8 Nov 2022

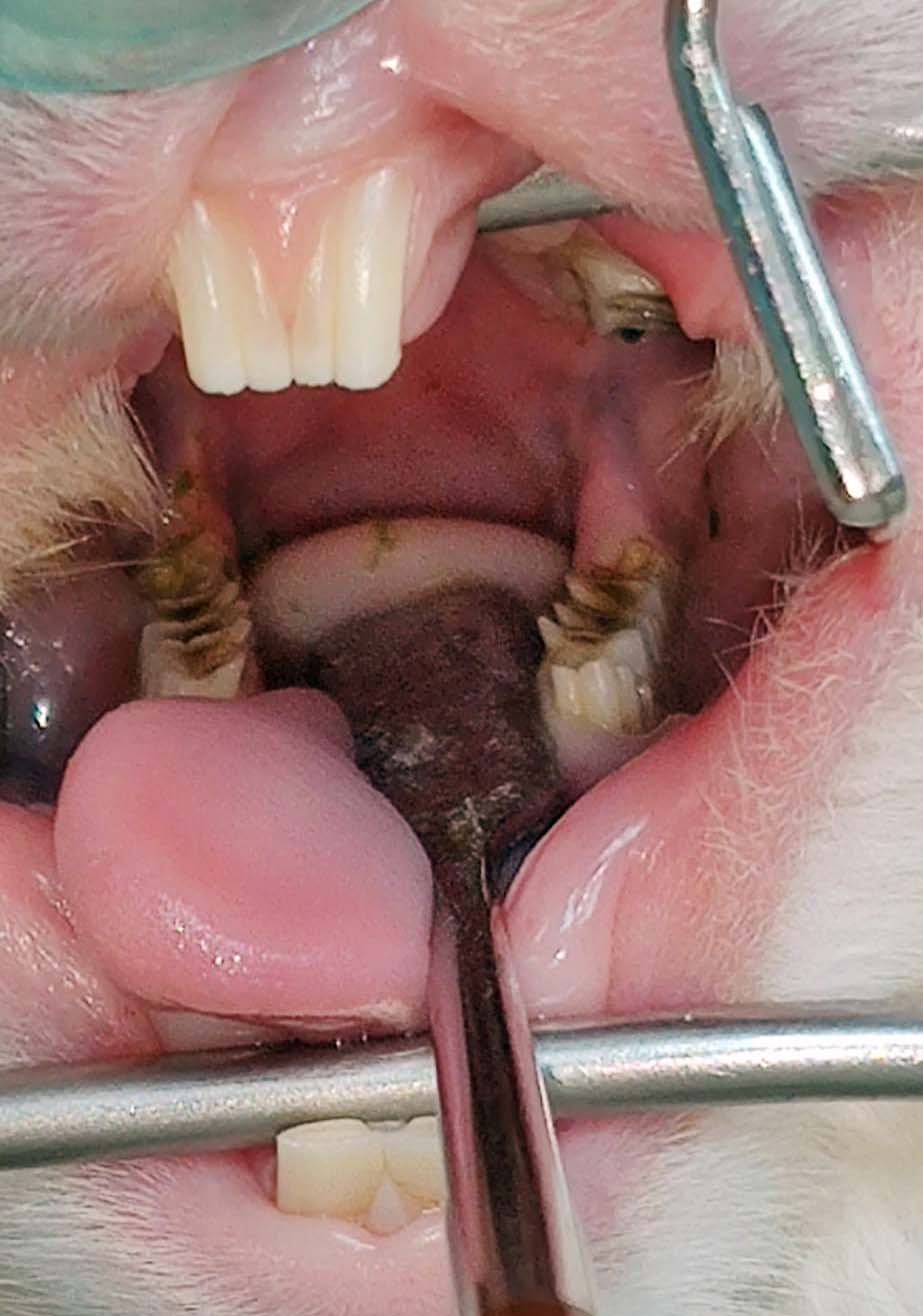

Figure 2. A typical presentation of overgrown bridging molars in a guinea pig. This impedes their ability to swallow.

Small herbivore pets – such as rabbits and guinea pigs – still remain firm favourites as small pets, especially for the younger generation.

For many years, it has been well known that these animals can suffer from dental malocclusion. As more evidence and research continues, we are understanding this condition is not just as simple as always being down to poor husbandry, although this does play a role in the development of the disease.

It is important that vets and nurses are able to understand some of the causes and preventions of this relatively common problem, as well as typical treatment and prognosis.

This article will be a quick rundown of causes, clinical signs and treatments for the most commonly seen dental conditions.

Herbivore species that are kept as pets are from various parts of the world, but the one thing they have in common is that they have evolved to eat and digest long‑stem fibres.

Part of this evolution has involved the presence of continual growing (hypsodont), open‑rooted teeth. To maintain the health of these teeth, the animal must continually cause wear by grinding plant materials containing phytoliths (silica deposits) – these deposits are directly linked to the wear of the enamel (Martin et al, 2019).

