31 Aug 2021

COVID-19 has changed a lot in our lives and has impacted the lives of the rabbits under our care. We are also seeing many new first-time “lockdown” pet owners coming to us, and this is a great opportunity to reach them and get them in the habit of keeping rabbits in an optimal way.

We have also seen a long interruption in our ability to provide routine health care, vaccinations and advice, so we need to re-establish contact and care for our more established owners.

In short, now is a good time to review rabbit health care and how we can help owners improve the welfare of their pets.

A (rare) positive from Covid is that we now have a public who can see first hand just what benefits vaccination can bring. Combine this with the advent of a new triple vaccine for rabbits, covering both strains of rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD) as well as myxomatosis in a single annual dose, and we have a great opportunity to reverse the appallingly low vaccination rates in rabbits (see PDSA Animal Wellbeing Reports).

Perhaps even better is that we now have a range of effective vaccines for rabbits against individual pathogens as well. This enables us to give proper advice for each individual situation depending on lifestyle, disease risks and owner concerns (for example, indoor/outdoor keeping, contact with wild rabbits, boarding and so on).

While this may seem more complicated than simply giving a triple jab (which may well be the answer in many cases) and little/no evidence exists about the effects of potential overvaccination in rabbits, it is important to listen to owner concerns and mirror the risk-based approaches we take in other species. These approaches may change if lifestyle changes or if the risk alters – for example, a cluster of RHD-2 cases or if in contact with a myxomatosis/RHD case.

It is important that manufacturer advice is followed with vaccination, although a number of off-licence uses may be applicable in certain situations. If using vaccines off-licence, it is essential to obtain informed consent from the owner (Figure 1).

Although rabbits do suffer from a range of parasitic conditions, prophylactic therapies are not commonly indicated and generally should be implemented on an individual risk-based approach.

It is also worth bearing in mind that several of these issues – for example, skin/ear mites – may be a sign of underlying disease and/or immunosuppression. Prevention therefore, as ever, relies on looking after the whole rabbit.

Licensed preparations of imidacloprid are available as a spot-on for flea control. With treatments needing weekly repeats, they are not especially practical as the sole means of flea control, but are extremely effective as part of overall household flea control where an issue exists.

In terms of prevention, reducing contact with wild rabbits will reduce risk of rabbit flea infestation and good control of fleas on other pets will reduce risk of cat flea infestation.

Various mite species (including Psoroptes ear mites, Cheyletiella and fur mites) are found causing disease on pet rabbits. Ivermectin-based products are licensed for use in rabbits and are effective. However, prophylaxis is rarely needed unless a rabbit is being introduced from premises with a known issue with these parasites.

In these cases, quarantine (see further on) is indicated with prophylactic treatment during these times. In some cases pet owners may be asked to treat rabbits before entering boarding establishments.

Cyromazine (Rearguard, Elanco) is licensed for prophylaxis of myiasis and appears very effective. However, it is not the whole answer, with a big emphasis on controlling disease that affects prehension of caecotrophs (for example, dental disease, arthritis) and overall hutch hygiene to reduce the chances of flies being attracted to the rabbit (Figure 2).

Other parasites – for example, ticks and harvest mites – may be seen; prophylaxis for these can be extremely difficult as therapies may not be validated or may be toxic (for example, fipronil).

In these cases, it may be necessary to keep rabbits off certain areas of the garden for some parts of the year (Figure 3).

Endoparasite treatments are rarely needed in pet rabbits. While nematodes are found in rabbits, disease is extremely rare, so prophylactic deworming is simply not indicated (Figure 4).

Coccidiosis is seen in young rabbits and faecal screening should be performed for any rabbit showing diarrhoea, and/or wasting and illthrift. Prophylactic therapy should be given to all in-contacts and breeders should consider treating litters on premises where coccidiosis is regularly seen. Trimethoprim-sulphonamide (Sulfatrim, Virbac) is licensed for this purpose.

In refractory cases toltrazuril may be used off-licence, although dosing must be closely monitored as it has a lower therapeutic index. In all cases, rabbits should be kept off contaminated ground during therapy.

Fenbendazole is licensed for control of Encephalitozoon cuniculi in rabbits. However, little direct and non-anecdotal evidence exists of reduced incidence of actual disease in regularly treated rabbits. Merit certainly exists in treating those in contact with confirmed clinical cases of E cuniculi, although it would always be worth testing these rabbits for E cuniculi IgG and IgM antibodies before and after therapy.

Otherwise, given reports of fenbendazole toxicity in rabbits and the lack of alternative therapies for actual clinical disease, the author feels that routine regular prophylaxis is not justified, given the current knowledge base. What is worth considering is serotesting rabbits and then taking extra care with seronegative rabbits that they are not potentially exposed to disease (for example, shows, boarding and so on).

Female rabbits are very prone to uterine adenocarcinoma. As such, ovariohysterectomy is absolutely recommended in terms of prevention.

Evidence certainly suggests that tumour risk is much higher than risks from anaesthesia, but we can further affect this by making sure we perform anaesthesia in as safe a manner as possible, not just in terms of drugs, but in overall stress reduction and care through the whole day hospitalised.

Having considered the “medical” means of disease control, it is clear that drugs and vaccines aren’t the whole story. They also only address infectious disease… and non-infectious diseases are much more common.

