27 Aug 2021

The order Rodentia is the largest mammalian order, including more than 1,700 species (about 40% of all mammal species) distributed worldwide. These animals differ widely in size, behaviour, feeding habits, anatomy and physiology.

Based on anatomical differences of their jaw muscles, rodents are grouped into three suborders, namely:

Guinea pigs are rodents belonging to the suborder Hystrichomorpha and are among the most popular pet kept in the UK.

Inappropriate diet and husbandry are often responsible for many of the common disorders seen in pet guinea pigs (Jenkins, 2010). Dental disease (36.3%), skin disorders (33.3%) and ovarian cystic disease are among the most common conditions reported in the literature in guinea pigs (Minarikova et al, 2015).

However, a challenging mismatch seems to exist between the conditions considered as common by the veterinary profession and those found in the literature (Robinson et al, 2017).

In part two of this article, common diseases affecting the reproductive and respiratory tract will be considered. Please refer to the literature provided for more detailed information. Consideration should be given to the off-licence use of drugs mentioned.

Cysts of the ovaries have been reported to affect 66% to 75% of females aged between three months and five years (Hawkins and Bishop, 2012). They can be classified according to their origin in relation to the ovary or according to their cause (physiologic, infectious and neoplastic; Foster, 2011).

Shi et al (2002) described three different types of ovarian cysts in guinea pigs according to their anatomical origin in relation to the ovary: cysts of the rete ovarii, follicular cysts and paraovarian cysts.

In guinea pigs, ovarian cysts generally arise from the rete ovarii (serous cysts; 63.5%) or from the ovarian follicles. They are usually intraovarian and physiologic. It has been suggested that serous cysts may be a normal component of the cyclic guinea pig ovary and they appear to be non-functional (Shi et al, 2002).

Cysts can range in size between 0.5cm and 7cm, with an increase in size as the animal ages (Figure 1). No apparent correlation exists between the reproductive history of the animal and the prevalence of these cysts, whereas a significant correlation exists between age, prevalence and size of the cysts, with older animals being more likely to have one or more cysts and usually larger ones (Nielsen et al, 2003; Keller et al, 1987).

Cysts are generally filled with clear fluid – they can be single or multilocular; unilateral or bilateral. Follicular cysts are less commonly reported (22.4%) and they are thought to be functional (Shi et al, 2002). Paraovarian cysts (1/85) are thought to be non-functional (Shi et al, 2002). Ovarian neoplasia with cystic characteristics may also be found (Keller et al, 1987; Field et al, 1989; Burns et al, 2001).

Ovarian teratomas seem to be the most common ovarian neoplasm in this species (Greenacre, 2004). Other problems, mainly of uterine origin, have been frequently identified concurrently with ovarian cystic disease, ranging from hyperplasia and endometritis to neoplastic changes (Field et al, 1989; Keller et al, 1987).

Tumours of the reproductive tract are considered relatively common in this species, with many different types reported in the literature (Hawkins and Bishop, 2012; Figure 2).

Haemorrhagic vaginal discharge, abdominal distention and abdominal pain are common presenting signs (Figure 3).

Several theories have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of the rete cysts, but the topic remains controversial. Clinical signs and symptoms can vary widely depending on the type, size and distribution of the cysts.

As previously stated, cysts of the rete ovarii are thought to be non-steroidogenic, whereas follicular cysts can produce steroids, and this can affect the history, symptoms and clinical signs (Bean, 2013). Frequently, guinea pigs are asymptomatic or primary complaint may be a non-pruritic symmetrical alopecia of the lumbosacral, flank or inguinal areas, which is thought to result from the catabolic effect of the oestrogen produced by the steroidogenic follicular or neoplastic ovarian cysts (Bean, 2013; Figures 4 and 5).

Differential diagnosis in these cases should be considered. When the cysts reach a considerable size, abdominal distention (Figure 6), pain, hunched posture and reduced appetite to anorexia may also be seen.

History and physical examination are usually strongly suggestive of ovarian cystic disease. Haematology, biochemistry and urinalysis changes may not be useful for a definitive diagnosis, but are necessary for evaluation of the patient’s general clinical condition.

