3 Jun 2019

Image: Tyler Olson / Adobe Stock.

It is fair to say few vets break a sweat when presented with a healthy dog for routine castration. Flip this to a rabbit in for castration and many clinicians get a bit stressed – make this a poorly rabbit in for a dental and panic may ensue.

Despite advances in rabbit anaesthetic protocols the incidence of perianaesthetic mortality in rabbits (although improved) still remains several times that of dogs and cats (Brodbelt et al, 2008). With this in mind, rabbit anaesthesia need not be as scary as some of us think.

In this article I will cover some of the principles of anaesthetic monitoring that can help make anaesthetising rabbits safer in a clinical context.

Preanaesthetic assessment is one of the most important steps that should not be overlooked. Often very limited data exists on what the normal ranges are for rabbits, so to start by taking a conscious baseline measurement of respiratory rate, pulse rate and blood pressure in the individual patient can be a helpful tool for comparison during anaesthesia.

As a prey species, rabbits are very good at concealing signs of pain and disease, so it is not uncommon for apparently healthy rabbits to be harbouring subclinical disease such as pasteurellosis.

A full physical exam including the oral cavity, auscultation of the thorax, palpation of the abdomen and assessment of hydration are important for establishing the health status of the patient. If you suspect respiratory disease, it is advised a chest radiograph is performed to check for any lung pathology before surgery. It is also best to check the nares for good air flow, as rabbits are obligate nasal breathers and this may greatly affect your anaesthetic and oxygen delivery by mask or induction chamber.

Assigning an American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) grade (Table 1) can be a helpful prognostic indicator. It has been shown rabbits with an ASA of up to three have a much higher survival rate post-72 hours than those with an ASA of three or more (Portier and Ida, 2018).

| Table 1. American Society of Anaesthesiologists classification system used by the author to assess risk to the patient | |

|---|---|

| Physical status classification | Description |

| 1. Minimal risk | Normal healthy animals. No detectable underlying disease. |

| 2. Slight risk | Slight to mild systemic disease, but causing no obvious clinical signs or incapacity (that is animal compensating well). |

| 3. Moderate risk | Mild to moderate systemic disease, causing clinical signs (animal not compensating fully). |

| 4. High risk | Extreme systemic disease constituting a threat to life. |

| 5. Grave risk | Moribund and not expected to survive more than 24 hours. |

| Add “E” to any class if animal presents as an emergency. | |

| Source: Bednarski et al, 2011. | |

Based on this you can dramatically improve the chances of anaesthetic survival by taking time to stabilise an unwell patient prior to the procedure. Simple things such as assisted feeding, fluid therapy (IVFT), analgesia and prokinetics can all put the rabbit in a better physiological state. Don’t be afraid, in many cases, to delay the surgical procedure to stabilise your patient first. Preanaesthetic bloods taken from the jugular or cephalic vein can be useful in assessing organ function and hydration status ahead of surgery.

It is becoming standard practice to place an IV catheter for all patients undergoing surgery – rabbits should not be an exception. Placing a catheter in the marginal auricular vein means fluids and emergency drugs can be given with ease. This can be placed in most conscious rabbits with minimal restraint, having applied some local anaesthetic cream such as lidocaine/prilocaine. Although the marginal ear vein is my favourite, you can also use the cephalic and lateral saphenous vein.

Rabbits are very prone to hypothermia, so making sure they are pre-warmed in a kennel or incubator can help keep their core temperature up during the procedure.

Stress can have quite a dramatic effect on rabbits, so taking precautions – such as a quiet, predator-free environment, places to hide in the kennel and coming into the clinic with a bonded friend – can all reduce the stress an animal encounters. I have also found valerian-based calming sprays and diffusers to be very helpful in this species. Before intubating the rabbit, clear the mouth of food debris with a cotton bud or water-filled syringe.

Even if your practice does not have access to fancy monitoring equipment, fear not; you still have the most vital monitoring equipment you need – the anaesthetist’s eyes, ears and a good paediatric or oesophageal stethoscope.