An obvious example is diet – correct diet is essential for good health and in the case of rabbits, vital in the prevention of dental disease. A lot of data is now showing the effect of a good-quality, high-fibre diet in reduction of acquired dental disease; rabbits are designed to eat grass and hay, and need huge levels of fibre to keep the teeth correctly worn down.

Lack of fibre will also increase chances of obesity, with resultant effects on joint loading and cardiac/hepatic disease.

Correct dietary balance and fibre levels are, of course, vital in maintaining gut health, and can be a factor in those rabbits with recurrent gut stasis and/or caecotrophy problems.

Another issue is the need to provide plenty of water. Urine sludge is partly linked to reduced movement and urination (for example, spinal arthritis), but also to the amount that rabbits drink – a diet that produces large quantities of urinary crystals needs flushing through.

Research from the University of Zurich has identified that dietary calcium levels are much less significant than the amount drunk and encouraging drinking (use of bowls rather than drinkers, and providing plenty of these all round the hutch and run; wetting down green food can also help) will reduce buildup of sludge in the bladder.

Too many rabbits suffer restricted housing. As well as the restriction of normal behaviours and resultant effects on welfare, restriction will result in physical disease in terms of exacerbation of arthritic disease and reduced skeletal calcification enhancing risks of injury.

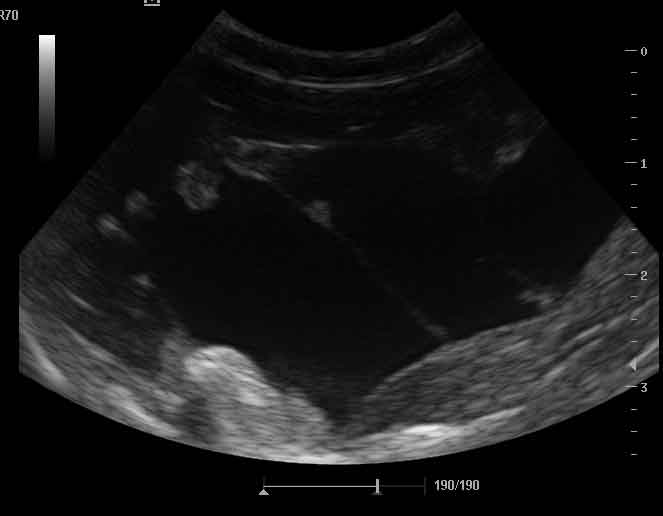

Restricted rabbits also tend to have reduced urination frequency and faecal output, so can also be more at risk from urinary sludge issues and gut stasis (Figures 5a and 5b).

Substrate is also important, with pododermatitis being shown to be more likely on substrates that are not hay or grass.

And, of course, hygiene – damp-contaminated environments may also predispose to pododermatitis and certainly encourage flies, increasing the chance of myiasis.

If hutch space is too cramped, reducing ability to groom, then caecotrophs will not be taken and the odds of myiasis rise again (and of course, digestive function will also be affected).

It’s also worth considering other physical aspects – steep ramps are not kind for older rabbits with arthritis.

In terms of disease control, we can go much further back.

Breeding brachycephalics will increase risks of dental disease and ear disease; breeding lops will increase incidence of ear disease; and breeding rabbits of extreme size will have effects on joints, heart disease and a much reduced life expectancy.

We can encourage our clients to buy rabbits that are the size and shape of, well, rabbits… and they will be more likely to have a longer-lived pet and many fewer vet bills.

To finish, the author will look at two categories that have really been brought home to us during these past months of Covid lockdowns.

The first is the need for quarantine and biosecurity. For breeders, exhibitors and rabbit boarders (and, of course, vets) biosecurity is vital. Often, the main emphasis is on disinfection, but this will not be enough without good cleanliness, and if disinfection is not done properly using appropriate agents at the correct dilution and with the correct contact time.

Another simple measure for all rabbit keepers is that of quarantine. Introducing (and reintroducing) rabbits to each other is the ideal time to introduce novel pathogens to each other – especially as often a degree of stress and immunosuppression will exist at such times.

Gradual introduction involving physical separation, but allowing sight and smell of each other for an appropriate period, will reduce disease transmission and may reduce risks of physical damage when the rabbits are mixed.

Quarantine also allows time for vaccines to be given, and to permit infectious disease testing and targeted drug prophylaxis as indicated.

Biosecurity primarily depends on good behaviours from carers. Good hygiene and use of PPE, and not moving materials between different rabbits, will greatly reduce transmission risks.

We have seen a massive rise in socialisation issues in other species during lockdowns.

Rabbits have had similar problems for much longer. They are ready to socialise and learn from when they emerge from the nest. With sale not permitted until eight weeks old, clearly a large gap needs to be filled with exposure to the situations they are likely to encounter in their new “pet” home.

One of these is handling – if young rabbits aren’t handled at a very early age and in an appropriate manner, it is highly likely they will be very fearful when they are eventually handled. If this handling is by an inexperienced and not careful owner, the risk of injury to the rabbit becomes very high. Aside from not exactly encouraging further handling (handling pain is a good reason for fear aggression in rabbits), spinal damage will often result in arthritis and other issues much later in life (Figure 6).

Aside from educating breeders in socialising rabbits, we can also train owners in how to lift and hold their pets in an appropriate manner. We can also show how to provide enrichment, and set up hutches and environments to reduce stress and fear through the whole life of the pet.

And this, of course, involves having at least one companion – rabbits do not do well on their own.