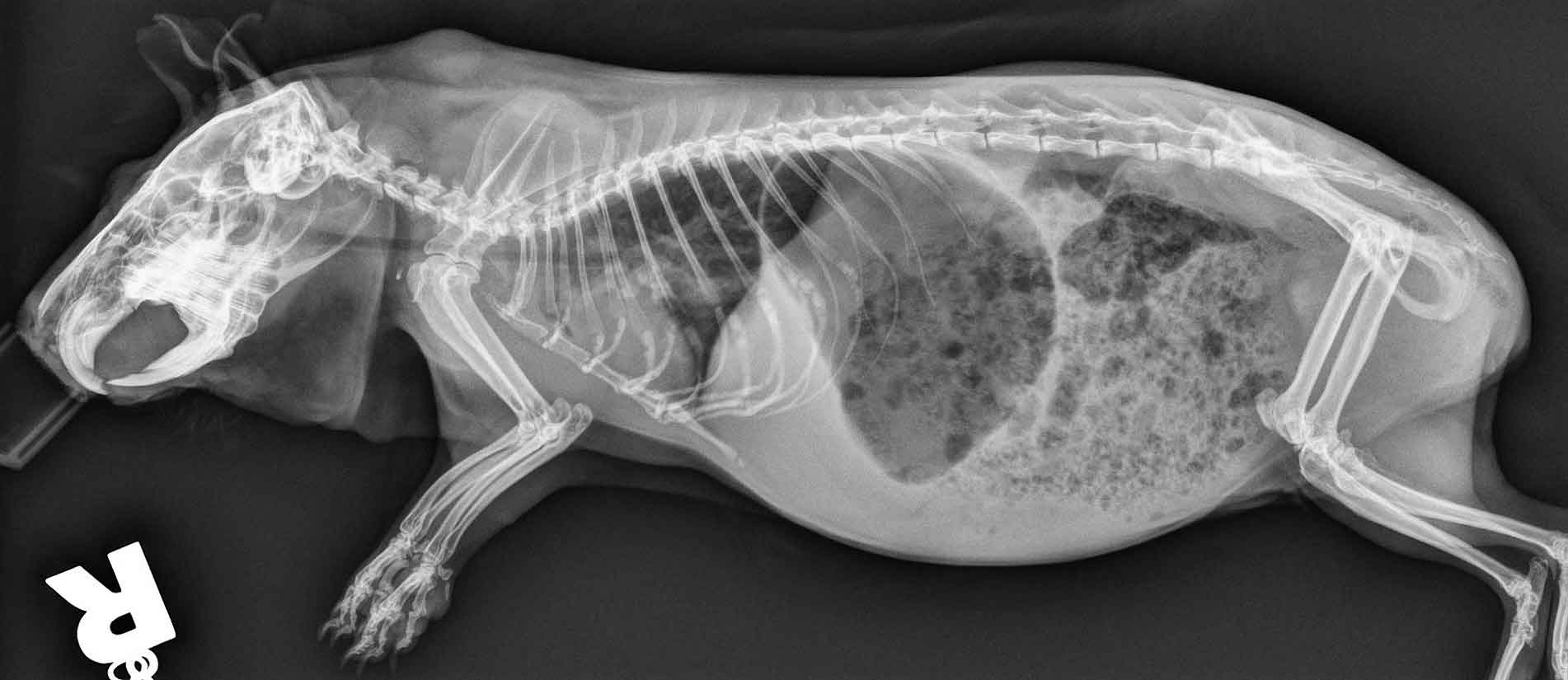

Hormonal assays are generally not reliable as cysts may or may not be steroidogenic (Burns et al, 2001). Radiography may not be very specific in identifying ovarian cysts, as their radio-opacity is similar to that of soft tissue masses or trichobezoars. Ultrasonography is the imaging modality of choice (Beregi et al, 1999).

Cysts are generally variably sized, anechoic, unilocular or multilocular, filled with a variable amount of fluid, contiguous with the ovaries and dorsal to the kidneys. Neoplastic cysts may be seen as solid masses of variable echogenicity.

Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspirate and cytology of the cyst content can be performed. However, several authors do suggest caution as this procedure may cause rupture of the cysts and/or peritonitis, haemorrhage and tumour cell seeding in case of neoplastic cysts (Bean, 2013). Sedation or anaesthesia may be required as guinea pigs are easily stressed and for safety reasons. Histopathology is required for a definitive diagnosis.

