price, and fixed and variable costs, minus the cull value that is typically returned at 5.8 years of age after 4 years of service (Penny et al, 2001) – it is estimated that a bull will cost £1,660/year. If this bull sires only 30 calves then he costs £55/calf born. On the other hand, if he sires 50 calves then the cost is significantly reduced to £33/calf. It is, therefore, far better to have fewer bulls that are known to be fertile and reduce costs.

A typical bull to cow ratio is 1:40 to 1:60; however, this should be reduced if the breeding females have been synchronised, while fertile bulls can cope with an excess of 1:60. A ratio below 1:40 is likely to lead to boredom and fighting among bulls if they are mixed with a larger group of females, ultimately reducing pregnancy rates.

For small herds, the use of AI may be more appropriate than keeping a bull – both in terms of cost, but also from the point of view of safety. AI also has an advantage of (usually) providing access to superior genetics, so it should not be completely discounted by enterprises of any size.

The major disadvantage of AI, however, is that the farmer will have to perform heat detection, invest in detection systems or synchronise breeding females and perform fixed time AI. Clients should be well informed of all these options, together with the relative costs and benefits.

Cows should maintain a body condition score (BCS) of 2.5/5 to 3/5 for optimum fertility and milk production. The health status of the herd should be known, with appropriate vaccination protocols in place if required against the usual suspects of bovine viral diarrhoea, infectious bovine rhinotracheitis and leptospirosis before mating. Any parasitic disease should be treated.

Trace element status should be known and action taken to address any deficiencies, with particular attention to iodine, selenium and copper. These can affect both conception rates and the parturition process, together with calf vigour and viability at birth.

There should be consideration of the forage provided to breeding females – for example, brassicas, which are used as an outwintering feedstuff, are well known to be low in these trace elements. Again, this all provides plenty of opportunity for the vet to engage with the beef suckler farm.

Breeding females should be pregnancy diagnosed (PD’d) as a minimum one month after the breeding block concludes, which provides another opportunity for vet involvement. It can be beneficial, however, to PD all the females around 50 days after the first day of breeding. This will allow detection of all pregnancies to the first oestrus cycle and provide a clue as to how breeding is going.

Any empty animals can then be PD’d again one month after the conclusion of the breeding block. The major disadvantage to this is the need for extra handling and additional cost to the farmer.

Maintenance costs for a suckler cow are £450/year to £800/year (Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board; AHDB, 2019). It is, therefore, imperative that suckler cows are PD’d so that barren cows can be sold by the farmer. A simple cost/benefit analysis is shown to this effect in Table 2. If barren rates of greater than 15% are identified then Campylobacter fetus should be considered.

| Table 2. The economic return from pregnancy diagnosing and subsequently selling any empty cows that would be expected with differing conception rates. The cull price is the four-year average from Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board Markets, correct as of September 2018 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of empty cows (per 100) after 9-week breeding period with different conception rates (CRs) | Number of empty cows (per 100) after 12-week breeding period with different CRs | |||||||

| Cost of scan/cow | Cost of scan/100 cows | Slaughter value of 600kg cull cow at average price (£1.20/kg) | 60% CR | 50% CR | 40% CR | 60% CR | 50% CR | 40% CR |

| £3 | £300 | £720 | 6 | 13 | 22 | 2 | 6 | 13 |

| Total income from slaughter of all empty cows as cull cows | £4,320 | £9,360 | £15,840 | £1,440 | £4,320 | £9,360 | ||

| Net profit from scanning (income from slaughter minus cost of scanning) per 100 cows | £4,020 | £9,060 | £15,540 | £1,140 | £4,020 | £9,060 | ||

Increasing the number of calves reared per 100 cows put to the bull by just 2% could increase calf sales by £1,000 to £1,200 per year (AHDB, 2019). A high health status is important to avoid infectious abortion prior to calving, together with minimising stress and providing suitable nutrition to prevent non-infectious abortion.

It is imperative to ensure little perinatal mortality – often caused by dystocia – which is more common in heifers than cows. The often-quoted target figure for perinatal mortality in suckler herds is less than 2%, yet it appears that this target is rarely met (Caldow et al, 2005). A recent study in Orkney found an average perinatal mortality rate of 5.1% (range 1.6% to 12.4%) in suckler herds (Norquay et al, 2020).

Pelvic measurement of heifers, together with an ultrasound examination of reproductive tract prior to breeding, allows for an assessment of their breeding viability (Hull, 2019). By identifying those heifers with a small or abnormally shaped pelvic area, they can be removed from the herd and fattened to reduce the incidence of dystocia.

Fetal size is more important in determining dystocia than pelvic area, so we cannot use pelvic measuring to fully predict dystocia; however, it has been shown that greater rates of dystocia exist in heifers with a small pelvic area (Troxel, 2011). Pre-breeding assessment of heifers, including the measurement of pelvic area, presents a good opportunity for vets to positively engage with their clients.

High energy density feeds should be avoided for the final trimester of pregnancy. Excessive energy intakes at this time will result in excessive growth of the calf in utero, together with a gain in BCS and fat being laid down in the internal pelvic area, all increasing the risk of dystocia (Figure 1).

Besides dystocia, fat cows are also more likely to suffer from uterine inertia, reduced dry matter intake around calving and metabolic issues, and subsequent postpartum diseases such as retained fetal membranes, endometritis and anoestrus activity, increasing the risk of a future barren cow (Potter et al, 2010).

Reducing neonatal mortality (24 hours – 28 days) is the next step in ensuring good weaning rates. The crucial step here is ensuring prompt and adequate intake of colostrum, both in terms of quantity and quality. This cannot be overstated.

Prevention of scour and pneumonia through rigorous hygiene measures and vaccination, where appropriate, is key both in terms of reducing mortality, but also in maximising performance by ensuring optimal weaning weights. Calves should achieve growth rates of at least 1kg/day.

To do this, it is important to prevent disease in the cow, while providing good-quality feed to ensure sufficient milk production. Ensuring a tight calving block and maximising births towards the start of the calving block will also increase weaning weights, simply by giving the calves longer before weaning: this brings us full circle back to bull and cow/heifer fertility.

Increasing weaning weights by 10kg for every calf would increase output by almost £2,000 on a 100-cow herd (AHDB, 2019).

A tight calving block is also advantageous for managing farm labour, as all calving and management procedures, such as disbudding and vaccinations, can be performed more efficiently in a concentrated pattern.

It is also advantageous with regard to disease; calves will be of a similar age, reducing disease that could otherwise spread from older animals to younger and more susceptible animals. Finally, a tight calving block produces a uniform group of animals that is easier to sell.

Suckler farmers should look at spending money on the vet as an investment, not a cost. Assuming you can offer all these services listed and lead to positive change, increased efficiencies and an improvement in “kilogram of calf weaned per cow put to bull” then you certainly would be an excellent investment.