11 Jul 2016

Image: © Wikimedia Commons/Yuriy Danilevsky.

Climate change over the past few years, along with milder winters and poor hibernation techniques carried out by many owners, has increased the number of post-hibernation problems in many tortoises, especially elderly ones that have hibernated the same way for many years.

Only fit and healthy tortoises must be hibernated. This is why pre-hibernation check-ups – including a thorough clinical examination, a comprehensive chelonian blood test, and radiograph and faecal examinations – are paramount to detect whether any tortoise has a medical condition.

The most common medical problems reported last winter were stomatitis – commonly known as “mouth rot” – renal failure due to dehydration (linked to inadequate pre-hibernation preparation), non-obstructive dystocia in gravid debilitated tortoises, rat or fox attack, frost damage and anorexia (low vitamin A reserves). Most of these patients recovered uneventfully after receiving the correct treatment and owners were handed correct hibernation protocols.

This article provides a gold standard protocol to carry out a safe hibernation, including equipment, correct temperate range and length, and provides examples of the clinical conditions and treatments used in each case.

While most tortoises inhabit deserts or tropical zones, wild ones adapted to temperate climates will slow their metabolic rate to adapt to cold weather and decreased daylight hours. This process is referred to as hibernation, or brumation, and occurs naturally (Jessop and Bennet, 2010).

Keeping and hibernating tortoises in the UK is a different story. Captive tortoises must be kept at correct temperature ranges with the aid of heat lamps and UVB lights (in the daytime and night-time) to ensure an adequate development and physiology. However, many have been or are being kept using incorrect management and husbandry guidelines.

Most of these tortoises, many older than 40 years of age, have lived in gardens throughout the year at constantly oscillating temperatures and undergo hibernation periods in sheds, lofts, garages, conservatories, cellars and cold rooms in a house.

Milder winters, due to climate change over the past few years, are contributing to increasing post-hibernation complications in tortoises.

The most common complications encountered by the author in practice are detailed in this article and feature interesting case reports with great outcomes, along with detailed guidelines to prevent these complications and ensure all tortoises undergo a healthy hibernation.

All adult reptiles should be in peak condition by the start of November and undertake a pre-hibernation clinical check that would comprise of a full clinical exam, chelonian profile, ultrasound scan or radiograph examination, faecal examination and record of bodyweight. Any underweight tortoises or ones suffering from a medical condition during the year must keep active during the winter.

The author tends not to hibernate microchipped or gravid tortoises. Frye recommends preconditioning tortoises with carbohydrate-rich foods, such as winter squashes, alfalfa pellets and mixed fruits, six weeks before hibernation so there is an adequate supply of vitamin A during this period (Jessop and Bennet, 2010).

Mediterranean tortoises require a temperature between 4°C to 7°C to hibernate successfully. The easiest method to achieve this range is by carrying out the hibernation in a small fridge and placing the tortoise inside a polystyrene box. The aim is the tortoise remains asleep during this period by being placed in an environment with a constant temperature. Make sure the fridge has a thermometer attached to monitor fluctuations.

Empty the intestinal tract. Feeding needs to be discontinued a month prior to hibernation and daily baths will help in emptying the intestinal tract. Start reducing the temperature in the tortoise accommodation and, two weeks prior to hibernation, aim for a drop of 2°C per day.

Bodyweight record-keeping is paramount during hibernation. Tortoises need to be weighed weekly and if one records a 10% bodyweight loss in a week it must be woken up. If anything abnormal is reported, such as the tortoise urinates or defecates, moves or shows any problems, the hibernation should be interrupted.

The author recommends clients start hibernation mid-January and wake the tortoises up in March. Longer periods than this can cause more clinical complications once hibernation is over. In the author’s experience, Horsfield tortoises (Agrionemys horsfieldii) do not cope well during hibernation, especially in the UK.

When the hibernation has concluded, the tortoise should be brought out of the fridge and warmed to room temperature before it can be placed on the vivarium/tortoise table. Warm daily baths will help it to become hydrated and ready to start eating fresh greens. If any tortoise is showing strange behaviour or not eating a week after hibernation, an exotic veterinarian should be consulted.