In recent times, many animal charities and associations have helped educate the public on this issue, helping to ensure these species have a constant and continual supply of hay or grass to help wear down their teeth.

However, unfortunately the development of dental disease has more causes than lack of hay/grass – and these can be broken down into the following.

Congenital malocclusion is rarely seen in guinea pigs or chinchillas, but is a common condition seen in rabbits.

Malocclusion of the incisors is seen commonly in dwarf rabbit breeds, which are often brachycephalic and lop-eared; these breeds may include the lionhead, Netherland dwarf (Figure 1) and mini lop (Crossley, 1995).

Elongation of the incisors is often seen in these animals by the time they reach the age of four months, and treatment for this condition is complete removal of all six incisors.

Congenital disease of the molars is also possible – especially in the listed breeds – often due to the crowding of the teeth in the mouth.

Unfortunately, lop-eared rabbits are also at a drastically increased risk of aural disease, including abscesses (Johnson and Burn, 2019).

Although a large majority of acquired disease is down to inappropriate diet, other causes of acquired dental malocclusion exist.

Facial trauma to these animals, involving any fractures, is likely to cause ongoing dental changes. The most common causes of trauma include fox/dog attacks, accidental stepping on – or trapping in – doors, and falls from a height.

Although education about the importance of the constant supply of hay/grass has drastically improved – and many owners provide this – the problem arises with quantities of other food sources. These species have evolved to eat low‑energy, high‑fibre food, but will seek out the higher‑energy, sweeter foods before eating hays.

Therefore, when owners provide pets with too large a portion of concentrates (pellets) and fresh vegetables, these animals will fill up on these, and either avoid hay or eat inadequate quantities to provide dental wear.

Muesli mixes have also been directly linked to dental disease in rabbits (Meredith et al, 2015); unfortunately, these foods are still available in pet stores.

Approximate quantities species should be fed can be seen in Table 1.

| Table 1. Appropriate feeding quantities for pet herbivores | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Hay/grass | Pellets | Vegetables/herbs | Dried forage/treats |

| Rabbits | Unlimited (a ball of hay the size of the animal as minimum). | A tablespoon per rabbit once a day (some may not require). | A cup of dark leafy greens/herbs/weeds (approximately 100g) per rabbit once a day. | Hay or wild food‑based dried forage and treats can make up 5% of daily food. |

| Guinea pigs | Unlimited (a ball of hay the size of the animal as minimum). | A tablespoon per guinea pig once a day (some may not require). | Half a cup of dark leafy greens/herbs/weeds (approximately 50g) per guinea pig once a day. A higher vitamin C vegetable should be offered within the portion. | Hay or wild food‑based dried forage and treats can make up 5% of daily food. |

| Chinchilla | Unlimited (a ball of hay the size of the animal as minimum). | A teaspoon per chinchilla once a day. | Minimal or no fresh foods should be given as treats only. | Dried forages and barks are often given instead of fresh vegetables. |

Unfortunately, other causes of acquired dental disease in herbivores exist that many owners cannot prevent with appropriate husbandry.

Ageing guinea pigs are prone to developing renal disease. This, in turn, causes secondary renal hyperparathyroidism that, therefore, leads to osteodystrophy.

The thinning of the bone of the jaw causes reduction of wear of the teeth and movement within the sockets, causing dental malocclusion. This thinning may also be responsible for the development of disease in rabbits (Jekl and Redrobe, 2013).

Indoor rabbits may be more prone to this issue due to reduced exposure to UV light and, therefore, vitamin D, which is essential for calcium absorption.

In older herbivores, it is likely that pain from arthritis of the temporomandibular joint and ear disease can cause changes to chewing pattern, and, therefore, malocclusion in these animals.

The clinical signs of dental disease in small herbivores varies between species – and it is important to understand this when seeing them in practice.

This species will often selectively feed when dental disease is seen. This often means they choose foods that are softer and easier to chew, such as pellets and vegetables.

Due to pain from ulceration in the mouth, they can become polydipsic.

Rabbits with incisor malocclusion will often appear with an unkempt coat due to being unable to groom effectively.

Abscesses of the jaw are commonly seen as a visible (or palpable) swelling (Harcourt‑Brown, 2007).

Due to the mechanism of overgrowth within the mouth causing molars to bridge over the tongue, guinea pigs will often lose the ability to swallow effectively or at all (Figure 2). This often leads to ptyalism.

The patient is often very hungry, and will usually pick food up and drop it out of their mouth after attempting to chew.

Guinea pig incisors will start to wear in a diagonal manner – this is indicative of overgrown molars. Dental abscesses in guinea pigs are also fairly common.

This small species is often more subtle when it comes to clinical signs. Some will paw at their mouths and hypersalivate due to pain for mucosal ulceration; others will show selective feeding, like rabbits, or drop food out of their mouths.