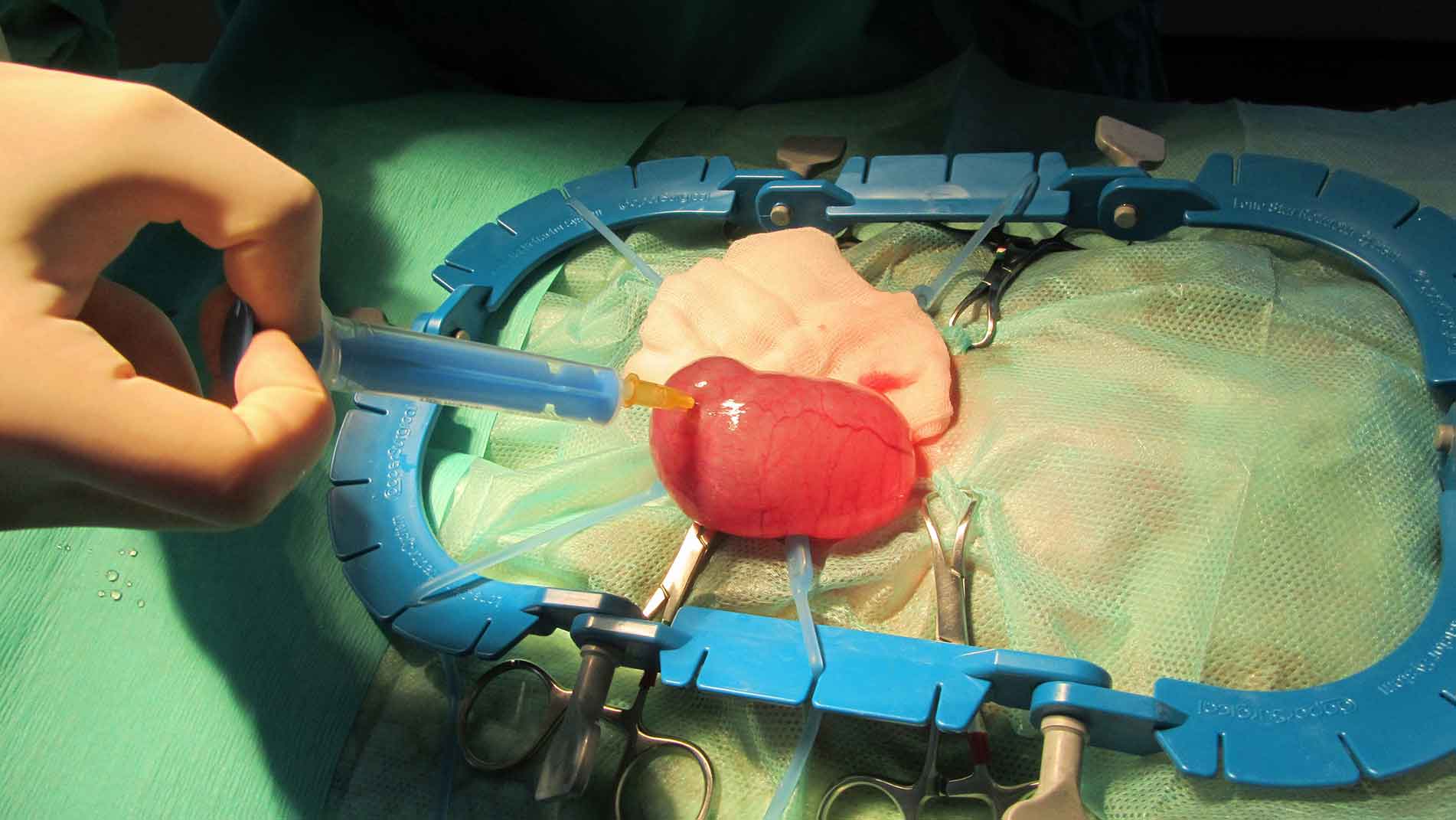

Ovariohysterectomy is considered the treatment of choice for both ovarian cysts, and ovarian and uterine tumours (Figure 7). Ovariectomy alone is not recommended because of the likely association of this condition with uterine disease.

In those cases where surgery is not an option, either due to owner’s decision/financial constraints or if the patient is not stable enough – or even in critical conditions – then medical therapy may be considered. Hormone therapy has had variable results over the years, mainly related to the type of cysts present: rete ovarii and neoplastic cysts are unlikely to respond to these therapies, whereas follicular cysts may regress and associated clinical signs resolve. The following options have been reported in the literature:

Infections of the male reproductive tract can be seen in both breeding and non-breeding boars (Hawkins and Bishop, 2012). Sexual transmission is possible, but bite wounds or haematogenous spread can also occur. Bordetella bronchiseptica and Streptococcus species are frequently isolated, but many other bacterial species have been implicated (Bishop, 2002). Culture is therefore always recommended.

