23 Feb 2021

Image: © SGr / Adobe Stock

As part of a summer research project at the University of Glasgow, we interviewed a number of clinicians about their preferences for failure of passive transfer (FPT) testing in dairy calves.

We had several hypotheses before we started this work, including:

Neonatal calves need to ingest between 10% and 15% of their bodyweight in colostrum of adequate quality (more than 50g/L Ig) within 6 to 12 hours of birth for immunity to be conferred via a process known as passive transfer (Weaver et al, 2000; Godden, 2008). Passive transfer is generally considered adequate if the concentration of IgG in serum is higher than 10g/L at one to seven days of age (Godden, 2008; Beam et al, 2009).

FPT is associated with increased incidences of calfhood morbidity and mortality in both dairy and beef calves (Tyler et al, 1998; Hogan et al, 2015). FPT has also been linked to long-term detriments, including:

Passive immunity is assessed either by directly measuring, or indirectly approximating, calf serum IgG concentration in the first one to seven days of life (Buczinski et al, 2018). Tests for FPT may be conducted penside, in an internal clinical laboratory or externally in a commercial laboratory setting.

Radial immunodiffusion (RID) tests, ELISAs and turbidimetric immunoassay tests all measure IgG concentrations in serum directly.

RID is considered the reference test, measuring IgG directly in serum (Cuttance et al, 2017). It is a time-consuming and expensive test, requiring specialist equipment and trained laboratory technicians to measure and plot zonal diffusion rings; therefore, indirect estimations of serum IgG are favoured.

ELISA and turbidimetric immunoassay tests are another direct way of measuring circulating IgG. These have been suggested as alternative reference tests that may reduce costs and time (Zakian et al, 2018, Cuttance et al, 2019).

In addition, IgG concentration in calf serum may be estimated indirectly.

ZST has been anecdotally favoured due to availability and cost, and is still the test offered at Scotland’s Rural College and used regularly by Scottish clinicians. It is a simple and cheap test, requiring only basic equipment and a few reagents.

The test may produce unreliable results due to the concentration of the test solution, the length of time in which the reaction takes place, the wavelength of light used to read the results, the sample itself being haemolysed and the sample having a different ambient temperature to the solution (Hogan et al, 2016). ZST has also been characterised by reagent instability and artefact interference (Hernandez et al, 2016).

Serum total protein (TP) may be measured using optical refractometry or by the biuret laboratory method (reference method; Hunsaker et al, 2016).

Refractometry provides rapid, inexpensive and accurate results, even in uncentrifuged samples (Wallace et al, 2006), but is not suitable in sick, dehydrated or moribund calves.

Gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) is an enzyme present in high concentrations in bovine colostrum (Parish et al, 1997) and its concentration in neonatal serum rises dramatically in line with absorption of colostrum constituents (Hogan et al, 2015).

Unlike concentrations of IgG and TP, which remain relatively constant until around one week of age, GGT activity in calf serum decreases from birth (Blum and Hammon, 2000; Hogan et al, 2015).

GGT measurements demonstrate good agreement with actual IgG concentrations where the age of the calf is known (Hadorn and Blum, 1997). Determining GGT concentrations using an automatic analyser provides a quick and inexpensive test, which has flexibility in regard to sample numbers (Hogan et al, 2015).

Brix refractometry (using a handheld optical or digital refractometer) measures total solids in serum by measuring the index of light refraction (Stojić et al, 2017).

In calves aged one to seven days, 90% of TPs (and total solids) in the serum are IGs (Wallace et al, 2006; Godden, 2008).

The test is inexpensive, readily available, and robust (Stojić et al, 2017). The obvious advantage of Brix refractometry over other testing strategies is that farmers and vets can use one tool to monitor FPT and colostrum quality in a calf rearing programme (Hernandez et al, 2016).

FPT testing is used for both routine monitoring and in disease outbreaks.