Stomatitis, or “mouth rot”, is widely found among most reptiles, although it is very common in chelonians, and involves inflammation and infection of the buccal cavity where yellow diphtheritic membrane formation, dysphagia, hypersalivation, exfoliation of the skin of the head and the neck, swelling of the ventral neck and concurrent dehydration are commonly reported.

In severe cases, ocular discharge is also present. A viral infection is likely to be the cause; however, this can be reported in tortoises that hibernated with a full intestinal tract, allowing disease from the effects of putrefaction of food remnants to settle.

Three tortoises were presented to the author suffering from stomatitis soon after waking from hibernation. Due to financial constraints, a full work-up was not carried out, but all responded well to intense rehydration (including baths with reptoboost), systemic antibiosis (ceftazidime) and topical treatment (affected oral mucosa was cleaned with diluted iodine three times daily to reduce bacterial load and remove debris).

In severe cases, an oesophagostomy tube can be placed and assisted feeding can be carried out until the tortoise starts eating by itself.

Renal failure is most commonly associated with dehydration and often reported in tortoises hibernated in a garage, shed or loft and have not been monitored properly. These tortoises may keep waking up due to oscillating temperatures, using up energy while they are not consuming any foodstuffs, and will get dehydrated.

By the time they are brought out of hibernation, they will be anorexic, have sunken eyes and very dry skin, pass dark yellow or even orange urates and will not pass urine often.

Renal failure due to dehydration can be corrected with intensive treatment and stabilise over time. The author treated several tortoises with renal failure and one passed away; a radiated tortoise (Astrochelys radiata) with severe liver failure and anaemia. It was anorexic for a month prior to consultation and even if the renal function improved remarkably after treatment with allopurinol and intensive fluid therapy, the liver failure was too acute and its condition became more complicated after developing pneumonia.

Another, a Hermann’s tortoise (Testudo hermanni) with severe dehydration, overcame renal failure and within six months its kidney parameters fell into range (Table 1).

| Table 1. Sequence of blood results in a tortoise with renal failure four months apart | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Results | February | June | Normal ranges |

| Albumin | 28g/l | 25g/l | 13 to 26 |

| Total protein | 57g/l | 46g/l | 23 to 44 |

| Uric acid | 1,455μmol/l | 331μmol/l | 124 to 466 |

| AST | 97IU/l | 165IU/l | 124 to 466 |

| Creatinine kinase | 343IU/l | 118IU/l | 0 to 620 |

| Urea | 31.4mmol/l | 31.4mmol/l | 0 to 2.1 |

| Calcium | 2.65mmol/l | 2.65mmol/l | 1.65 to 3.3 |

| Phosphorus | 0.91mmol/l | 1.92mmol/l | 0.48 to 1.81 |

| White cell count | 0.9 10^9/l | 1.5 10^9/l | 1 to 4.5 |

| Haemoglobin | 11.7g/dl | 9.1g/dl | 6.4 to 15.7 |

| PCV | 36% | 29% | 17 to 42 |

| MCHC | 32.5g/dl | 31.4g/dl | |

| AST = aminotransferase, IU = international units, MCHC = mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration. | |||

All the patients showing renal disease were administered intensive fluid therapy via intracoelomic route and orally. Allopurinol, for a month initially, was added to control renal function. All the patients also received multivitamin injections and were bathed using reptoboost three times daily. To reassess the tortoises were responding, several blood tests were carried out over time.

