25 Mar 2025

Image: Casa.da.Photo

Research into bovine mastitis is extensive and ongoing. However, articles are often published in journals, such as the Journal of Dairy Science, which incorporates many different topics. This article will summarise three articles published in the past few months of relevance to UK dairy clinicians.

Pressure has been building on the use of antibiotics in cattle, and in particular indiscriminate use of antibiotic dry cow therapy, for the past 15 years. A study led by Theo Lam from Utrecht University in the Netherlands aimed to quantify the levels of antibiotic residues in colostrum from antibiotic dry cows, and the effects on resistant populations in calf faeces1.

This was a three-part study: the first part qualified the presence, or not, of antibiotic residues in colostrum, and associations with management or cow factors. If found, the second part quantified the residues, with respect to time after calving. The third part was performed in parallel with the second, and looked at associations between those residues and extended-spectrum b-lactamase (ESBL) or plasmid-mediated AmpC b-lactamase (AmpC) Enterobacteriaceae in calf faeces.

In total, 118 self-selected farmers collected a single sample from a single cow that had been dried off with antibiotic tubes in all four quarters, with no further antimicrobial treatments during the dry period. The sample was from all four quarters as well, so taken at a cow level. These samples were frozen on farm, then sent to the laboratory for standardised testing for inhibitory substances using bacterial growth methods, and then further tested if inhibition was seen using mass spectrometry to identify the antibacterial residue present, and quantify the levels.

Seventy-five of the 118 samples tested showed the presence of antimicrobial residues – 64% (95% confidence intervals of 55% to 72%). Residues were far more likely in cows dried off with a tube containing both a b-lactam and an aminoglycoside antibiotic (83%) than with tubes containing just a b-lactam (57%); however, only b-lactams were found over the statutory maximum residue limit (MRL).

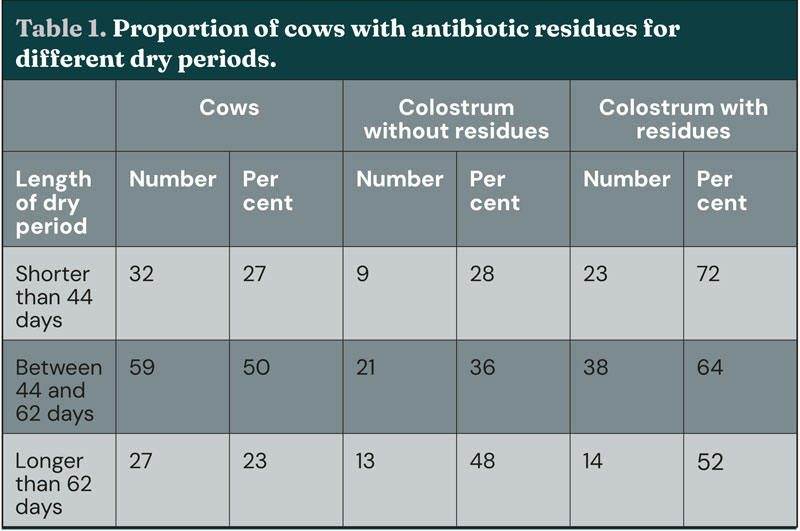

Unsurprisingly, as can be seen in Table 1, residues were more likely in cows with shorter dry periods (although not statistically significant), but still more than half of cows with more than 62-day dry periods contained detectable residues. Milk production on the day of dry off did not affect the likelihood of residues.

In the second part of the study, 28 cows were enrolled from eight herds selected on convenience. From these cows, four samples were taken from the first colostrum milking from all four quarters (first 25ml per quarter, second 25ml per quarter, third 25ml per quarter and composite from the collection bucket), with one composite sample taken from the next six milkings. All cows were milked twice a day. The samples were then tested using the same methodology as the first part.

Three of the 28 samples showed no residues at any stage. In the remaining 25 samples, no clear pattern of residue level was seen during the first milking. Residue levels for cloxacillin were noted, and a large number of samples had cloxacillin above the MRL (30 micrograms per kilogram) on the fourth milking, with two samples still above this level at the seventh milking.

