6 Aug 2018

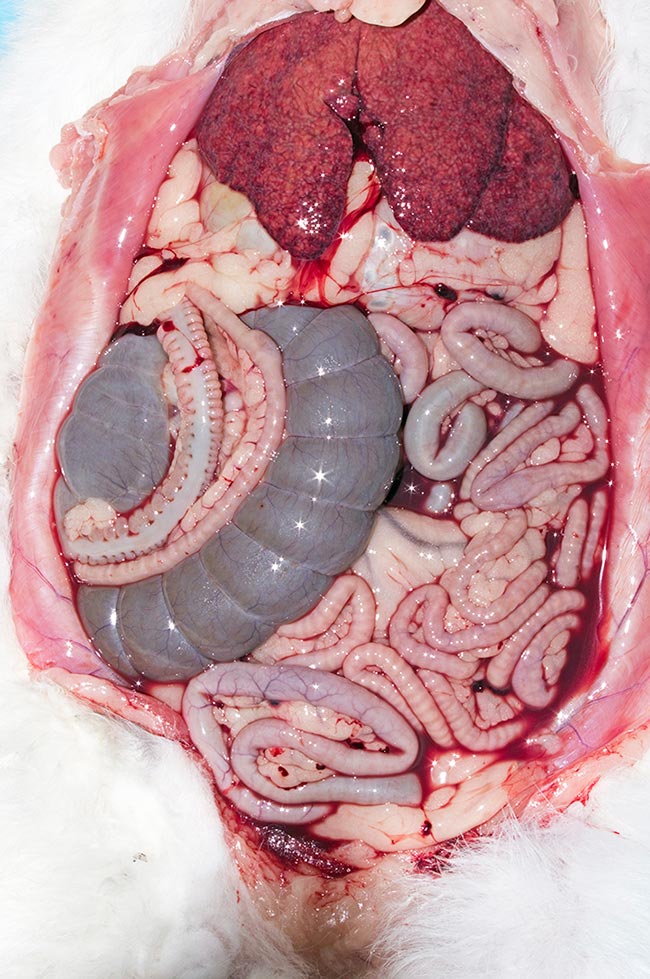

Rabbits with the rabbit viral haemorrhagic disease variant may present with a variety of symptoms, including vague signs of discomfort and gastrointestinal stasis. Image © Frances Harcourt-Brown

While classic rabbit viral haemorrhagic disease (RVHD1) has been present in the UK for decades, the variant strain (RVHD2 or RVHD variant) was first noted in 2010 in France and has subsequently been identified in the UK.

Since first noticed in the UK in 2013, RVHD2 has been problematic for many reasons. Clinically, it doesn’t look like RVHD1 (a disease even most vets have never seen, as most affected rabbits die rapidly at home); it kills rabbits of all ages; no effective vaccine existed, at least initially; and, even now, many are unaware of the vaccination options. Additionally, the rapid spread of the virus can take practices by surprise.

Nobivac Myxo-RHD (MSD Animal Health) does not offer protection against RVHD2, and neither do the previous vaccine brands available in the UK. However, RVHD1 and myxomatosis are still preventable health threats, so vaccination with this product is still vital – particularly in cases of myxomatosis.

However, work from Italy and France at the time of discovery of the variant virus suggested, with our reservoir of wild rabbits, we could expect to see RVHD2 starting to predominate over RVHD1 in the following five years or so, and this certainly seems to have become the case, with very few – if any – RVHD cases in the past 12 months showing positive on PCR testing – being positive for the original strain. In fact, no cases of RVHD1 have been detected by the APHA since 2009.

Testing in the past couple of years has been performed by private veterinary laboratories, with a number of services offering this test – based on liver samples in postmortem cases or blood or faeces in the live animal – with similar results.

As a result of the gap in the market for a product giving protection against RVHD2, the Rabbit Welfare Association and Fund arranged special import/treatment certificates for three vaccines. Since then, two licensed vaccines have been made available by the manufacturers and may be used by UK vets without having to obtain VMD paperwork – Filavac VHD K C+V (Filavie) and Eravac RVHD2 new variant (Laboratorios Hipra).

RVHD2 has some differences from RVHD1. It particularly affects rabbits of any age, as opposed to RVHD1, which is rarely, if ever, seen in rabbits younger than 8 to 10 weeks.