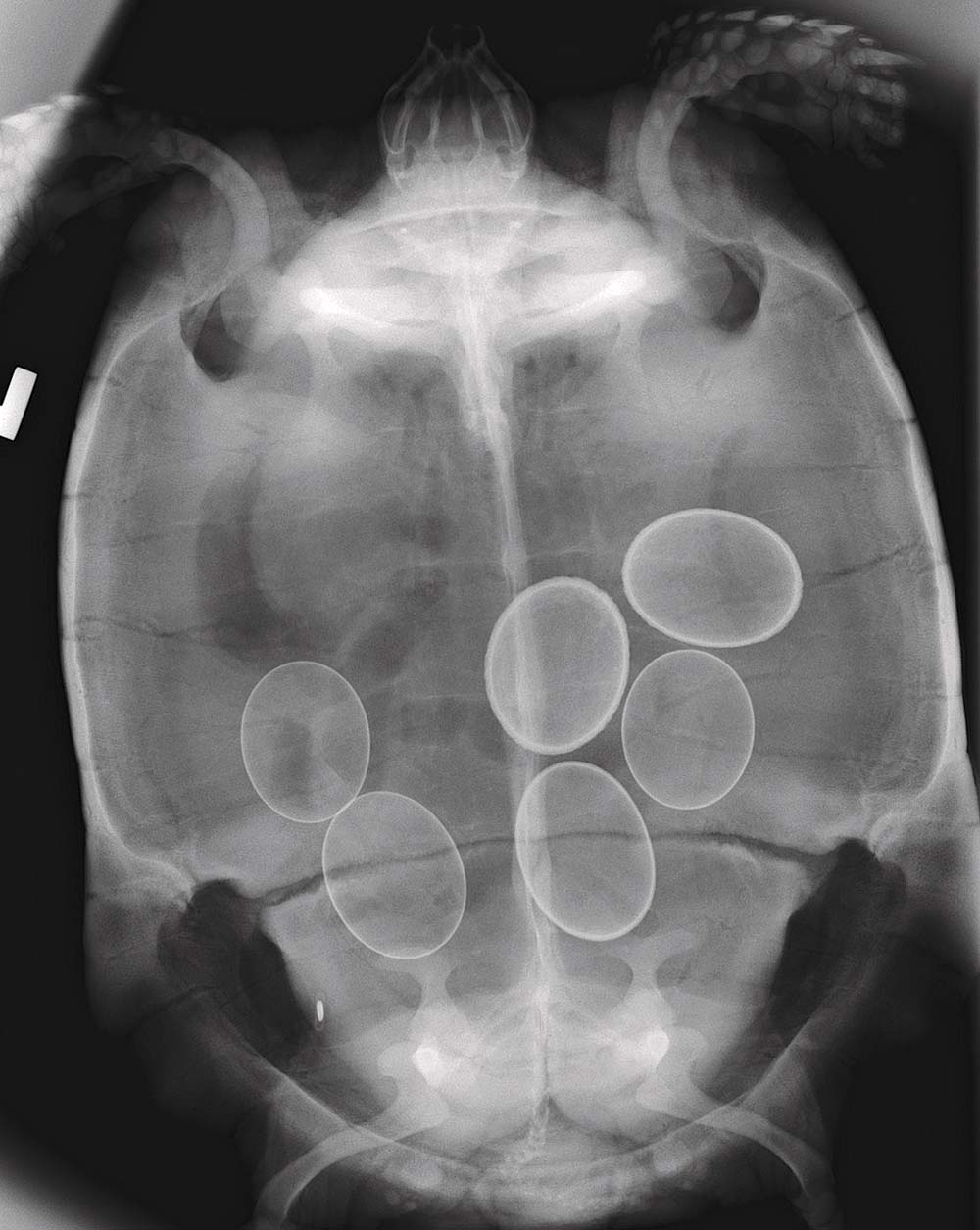

Non-obstructive dystocia was reported in seven of the author’s patients debilitated and anorexic after waking up from hibernation. All were hibernated without a full clinical and radiographic exam.

Radiograph exams revealed these tortoises were carrying eggs and started to get progressively weak. Blood tests were carried out on four of them and showed raised kidney and liver parameters, severe immunosuppression and anaemia.

Non-obstructive dystocia is linked to inappropriate husbandry, poor nutrition and unsuitable nesting sites prior to hibernation. When hibernation is not carried out correctly, the tortoise is not fully asleep and may keep waking using up energy reserves. The severity of dehydration, liver damage and severity of the anaemia varied depending on the length of the hibernation.