The very minimum that should be observed in any animal is respiratory rate and pattern, heart rate and rhythm, pulse quality and reflexes. The normal heart rate for rabbits is 180bpm to 250bpm and the normal respiratory rate is 40 to 60 breaths per minute. Obviously, this can be raised if the animal is stressed or slowed due to anaesthetic protocol. Similarly, this will change with depth of anaesthesia and response to painful stimuli, as do other mammals.

The depth of anaesthesia can be tricky in rabbits as they are a prey species, therefore they may exhibit fear paralysis, so reflexes may be falsely reduced or absent.

Depth can be determined by eye position as with cats and dogs, but do consider the limitations when ketamine is used in the anaesthetic protocol as this often leads to a fixed eye position. Surgical/deep anaesthesia is shown by reduced muscle tone (including anal tone). Palpebral and corneal reflexes should be reduced or absent (the palpebral reflex is often not reliable in rabbits).

One of the most useful responses, clinically, is lack of response to painful stimuli – for example, a toe pinch or pressure on the pinna. If any limb movement, sudden tachycardia, hypertension or tachypnoea is observed once surgery has begun, the rabbit is not sufficiently anaesthetised and may need additional analgesia.

Capnography was something that scared me when I first started to use it, but once you get your head around the different traces and what they mean, it can provide you with a lot of reassurance and vital information about how well your patient is ventilating. It does require the patient to be intubated and can be used alongside ventilators. Hypoventilation and hypercapnia can be problematic with any animal under anaesthesia.

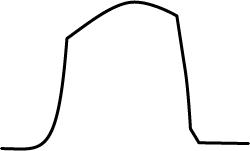

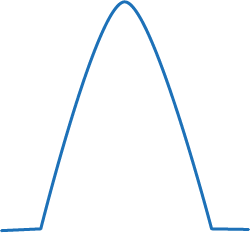

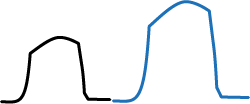

A capnometer will measure the maximum volume of CO2 at the end of expiration (end tidal CO2; ETCO2) and this correlates with the arterial concentration of CO2. The machine produces a capnograph and it is the shape of this that gives you insight as to how your patient is doing under anaesthetic (Table 2). With rabbits, a mainstream system is better than a side stream as less dead space is involved.

| Table 2. General capnography shapes you may encounter and what they might indicate | |

|---|---|

| Capnograph shape | Meaning |

|

Normal shape trace |

| No shape to the trace at all indicates you are not in the airway. This indicates oesophageal intubation, extubation or blockage/disconnection. It may also mean your patient is apnoeic or in cardiac arrest. | |

|

This trace shows the sampling tube may have a leak or the tube itself has become dislodged. |

|

Going from normal to larger trace would indicate an increased metabolic rate. This is seen in animals that are shivering, have hyperthermia, are seizing and in hypoventilation. It could also indicate bronchial intubation. |

| This table is a very generalised and simplistic summary, but can be useful when first getting to grips with capnography. The trace of the graph can tell you how successful your intubation technique has been and reassures you your patient is ventilating appropriately. The author would urge use of this on as many routine patients as possible, so you become familiar with the expected traces you get from capnography. | |

A gradual rise in ETCO2 may indicate your patient is too deep; a gradual decrease and your patient is too light or painful. A sudden drop or absence of a trace may indicate extubation, apnoea or cardiac arrest. As this device measures in real time you can pick up on abnormalities quickly, intervene and see the response to the intervention without wasting precious seconds.

Normal blood pressure readings in rabbits are:

Blood pressure gives you information about tissue perfusion (especially the kidneys), the need for IVFT, depth of anaesthesia and cardiovascular status. Two methods exist:

This type of monitoring would be worth considering in particularly unstable patients or for extended procedures. This is the gold standard for measuring blood pressure and also allows for blood to be taken intraopertively for blood gas analysis. This may be overkill for your routine patients and so indirect measurement may be better in that case.

Pulse oximetry is a nice non-invasive way of measuring oxygen saturation in your rabbit, but it can be less reliable then capnography. However, it is a piece of the bigger clinical picture. As with other animal species, you don’t want the oxygen saturation to drop to less than 95%.