In practice, as younger rabbits are less likely to be vaccinated, it may be only those that die. Breeders have reported whole litters dying, while most of the adults survive. It has also been reported the variant gives rise to lower mortalities than RVHD1, although this is not necessarily borne out by some reports.

Mortality may vary from collection to collection – and possibly from breed to breed – although this may be due to husbandry, biosecurity and immunity of different individuals, rather than any direct causality. Any sex bias to morbidity and mortality does not appear to exist.

The disease onset is slower with RVHD2. RVHD1 has an incubation period of three to four days, with RVHD2 taking up to nine days to show clinical signs. Also, when signs appear, disease progression is slower.

RVHD1 may kill rabbits within 12 hours, with RVHD2 taking several days, if they die at all. Many rabbits survive RVHD2, given the much lower mortality rate, and present with a more varied clinical appearance than the classical haemorrhagic lesions.

Gastrointestinal hypomotility, anorexia, lethargy and other non-specific signs make diagnosis more difficult. Other diseases, such as bacterial respiratory tract infections, may flare up – further complicating the picture.

As suggested, diagnosis of RVHD2 is more challenging than RVHD1. The clinical signs of RVHD1 are almost pathognomonic, with the only differentials for bleeding from the orifices being anticoagulant-based rodenticide poisoning, which is very rare in rabbits; trauma (especially thoracic trauma, leading to bleeding from the nose and/or mouth); and (if confined to the female genital tract) bleeding from the uterus.

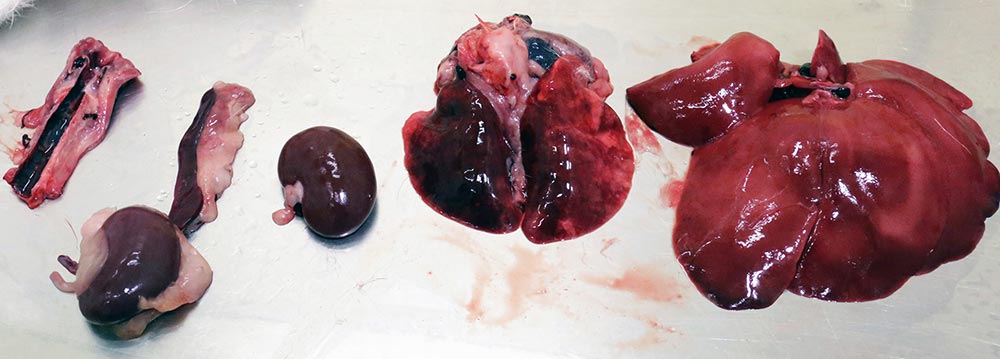

In the vast majority of cases, on gross postmortem examination, free blood is seen in the abdomen with a friable, necrotic-looking liver. The variability of RVHD2 means the aforementioned signs may be seen, or a range of others.

On postmortem examination, even at histopathology of liver lesions, the changes noted in early cases were not typical of the then expected pathology, complicating diagnosis until PCR testing was carried out.

PCR testing was initially carried out for surveillance by the APHA, and then at the Moredun Research Institute, Edinburgh. However, more recently it has been carried out by private laboratories.

A general pan RVHD test is first performed and, if positive, the virus is typed as 1, 2 or both. This test is primarily a postmortem test, with the liver being by far the best sample site to recover virus, but is also used as an antemortem test using blood and faeces.

The limitations of this are important to understand – as with any PCR test, it can only return a positive result if viral genetic material is present. Virus will not be present in blood or faeces in every case at all times, and false negatives could easily result.

Due to the surprising onset and rapid progression of RVHD1, treatment is usually ineffective. With RVHD2, however, vets have time to act; the morbidity is lower, and a range of clinical signs exist that can, at least, be symptomatically treated.

Generally, that is all that can be advised – symptomatic treatment for any secondary conditions, such as gastrointestinal stasis, and specific treatment of any recrudescent infections that flare up. It is possible therapeutics aimed at supporting a diseased liver may be helpful, such as S-adenosyl-L-methionine.

Prognosis is very difficult to determine, as it is so variable. Rabbits that have been vaccinated, but develop the disease, are likely to have significantly more chance of survival. Otherwise, it is difficult to predict, and all that can be done is to give the rabbit as much nutritional support and symptomatic treatment as appropriate.

