10 Jul 2023

Tendons are elastic structures that connect muscle to bone. They are composed of longitudinal fibre bundles that run parallel to one another. Unlike muscles, tendons have a poor blood supply that impacts on tissue healing.

Tendons can be found throughout the equine body. Those of the upper limbs and body tend to be short, whereas those of the distal limb are comparatively quite long. Tendons of the distal limbs – the digital flexor and extensor tendons – have very little soft tissue protection, leaving them vulnerable to injury.

They are also the most important because of their impact on the horse’s athletic career. The following article refers to flexor tendon injury, but it can be extrapolated for other tendon injuries.

Tendon injury types include:

Tearing of tendon fibres commonly occurs during exercise, such as with horses in fast work, exercising on unlevel ground, very deep surfaces or strenuous exercise in unfit horses. The degree of fibre damage can range from mild (minimal damage) to severe (complete rupture).

Usually, fibres are damaged within a localised area/zone (see diagnostics).

Tears can form holes within the tendon, or one may see disruption to the outer limits of the tendon. Both types can be of varying length. Over-reach or sharp injuries can cause mild injury, such as bruising and skin abrasions, to complete tendon ruptures (Figure 1).

Depending on where the injury has occurred, one must consider involvement of the digital flexor tendon sheath (DFTS), as a wound that communicates with this structure can lead to a life-threatening infection if not dealt with proactively.

Inflammation or tendinitis will commonly be picked up as heat and “bowing” of the affected limb.

Acute tears may result in significant lameness initially and appear significantly improved within 24 hours.

Horses with severe tendon fibre damage or rupture and/or involvement of the digital flexor tendon sheath are markedly lame, and it will be sore to palpate the area:

Clinical examination should include a lameness evaluation to localise the area of concern. During palpation of the limb, careful attention should be paid to presence of any heat, painful response to light/hard pressure, subtle enlargements and consistency of the tissue (soft if acute, firm if chronic). Always check for evidence of trauma, such as a small wound.

Ultrasound is required to determine the exact location and extent of the injury. An initial scan the day of acute injuries is advisable if significant tendon damage is suspected. The optimal time for a baseline scan in most cases is approximately one week after the initial injury. This allows for a more precise interpretation of the extent of the injury. Scanning earlier than this can lead to an “underestimation” of lesion severity.

Comparing the affected limb with the contralateral leg can help for comparison, but also because palmar lesions can be bilateral. A 7.5MHz linear transducer is best, but a rectal probe will work well for the flexor and extensor tendons. Have the horse standing square, where possible, and images should be taken in the transverse and longitudinal plane. Two methods are used for identifying the location of lesions in the distal limb:

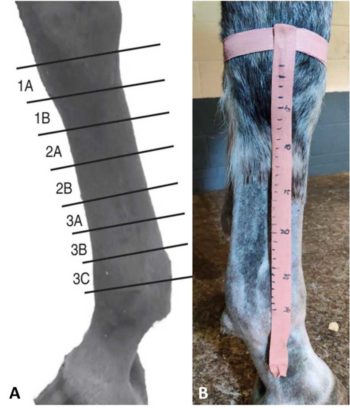

Metacarpal region is divided into seven equally sized zones with their own characteristic anatomy (Figure 3a)1.

Position of the transducer relative to the accessory carpal bone in centimetres (Figure 3b).

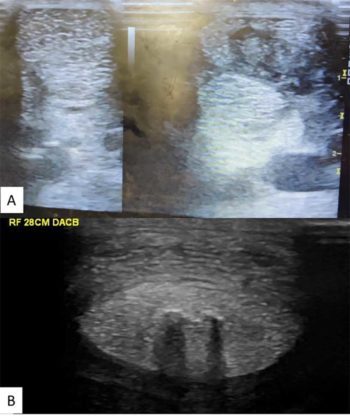

Acute tendon pathology is characterised by changes in the shape, margins, enlargement, focal or generalised hypoechogenicity, and reduced fibre pattern (Figure 4). In cases of chronic tendinopathy with fibrosis, one may see variable enlargement, echogenicity and irregular fibre pattern. In some cases, ultrasound may not provide a definitive diagnosis. An example would be longitudinal tears in the DDFT, where further imaging is required, such as contrast radiography or MRI.