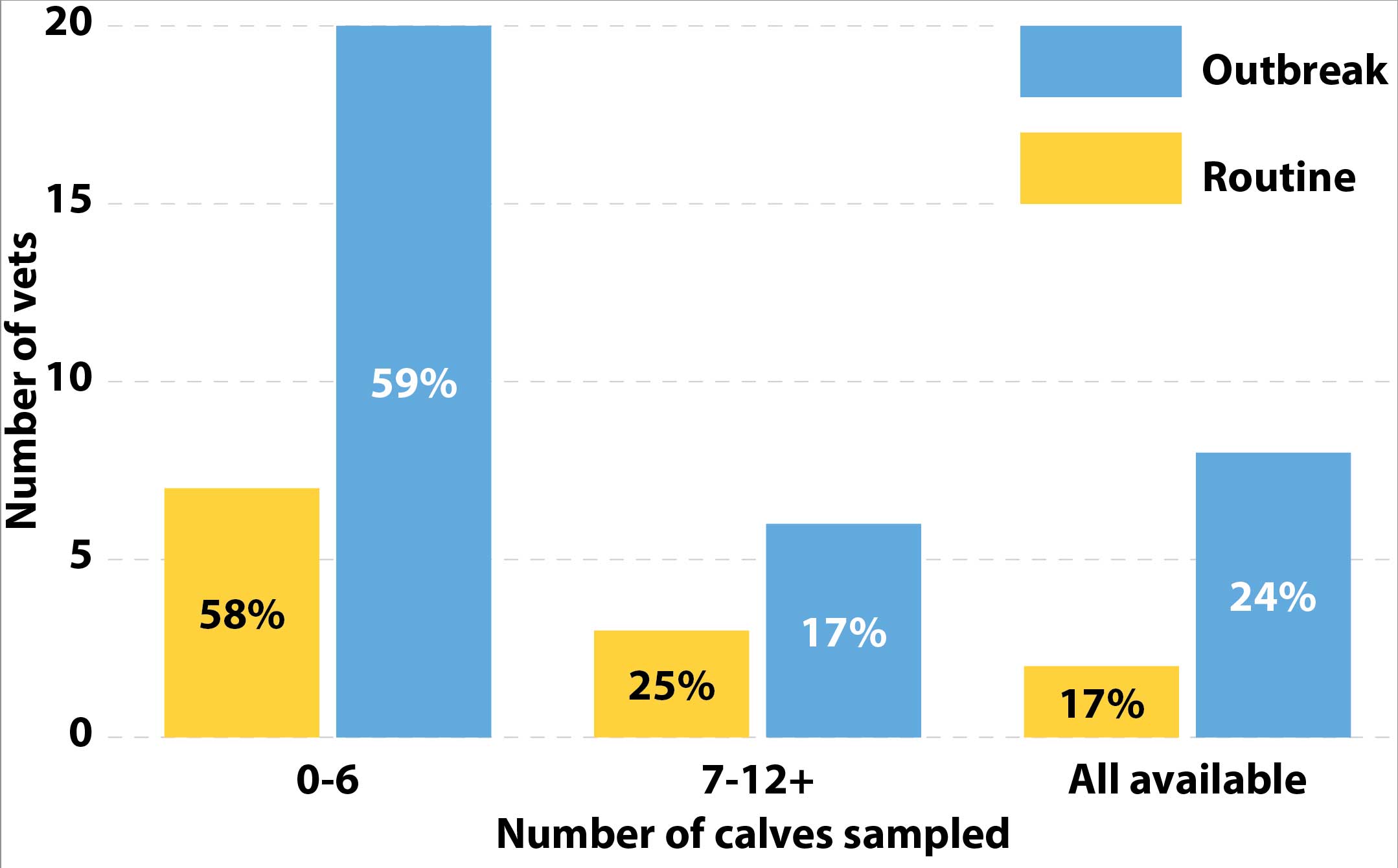

Herd-based assessment of FPT focuses on the percentage of calves that have IG levels lower than the agreed cut-point value. For this type of testing, a minimum sample size of 12 calves has been quoted (McGuirk and Collins, 2004). Sampling this number of one-day-old to seven‑day-old calves may be challenging in year-round calving systems, and several farm visits may be necessary.