In the final part of the study, 87 cows from 10 convenience-selected herds were enrolled. For each cow-calf pair, colostrum was sampled from the first collection and the subsequent four milkings.

Faeces was collected from the calf on the day of birth and both 7 and 14 days later. The first colostrum sample, and a volume-adjusted composite of the next four milkings, was tested for residues using the aforementioned methodology. Both colostrum samples, and the three faecal samples, were then tested for the presence of bacteria expressing either of the aforementioned antibiotic residence genes listed. Fifty-eight of the cows had received cloxacillin as dry cow therapy, whereas the remainder received no antibiotics at dry off.

Two of the colostrum samples showed the presence of ESBL or AmpC, with the faeces of the related calf also positive.

In total, 44% of the calves showed presence of ESBL/AmpC in at least one of the three faecal samples. Interestingly, no association was seen between either being dried off with antibiotics or the presence of antibiotic residues in colostrum with the presence of antibiotic resistance expression in calf faeces.

The summary of this paper is that, while it is clear the use of antibiotics at dry off leads to an increased presence of antibiotic residues above the MRL in colostrum, in some cases out to the seventh milking, this does not appear to lead to an increase in antibiotic resistance expression in calf faeces. The rate of antibiotic resistance expression in calf faeces is higher than would be expected, but increasing use of selective dry cow therapy does not appear to reduce the risk of resistance proliferation in calves.

Nina Lind from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Upsala, Sweden led a study that set out to investigate the link between clinical mastitis and farmer well-being2. The prediction was that farmers’ perception of illness (subclinical mastitis in this case) would mediate the relationship between the actual animal health and the farmers’ well-being, while also affecting the farmers’ perceived self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a function of the feeling of control as well as a coping strategy related to increased well-being. This study used data previously collected via farmer questionnaires as part of a larger study.

A random selection of 1,200 of the 4,039 registered dairy farmers in Sweden were invited to complete an online questionnaire between April and June 2016. Farmers were also provided with a hard copy version if they were unwilling to complete the online version.

The results were anonymous. With 356 completed, usable responses were collected, for which each farmer received two lottery tickets as a token of appreciation.

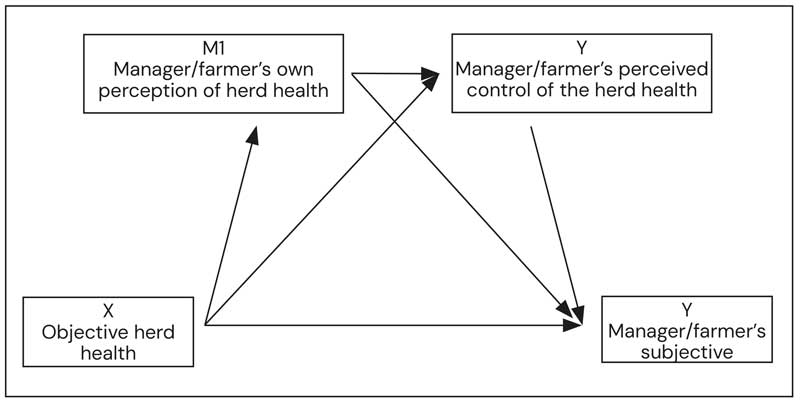

The study used a number of complex adaptations to convert the results into smaller variables (Figure 1):

Average bulk milk somatic cell count (BMSCC) was used for objective herd health (X)

Satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) has been used extensively as a measure for life satisfaction and is based on five questions answered on a seven-point scale (Y)

Farmer’s own perception of herd health was a single item on the questionnaire (M1)

Mastitis prevention self-efficacy scale (MPSES) is well described, and based on 10 questions describing farmers’ feeling of confidence about their control of preventing mastitis, reducing the incidence of mastitis and controlling the situation on farm (M2)

This allowed the relationship between X and Y to be investigated, in the context of the moderators M1 and M2. Covariates were also analysed: herd size, percentage contribution of the dairy to household income, marital status, cohabitation, farmer age and gender.