One study showed that in flat-racing Thoroughbreds, in cases of SDF tendonitis, the cross-sectional area was the most significant factor determining a successful return to racing. If the lesion was less than 50% of the total cross-sectional area, horses had 29% to 35% likelihood of racing; if the lesion was greater than or equal to 50%, this dropped to 11% to 16%.

In cases without a core lesion, longitudinal fibre pattern best predicted a successful return to racing; if the affected longitudinal fibre pattern was lower than 75% of the total, horses had 49% to 99% probability of a return to racing, but if it was equal to or greater than 75%, this dropped to 14%2.

Overreach/wounds are assessed by ultrasound on the day of injury. Other diagnostics, such as pressure testing and/or synoviocentesis of the digital flexor tendon sheath, may also be indicated, depending on where the wound is located (Figure 1).

Despite all the progress made in treatment options for tendon injuries, still nothing can guarantee a permanent return to soundness.

As previously mentioned, tendons have a poor blood supply in comparison to muscles and other tissues within the body, which is one of the issues regarding post-injury healing.

The other major issue is damaged tendon fibres do not repair in a mirror image of pre-tendon fibres; instead, scar tissue forms, leading to an area of tendon that is significantly less elastic to the original tissue, resulting in a weaker tendon that is more prone to re-injure. For tendon injuries, excluding those with associated wounds, treatment for the first 10 to 14 days should include:

These four steps are all aimed at reducing inflammation and pain, while preventing further injury to the tendon. Once the initial inflammation is under control, and the extent of the lesion has been determined, a controlled exercise programme can be started and further treatment options considered.

For short-term management of DDFT lesions, raising the heels can help reduce tension on the tendon. This should be avoided in the long term, as it will lead to heel collapse.

For SDFT injury, extended length and/or increased width at the heels or /egg-bar shoe should be considered (Figure 5). The toe/wider toe width should be raised.