The probe can be attached to the tongue, ear, paw or tail base. Do bear in mind the fragility of veins in rabbits as the compression of the probe may cause the vessel to be occluded and give a poor reading. Frequent repositioning may aid with this problem. Similarly, poor readings may be due to vasoconstriction of peripheral vessels with α-2 agonists and animals with lots of hair or pigmented skin. I would not use this device for measuring heart rate as it is often not capable of reading the very fast heart rates encountered in small mammals.

Although not the most technical aspect of monitoring anaesthesia, I can assure you that you will have better recovery in your rabbit patients if you pay good attention to thermoregulation. Rabbits have a large body surface to mass ratio and so lose heat very quickly – therefore, are prone to hypothermia. Core temperature should ideally be measured before, constantly during, and in recovery. A basic thermometer or rectal probe thermometer can be used. Using a bair hugger, blanket, heat mat, bubble wrap and other warming aids are all good ways to keep the patient warm, but continual monitoring should ensure the rabbit does not become too hot and be weary for iatrogenic skin burns.

Although trickier than in cats and dogs, intubation is a skill worth mastering. Not only do you have full control of the airway should the worst happen, but it is much better at providing oxygen, can be connected to a ventilator and also allows the use of capnography.

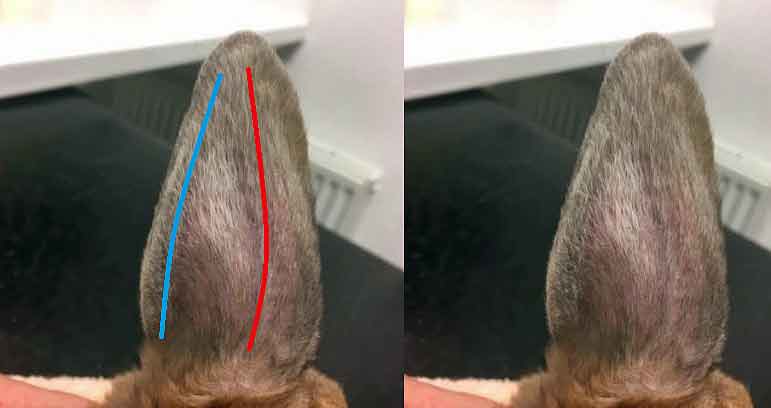

I have also used supraglottic airway devices (Figure 2):

These can be a useful alternative to intubation, but it’s important you get the correct size for the patient and follow the specific directions for placement.

Again, I would check correct placement with capnography. Take care, as if the tube dislodges, it can obstruct the airway.

It is important to monitor the rabbit in recovery as well as anaesthesia as a lot of animals will often crash in recovery rather than under anaesthetic. Respiratory rate, heart rate/rhythm, pulse quality and return to consciousness should all be monitored closely at this time. Keep checking a patent airway is maintained as this species are prone to laryngospasm following extubation – especially if iatrogenic trauma has been caused by initial intubation.

Non-invasive monitoring, such as pulse oximetry, auscultation and blood pressure measurement, should continue until the animal is able to hold its head up and sit in sternal recumbency. Once awake and aware, the patient can be monitored from a distance with minimal interference to reduce stress.

An incubator is ideal to maintain body temperature during recovery and provide a stress-free flow of oxygen, if needed. Once awake enough, syringe-feed a suitable herbivore liquid diet and encourage feeding as soon as possible.

I have summarised some of the basic principles in monitoring your rabbit patients during anaesthesia as, with any patient, no one piece of equipment will lead to successful anaesthesia. Instead, use these to put together the overall clinical picture.

Do not lose your head over the fact your patient is a rabbit; use the basic principles of anaesthesia you would with any patient species. I urge you to use these monitoring techniques in the elective patients to get experience for what normal feels like. This will help vastly when you have a riskier anaesthetic candidate where you may have to respond to more subtle changes quickly.

Thank you to the Rabbit Welfare Association and Fund for allowing the use of rabbit photographs for this article.