As with any fatal viral disease where a vaccine is available, this is the cornerstone of preventive medicine. We can offer our clients vaccines against both the original strain (RVHD1), along with myxomatosis, in the form of Nobivac Myxo-RHD, and against RVHD2 only with Eravac or against RVHD1 and RVHD2 with Filavac K C+V.

It is important to remember myxomatosis is still the main viral disease of rabbits in terms of morbidity and mortality, and vaccinating with Nobivac is an essential part of rabbit preventive medicine, which must be kept up to date.

The main decision to consider is when and how to advise vaccination to cover RVHD2 as well, in conjunction with the aforementioned, and a few points should be considered.

Note RVHD1 vaccines do not cover RVHD2, and vice versa, unless both strains are present in the vaccine. Nobivac Myxo-RHD does not cover RVHD2. This may cause confusion if the expression “fully vaccinated” is used to describe a rabbit given only this, as owners may assume both strains have been covered.

Nobivac Myxo-RHD can be given from 5 weeks of age, with an onset of immunity of 3 weeks and a duration of immunity of 12 months. As with any immunological product not licensed for co-administration, a gap of at least 14 days should be left between giving Nobivac Myxo-RHD and one of the RVHD2 vaccines.

It is worth noting this doesn’t have to be 14 days – it can be much longer, allowing for, say, twice-yearly visits for pet rabbits spread out more widely over the year, allowing regular health checks to cover some of the issues rabbits may develop, such as pododermatitis, obesity, dental disease and so on.

The decision as to which of the other vaccines to use is, of course, up to the veterinary practice. Both are licensed for use in rabbits, but, as all the trial work was carried out in farmed rabbits, technically, their use in pet rabbits is off licence.

While domestic, farmed and – for that matter – wild rabbits are all the same species, this should not materially affect the efficacy and safety of the vaccines, and the cascade is being correctly followed, but vets should ensure owners give informed consent to this vaccine being used.

Eravac is an oily emulsion adjuvanted vaccine covering only RVHD2. However, unlike the older water in oil emulsions used in vaccines – which could produce potentially very severe local reactions – Eravac uses a water in oil in water emulsion. This means the oil droplets do not come into contact with the tissues, being protected by an aqueous layer.

The advantages of the oil adjuvant – a faster and more effective immune response – are therefore obtained, without the disadvantages of potential local vascular damage. Due to the presence of any oil, this vaccine still carries a safety warning to humans of the risk of self-injection, but this is much lower than with the older oil in water vaccines.

Onset of immunity is 7 days, with 100% of tested rabbits developing antibody levels by that time and the vaccine may be administered under licence from 30 days of age. This is advantageous, given outbreaks can certainly occur in rabbits younger than 10 weeks, and with RVHD2, the age-protective effect is not seen as with RVHD1, where rabbits younger than 10 weeks appear to have a high degree of immunity. Note the vaccine is effective irrespective of maternally derived antibody levels.

The vaccine has not been in use long enough to establish a full year’s immunity by challenge studies, and this has not been carried out for ethical reasons. It was fast-tracked for licensing due to the need for a vaccine and is widely used all over Europe. Although serological data supports a duration of immunity of 12 months, the product licence says 9 months based on the challenge studies to date and vets should use their clinical judgement in determining a vaccination interval.

Filavac VHD K C+V is an aluminium adjuvanted inactivated vaccine protecting against RVHD1 and RHDV2. Onset of immunity is 7 days, with challenge studies confirming protection in at least 90% of vaccinated rabbits, and proven duration of immunity is 12 months. Rabbits may be vaccinated from 10 weeks according to the licence, and in areas of high risk, from 3 weeks, repeating vaccination at 10 weeks (Le Minor et al, 2017).

One common concern with the product has been the appearance – even after thorough mixing, the product appears murky, and some users have been concerned this indicates contamination or other issues. This is, however, the vaccine’s normal appearance, and it should not be discarded.

This vaccine is also licensed for use in breeding females during pregnancy and lactation, and work has shown no reduction of efficacy in terms of antibody levels when given concurrently with Nobivac Myxo-RHD, although this would be off licence still.