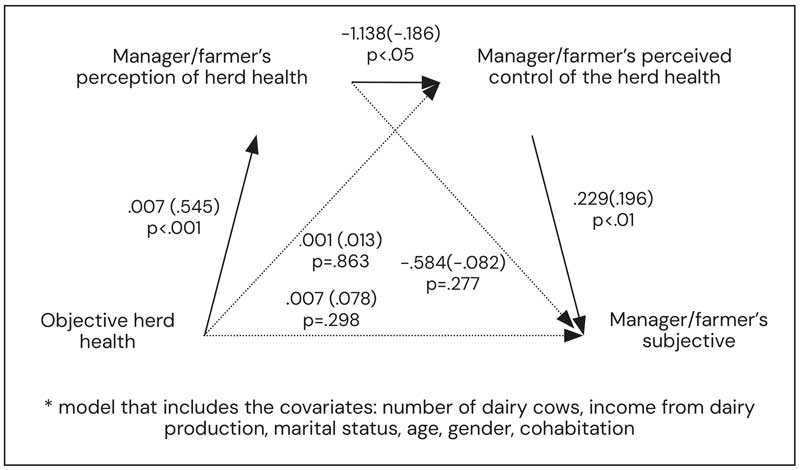

The results are really quite interesting. The study did not identify a direct link between the objective herd health (as demonstrated by BMSCC), and the well-being of the farmer (SWLS). However, there were strong links between the farmers’ perception of herd health M1, via the perception of control M2, and the SWLS. The objective herd health X also influenced the farmers’ perception of herd health M1, but not significantly the perception of control.

The largest association with farmer well-being was the perception of control over herd health M2, with a p value less than 0.01. This is summarised in Figure 2, with line thickness representing the level of statistical significance and the figures indicating the coefficient of variability (standardised in brackets).

For clinicians on the ground, the relevance of this is significant. Specifically, when farmers feel more in control over managing mastitis on their farms, both their well-being and animal health outcomes may improve. Marrying farmer perception with objective herd health is also an important moderator of the relationship.

The third paper published is from Kirby Krogstad at Michigan State University3. This paper looked at measures to assess nutritional success around transition, and their association with disease, including mastitis. It is a really interesting paper that warrants reading.

Records were assessed from one dairy herd in Michigan using an automated milking system. This provided information to assess the success of individual animals around transition, specifically body condition score (BCS), both pre and postpartum, change in BCS (DBCS), blood beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) and hyperketonaemia.

The outcome measures that were considered were conception rate (pregnancy per AI), pregnancy loss post-diagnosis, clinical mastitis cases, milk yield and the risk of leaving the herd. Between 628 and 956 cows were recording, depending on the risk factor.

No increased risk of mastitis associated with a low BCS, or a high DBCS, was seen. However, hyperketonaemia, defined as a BHB of at least 1.2mmol/L, was associated with a 34% greater risk of getting mastitis in the first 300 days of lactation. That is to say that skinnier cows or cows losing a significant amount of weight around calving were not necessarily at greater risk of mastitis, but when that animal is not coping with the energy deficit as demonstrated by excess ketone mobilisation, which affects the ability to prevent mastitis.

Much more information regarding other risk factors associated with BCS is listed in the paper; the key points are as follows:

Being thin (BCS lower than 3.25) prepartum increases the risk of premature culling by 48%

Thin cows (BCS lower than 2.75) postpartum is more significant, with an odds ratio of 2.16.

Losing at least 0.75 points of body condition is associated with a five-times higher risk of pregnancy loss, and are nearly twice as likely to be culled.

This data should come as no surprise, and reinforces the importance of transition period success, especially from a nutritional perspective, in ensuring dairy cow performance.

These three papers were all published in a two-month period in the Journal of Dairy Science, and provides a brief insight into the new research readily available to dairy clinicians.