Many chinchillas are presented with blepharospasm and tear overflow due to the elongation of the maxillary tooth roots causing discomfort to the eye and blockage of the nasolacrimal duct (Prebble, 2011).

Conscious oral examination of these patients is the first part of making a diagnosis of dental disease; this can be achieved by using an otoscope.

Conscious examination will show obvious and severe changes in the oral cavity.

A thorough, full oral examination can only be achieved while a patient is deeply sedated or anaesthetised, and using a mouth gag and cheek dilators (Lennox, 2008; Figure 3).

It is extremely important that vets and nurses become familiar with what is normal for different species, as all have different dental anatomy. It is not unusual, for example, for inexperienced veterinarians to diagnose spurs on the lingual aspect of the mandibular cheek teeth of a rabbit – these spurs are normal anatomy, providing they are not overlong or causing soft tissue trauma (Figure 4).

Imaging should also always be performed to assess the roots of the teeth and for any signs of infection. Abscesses and changes to the roots can cause significant pain in the patient, and, in some cases, can be the cause of the presenting clinical signs – even when intraoral examination is normal.

The most superior imaging available for dental changes is CT as this avoids any superimposition of images (Capello, 2016). However, not all practices have access to this modality and not all owners will have available funds for advanced imaging.

Alternatively, radiography can be performed to assess the dental roots. A minimum of four views of the skull should be taken to fully image the dental architecture and bone density – these are lateral, dorsoventral and two oblique views. A rostral-caudal view can also be performed to assess the temporomandibular joint.

Another useful imaging method is the use of an endoscope to provide direct visualisation of the oral cavity in detail. This can be especially vital – and often essential – in the smaller species, such as chinchillas and degus, where it is likely to be harder to visualise small spurs and soft tissue trauma (Mans and Jekl, 2016).

Metabolic disease and renal disease may be difficult to diagnose. These are often made as a presumptive diagnosis based on ruling out other causes.

Treatment for dental disease in herbivores depends on the underlying cause and severity of the disease.

It is also highly important that any animal suffering from malnutrition, dehydration and weight loss due to dental disease is given a time of supportive nursing care prior to anaesthesia (Figure 5).

Any changes within the oral cavity must be corrected under anaesthesia. This involves the use of a low‑speed diamond burr to reduce height and shape the teeth back to a normal appearance.

Clipping and the use of hand rasps are contraindicated due to the risk of iatrogenic trauma, including fractures of the teeth (Jekl et al, 2008), loosening of periodontal ligaments and accidental soft tissue trauma.

Loose and fractured crowns or teeth that are infected may be removed, and patients with congenital malocclusion of the incisors should have complete removal of these teeth.

For patients suffering from root disease, long‑term analgesia is likely to be necessary for the patient to be able to eat without significant pain. For those suffering from abscesses of the roots and jaw, a more drastic approach is needed for any chance of resolution.

Abscesses within these species cannot be lanced and drained, as they would with our feline or canine patients, due to these animals producing a thick capsule and caseous puss. For resolution, the abscess must be removed in its entirety.

When this is not possible, as much infected tissue must be removed. This may involve burring of the mandible or maxilla, removal of teeth, enucleation in retrobulbar infection and extensive invasive surgery. The area must then be marsupialised open for ongoing aggressive wound flushing for several weeks to months (Meredith, 2007; Figure 6).

Culture and sensitivity of the capsule tissue should also be analysed to ensure correct antibiotics are used for many weeks to months. For many rabbit patients, this may involve injectable penicillin, which owners may be taught to administer at home.

Unsurprisingly, these patients have a more guarded to poor prognosis – and in some cases, the abscess may reform.

In severe cases of abscessation or individuals less tolerant to treatment, euthanasia may be a kinder option.

For patients suffering more metabolic disease, such as renal disease, these patients are likely to be placed on more palliative care. Long‑term analgesia is likely to be necessary, as well as regular burring of overgrown teeth.

Patients suffering from osteodystrophy may benefit from an increase of UVB exposure for vitamin D.

It is important to not overload these patients with large volumes of calcium due to the risk of developing uroliths within the urinary tract.

Prevention is not always possible in all forms of dental disease, and a genetic component to some patients developing the disease is likely to exist.

Educating the public to avoid buying brachycephalic breeds of rabbits – such as mini lops and Netherland dwarfs – may help reduce the demand for these breeds, which are more likely to develop congenital incisor malocclusion.

Good education to owners on appropriate foods and quantities in these patients is vital to avoid acquired disease from poor diet.

Unfortunately, not all dental disease is acquired from a poor diet. It is important that vets and nurses are able to recognise this, and understand the clinical signs associated with the disease in different species.

By being up to date with current research, professionals can educate owners and pick up clinical signs earlier – and this will only help to maintain better welfare in our small furry pets.