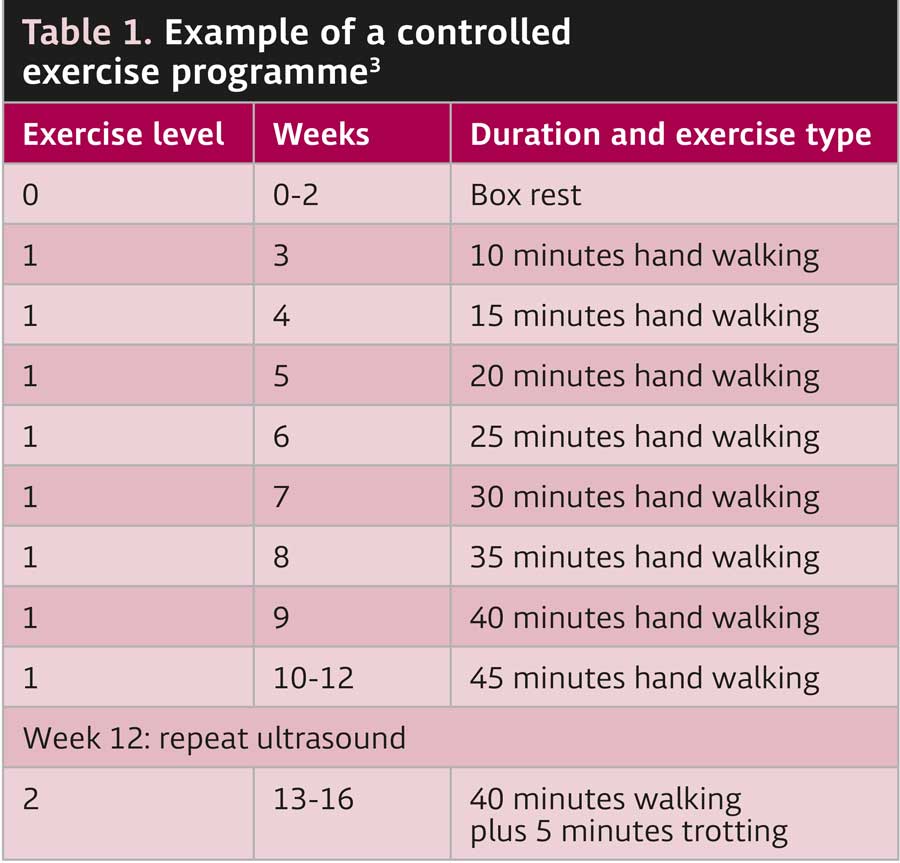

Controlled exercise is an integral part of the management of tendon lesions. Most flexor tendon injuries can take 6 to 12 months of rehabilitation before the horse goes back into full athletic function. Exercise programmes are tailored to the animal and lesion severity.

The aim of a controlled exercise programme is to optimise scar tissue function, maintain the gliding function of the tendon and promote optimal collagen remodelling, without causing further injury.

Table 1 provides an example of a controlled exercise programme3. The programme should be adapted based on serial ultrasound exams to ensure the tendon can withstand the exercise. This can be done at set time points, such as every four to six weeks, or before and after increasing exercise work; for example, from walk to trot, trot to canter, and canter to gallop.

An increase in the cross-sectional area of the tendon by greater than 10% between exams is highly suggestive of re-injury. The exercise level should be reduced if this is observed. In some cases, the horse will not be able to manage the increasing exercise or return to its previous level of athleticism.

Underwater treadmills, in conjunction with a controlled exercise programme, should be considered, as they allow for musculoskeletal conditioning with minimal concussive forces on the limbs.

Intra-lesional medication should be done no earlier than three days after initial injury, via a fully aseptic ultrasound-guided technique (Figure 6).

Cell-based therapies, such as mesenchymal stem cells, regenerate diseased tendons and have shown significant potential. RenuTend has recently been released and is reported by the manufacturer to improve fibre alignment and reduce scar tissue formation. A controlled study on its efficacy is lacking.

Cell-based therapies, while likely to become more mainstream in the future, are still cost prohibitive to many clients.

Regarding regenerative techniques, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and autologous conditioned serum have shown promising results. When injected into the lesion, the growth factors encourage new blood vessels to grow, resulting in more normal fibres developing.

Polysulphated glycosaminoglycans and hyaluronic acid (HA) have conflicting evidence regarding re-injury rates. HA is probably best used intrathecally to try to reduce adhesion formation within the tendon sheath.

Tendon splitting is used for acute tendinopathy to “decompress” the lesion by removing the seroma/haematoma and it may also help prevent lesion propagation. It should be avoided in chronic cases, as it leads to extensive granulation tissue, increased tendon trauma and persistent lameness.

Tenoscopy/bursoscopy is advantageous as it provides both an assessment and management of the lesion.

Tenoscopy is performed in cases where concurrent infection of the DFTS is present; during this time, any damaged fibres can be resected. In some cases, the surgeon may suture the severed tendon edges.

Counter-irritation is applied chemically (topical iodine compounds) or thermally (firing or freezing) to the skin over the injury site.

Tendon injuries are commonly seen in horses, with the digital flexor tendons the most commonly affected. These injuries pose a significant threat to the animal’s athletic function, with severe injuries being life threatening. In the acute stage of injury, cold therapy, anti-inflammatories, compression, support and rest are vital.

Ultrasound is crucial to the diagnosis and guides the practitioner on severity and treatment options. Intralesional injections of stem cells or PRP have shown improvement in the healing of tendon fibres and are becoming more widely used. Stem cell therapy will likely become more routinely used in the future.

Studies evaluating re-injury rates using these techniques are lacking, but would be invaluable in helping vets determine the best treatment options for their patients.