Another practical consideration is the vial size, with multidose vials being useful in multi-rabbit households, and especially for breeders and rescues, with potentially dozens or even hundreds of rabbits. For multidose vials, Eravac is available in 10 × 1 dose, 10 and 40 dose vials, while Filavac is available in 50 doses. For single dose, only Filavac is available in blisters of either 5 or 10.

On the other hand, for multidose, smaller vial sizes minimise wastage and the risk of a vial being opened for too long before use (Filavac should be used within two hours of dilution; Eravac should be used immediately).

It is, therefore, important to order the appropriate vaccine vial sizes for your veterinary practice needs. Shelf life may also be an issue – especially in practices not seeing many rabbits, with Eravac being 24 months and Filavac 14 months.

Under the WSAVA’s definition, also used by the BSAVA, “core vaccines protect animals from severe, life-threatening diseases that have global distribution” and it is difficult to argue RVHD2 does not fulfil that definition, being widely distributed throughout the British Isles – including being carried to smaller islands by wind, fomites, and vectors such as insects and birds – and potentially fatal.

The author’s advice, therefore, is rabbits should be vaccinated against myxomatosis and both strains of RVHD, unless a risk benefit analysis carried out by the attending vet, in discussion with the owner, concludes otherwise. Bear in mind being a 100% indoor rabbit is no guarantee of protection, given the viruses’ persistence in the environment.

Biosecurity is one area where we can help prevent the spread of disease. In ideal experimental conditions – for example, in organ suspensions held at 4°C – RVHD can survive for more than seven months.

In less artificial conditions – for example, cool, not dry, protected from UV light, and in/on organic material, such as carcases – it has been shown to survive for at least three months. Still less optimal conditions – where the virus is cooled, but kept dry – give survival times of below one month.

Due to the virus’ resilience in the environment – especially on organic matter and in colder environmental conditions – it can spread easily over long distances; therefore, cleaning and disinfection is vital to prevent this.

Any porous materials should, ideally, be discarded. Other surfaces should be thoroughly cleaned, paying special attention to crystalline sediment in urine, which can require acidic cleaners or vinegar to break down. After that, an appropriate disinfectant should be used, at the appropriate concentration and contact time advised by the manufacturers.

Changes of clothes and gloves should be employed between handling suspected cases, and work surfaces and cages cleaned and disinfected as aforementioned. When barrier nursing suspected cases, footwear should be changed or foot dips employed.

Great care should be taken when organising health checks, “rabbit parties” or vaccination clinics, which could bring unvaccinated rabbits into contact with infectious ones.

Biosecurity advice for owners is important as an adjunct to vaccination and to protect those rabbits for whom vaccination is not possible, or in cases where it is not effective.

Owners should be warned about the potential risks of bringing in natural foods from outside. Hay, for example, has been exposed to relatively high temperatures and/or UV light, and is, therefore, safer than plants picked freshly, where infected wild rabbits may have contaminated them.

However, such foods are a hugely valuable part of a pet rabbit’s diet, and common sense steps, such as picking the highest parts of plants from areas where no rabbits are known to live (if possible), may be appropriate to reduce risks.

Owners coming into contact with other rabbits should change their clothing, including footwear – or at least use a foot dip and cover external clothing – before coming into contact with their own. They should wear and change gloves, or – preferably and – wash their hands with an appropriate antiviral product. Antibacterial liquid soap is better than alcohol-based hand gels, probably due to the more effective cleaning using the former.

Advice regarding what to do following the death of a companion is trickier to give. Firstly, the dead rabbit needs to be safely disposed of, ideally following testing to ascertain the cause of death.

Then, vaccination should be carried out in case the survivor has managed to avoid infection so far, and any new companion should be vaccinated at least one week before being introduced. But exactly how long the environment and survivors can potentially harbour infective virus is hard to tell – probably somewhere between two and eight months.

It is important to remember the conflict between preventive health care and biosecurity. Great care should be taken when organising health checks, “rabbit parties” or vaccination clinics, which could bring unvaccinated rabbits in contact with infectious ones – especially in situations where multidose vials of vaccine need to be used so quickly that adequate biosecurity is a challenge.

It’s still important to determine cause of death where possible, to avoid either over-reporting or under-reporting RVHD, and to submit samples for differential testing for RVHD1 versus RVHD2, to help determine vaccination needs for our patients in future.