These patients have improved drastically. Assisted feeding via oesophagostomy tube was carried out until the tortoises started feeding by themselves. They were also supplemented with multivitamin injections at two weekly intervals and anabolic steroids (laurabolin).

Once the tortoises were fully hydrated (using intracoelomic Hartmann’s fluids and oral reptoboost), induction was started by administering calcium and oxytocin at different intervals (Denardo, 2006). Induction was successful and all passed the eggs. Six out of the seven tortoises started to self-feed within three weeks, but one of the patients was still lethargic and anorexic. Tube feeding was carried out for three more weeks. After this, an exploratory laparotomy was performed, revealing a large amount of follicles on the left ovary and ascites. The tortoise was neutered and is recovering uneventfully.

Rat and fox attacks were reported in tortoises that hibernated in sheds or garages, buried in the garden without enough insulation or a box that could protect them from potential predators.

Some of these do not successfully hibernate due to oscillating temperatures and the mutilations, in some cases, are very severe and extremely painful. Moreover, the tissues of the hibernating individual may necrotise over time, especially if the animal is not checked frequently and the trauma occurs at the beginning of the hibernation.

The author was presented with four cases of mutilation during the hibernation period. Two presented minor injuries, small bites that were easily cleaned and disinfected. The tortoises were put on a course of ceftazidime over 16 days via IM injection.

Another tortoise was found with a maggot infestation after waking as its upper tail area had been eaten away and necrotised over time. The necrotic wound was cleansed and disinfected and all the maggots were removed with forceps. Next, the wound was debrided and thoroughly cleaned with diluted iodine and the tortoise was started on a course of ceftazidime for four weeks and meloxicam for a week, with weekly check-ups. Ivermectin is toxic in tortoises and must not be used to treat maggot infestations.

The final tortoise presented to the author was severely ill. A 70-year-old female Hermann’s tortoise extremely dehydrated, very lethargic, very cold on presentation, its mucous membranes were very pale and its left forearm was almost eaten away, possibly by rodents, showing exposure of the radius and ulna bones. A full chelonian profile showed severe immunosuppression, anaemia and liver failure, renal failure and high-ionised calcium levels. A radiograph exam revealed six eggs in the coelomic cavity with thick shells indicating the eggs had been bound for a while. The tortoise was also anorexic.

In this case, the author started intense fluid therapy until the patient started to pass a good amount of urine indicating good hydration. Urine was clear, but the urates were green due to the liver failure (prolonged starvation period). Systemic antibiotics (ceftazidime IM), pain relief (meloxicam) a multivitamin injection and an anabolic steroid injection (nandrolone) were given. The author fitted an oesophagostomy tube and oxbow critical care for herbivores was fed three times a day for a week. The response was great and the patient started to gain strength, so was induced with calcium gluconate and oxytocin to help it pass the eggs.

The author managed the open wound with wet to dry bandages and Intrasite gel. The wound healed within five weeks. Antibiotics were administered for two months. A blood test two months post-trauma was unremarkable and it recovered fully. The feeding tube was removed at the same time, as the patient started to eat well.

Freeze damage to the retina can cause blindness in chelonians. Retinal damage will appear as a lack of refractivity of the fundus on ophthalmological exam. Blind animals will have a reduced appetite. Vitamin A supplementation and long-term support care may help repair the damage in some cases.

It is paramount to have an adequate control of the hibernation temperature range to prevent freeze damage and the reason the author does not recommend hibernating tortoises outdoors (such as in sheds or garages) without inadequate insulation and suggests the fridge method.

Anorexia was reported in many tortoises post-hibernation, due mainly to deficiencies in vitamin A and minor dehydration. More than 10 patients were reported anorexic on waking.

An injection of vitamin A, which can be repeated two weeks after the initial dose, and intense hydration via reptoboost baths five minutes three times a day generally helps the appetite return if no other medical problems are reported at the time of clinical exam.

The author would like to acknowledge Sue Schwar, charity founder at the South Essex Wildlife Hospital, and Amanda Britten RVN MBVNA for proofreading this article.