Veterinary clinicians and farmers may select one testing strategy over another due to cost, availability, accuracy and previous knowledge or experience of the test. People may also be biased by their peers (for example, a new graduate vet may use the test his or her older colleagues use without much independent thought).

In June and July 2019, we conducted a survey of 34 veterinary clinicians from Stirlingshire, Lanarkshire, and Dumfries and Galloway. Seven of these interviews were conducted by telephone and 27 face-to-face.

Vets were asked:

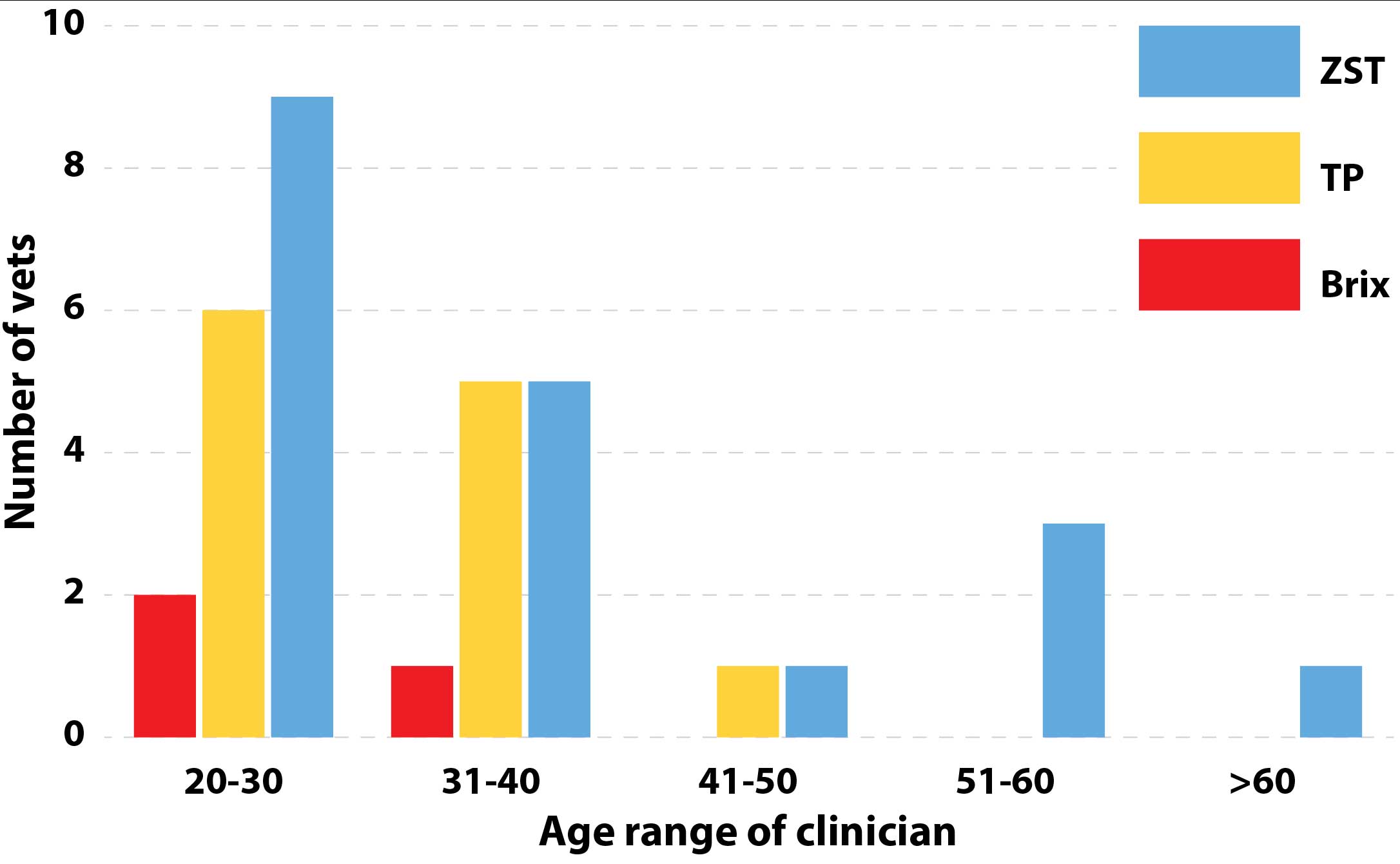

Older vets were more likely to exclusively use ZST as their first choice of testing for FPT, although the testing strategy was still used regularly by younger clinicians (Figure 1).

It was also noted that only 36.4% of clinicians were routinely testing farms for FPT. Additionally, only 25% of the vets who were routinely testing were sampling an adequate number of calve, and only 17% of vets using FPT testing in an outbreak situation were sampling an adequate number of calves (Figure 2).

Interestingly, 48.5% of the vets in this study based their choice of testing on the cost of the test, while 65% of the vets in this study agreed that availability was a factor in deciding which test to use for diagnosing FPT. Only 35% of the vets in this study based their diagnostic test choice for FPT on the accuracy of the test.

This is the first time this type of data has been collected from Scottish veterinary clinicians – and while the number of respondents was relatively low, this work provides an indication of behaviours and preferences that could be explored further.

The expense of the RID test and lack of availability of alternative reference assay in commercial veterinary laboratories is problematic in Scotland. The majority of vets in this work selected test availability over cost/accuracy, placing some responsibility on laboratories to improve the suite of FPT tests that they offer, thereby improving the accuracy of FPT diagnostics.

Younger vets’ decision-making seemed to be influenced by their older counterparts. While proper mentorship of recent graduate vets is vitally important, independent thought should be promoted and new graduates should feel comfortable to challenge the status quo.