Unilateral or bilateral swelling of the scrotal area (Figure 8), preputial discharge, anorexia, weight loss and hyperthermia may be seen. Unilateral testicular enlargement, with or without atrophy of the opposite gonad, may be an indication of neoplasia. Appropriate diagnosis is essential in these cases.

Targeted antibiotic treatment (preferentially based on culture and sensitivity results), supportive care and analgesia should be instituted. In some cases, castration should be considered. Where an abscess is present, an adequate surgical approach should be elected alongside medical therapy. Surgical removal and histopathology are recommended in cases of neoplasia.

Bacterial respiratory infections are frequently encountered in pet guinea pigs (Goodman 2004; 2009). Infections can be triggered by inappropriate husbandry conditions such as lack of ventilation, damp and draughty housing conditions, inadequate bedding choice leading to ammonia buildup and overcrowding. Moreover, dietary deficiencies (for example, vitamin C deficiency) and the animal’s immune status may also have an important part in the pathogenesis of these conditions.

Rabbits should not be housed with guinea pigs as they are carriers of B bronchiseptica, which is pathogenic for guinea pigs. Furthermore, both organisms are zoonotic, and can be passed between human and pet (Yarto‑Jaramillo, 2011).

A variety of microbial agents (including B bronchiseptica, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus species, Streptobacillus moniliformis and Chlamydophila caviae) have been recognised to affect the respiratory tract of pet guinea pigs. Their pathogenicity is extremely variable as they can act as primary or opportunistic pathogens.

Many respiratory infections are subclinical, and clinical signs may be absent altogether or animals may be found dead without premonitory symptoms. Symptoms are not always diagnostic, but coupled with an accurate history they can provide important clues.

Clinical signs of bacterial pneumonia in guinea pigs may be non-specific and can include weight loss, reduced appetite or anorexia, poor coat condition, lethargy and hunched posture, but more overt ones such as ocular and nasal discharge, abnormal respiratory sounds (wheezing, gurgling), lethargy, coughing and sneezing may be seen. Signs may progress to tachypnoea and/or dyspnoea.

Respiratory infections may progress to affect the lungs and tympanic bullae. Respiratory signs can also occur as secondary manifestations of cardiac or other systemic illness. Therefore, an accurate diagnosis is of utmost importance to be able to institute the most adequate treatment plan. Radiography may be helpful in these cases (Figure 9).

If the animal is dyspnoeic, emergency therapy should be started immediately and clinical examination delayed. Emergency treatment includes oxygen support, proper temperature provision (avoiding hypothermia or hyperthermia), NSAIDs, fluid therapy, assisted feeding, broad-spectrum antibiotics, bronchodilators, nebulisation and minimal patient handling.

Once the patient is stabilised, or during emergency treatment if deemed appropriate, samples for cultures obtained from tracheal or bronchoalveolar lavage should be considered (depending on the animal’s size and test feasibility) and pathogens involved treated accordingly.

Treatment requires an intimate knowledge of adverse side effects of drugs used in rodents. Most of the information related to dosing, efficacy and adverse reactions of antibiotics in rodents is anecdotal, based on clinical experience or extrapolated from other companion animals.

Some antibiotics with a Gram-positive spectrum (for example, β-lactams, macrolides, lincosamides) can lead to depletion of normal gut flora and overgrowth of opportunists such as Clostridium species and Escherichia coli – especially when these drugs are administered orally. The use of particular antimicrobials administered orally, parenterally, or via nebulisation can result in dysbiosis with subsequent fatal enterotoxaemia. It must be conveyed to the owner that treatment is not always curative and is ameliorative of symptoms at best for some diseases.

Therapy can be frustrating and unrewarding, but it should be aimed at controlling the organism, and improving clinical signs and quality of life. In many cases, the symptoms can only be alleviated for short periods. It is very important that clients are aware of the fact that infected animals may initially respond to the prescribed medical treatment, but relapses with even more severe clinical signs are possible and they can lead to a more guarded long-term prognosis.

Foreign body inhalation, choke, bloat, trauma, electrocution and neoplasia have all been reported as possible causes for non-infectious respiratory disease in guinea pigs (Hawkins and Bishop, 2012). In particular, pulmonary adenoma, often multicentric, is considered a common primary pulmonary neoplasia in this species.