This pilot work highlights an apparent opportunity for farm vets in Scotland to be proactively promoting routine FPT testing instead of waiting for outbreaks of disease in calves to prompt FPT testing. This commercial opportunity for a more proactive routine monitoring service should not be underestimated.

There may also be an opportunity for further education of farm animal clinicians on what constitutes a representative sample size for FPT testing in calves and on selection of the most accurate testing strategy.

Worryingly, vets in this study based clinical decision‑making on insufficient sample numbers (fewer than 12 animals). This could be reflective of small numbers of calves of the correct age range being available in year‑round calving herds.

Current research aims to describe diagnostic test preference by Scottish veterinary clinicians. As part of this research, a previous study on “hard-to-reach” farmers (Jansen et al, 2010), has highlighted a potential similarity between how farmers and vets interpret information. It this paper, it was suggested farmers could be split into four main categories of “hard‑to‑reach” farmers. These are divided into “proactivists” (outward oriented, well informed and interested in all kinds of new developments), “do‑it‑yourselfers” (active and well informed, but with a critical attitude toward external information), “wait‑and‑see‑ers” (generally open to advice from others, but rarely acted on their own initiative to search for information) and “reclusive traditionalists” (inward oriented, adverse to interference on their farms from others, with little contact with other farms and no need to compare their farm with others).

The current research speculates that when vets are both determining their choice of diagnostic test for FPT and the way in which they use it (routine monitoring versus outbreak situations only), these four categories may be mirrored – suggesting some vets will be more likely to alter their testing strategy in accordance to new published studies and in respect to their colleagues’ knowledge; whereas others will stick to the test they have always used, and will be harder to sway with increased and evolving knowledge.