10 Sept 2018

Being able to recognise the early signs may trigger the Addison’s disease alarm bells. Image © georgerod / Adobe Stock

Equine viral arteritis (EVA) is a respiratory and reproductive disease caused by equine arteritis virus (EAV).

The virus was identified subsequent to a respiratory disease and abortion outbreak on a stud farm in Ohio, US, in 1953 (Doll et al, 1957). It has since manifested worldwide with varying severity – from subclinical to lethal.

Generally, horses have a flu-like syndrome (Balasuriya et al, 2016). EAV infection clinical signs vary depending on various factors, including the challenge dose, infection route and virus strain (Balasuriya et al, 2016).

Some signs often seen with clinical EAV infection are dependent oedema of the scrotum, mammary gland, ventral trunk and limbs; conjunctivitis with ocular discharge; and periorbital and/or supraorbital oedema, which gives it the colloquial name pink eye.

Abortions may occur between 2 months and younger than 10 months of gestation, affecting between 10% and 70% of mares without warning (Doll et al, 1957; Cole et al, 1986; Timoney and McCollum, 1993; Balasuriya et al, 2016).

A novel feature of EAV is it can persist in between 30% and 60% of infected stallions (Timoney et al, 1986; 1987; Neu et al, 1988), with the virus persisting in the accessory sex glands. The carrier state in stallions – otherwise known as “shedders” – is testosterone-dependent, so no carrier status exists in mares, geldings and prepubertal colts (Timoney and McCollum, 1993). The modes of transmission are well illustrated by Newton (2007) and Balasuriya et al (2016).

The UK does not knowingly have EVA present in its horse population; however, it does not declare itself EVA free. EVA is, however, legislated for and a notifiable disease in the UK, controlled under The Equine Viral Arteritis Order 1995. Guidance on EVA from Defra and the APHA is provided on the GOV.UK website (GOV.UK, 2014).

So, why do we screen horses in the UK if we don’t have the disease? We are vulnerable to it and our borders are not guaranteed to prevent its introduction.

An acutely infected mare could introduce the virus if it is moved from outside the UK into the UK and infects other horses subsequent to horizontal transmission via the respiratory or reproductive routes, with the latter being via contact with the products of abortion.

A colt, stallion or gelding could also introduce the virus if it was acutely infected and spread the virus via the respiratory route. The stallion, as aforementioned, could also be a carrier; it is persistently subclinically infected, with the ability to spread the infection via the reproductive route – either via natural cover or AI.

Therefore, importation of horses into the UK risks the introduction of EVA, so it is ironic no statutory requirements exist for pre-entry or post-entry testing of horses entering the UK from EU member states.

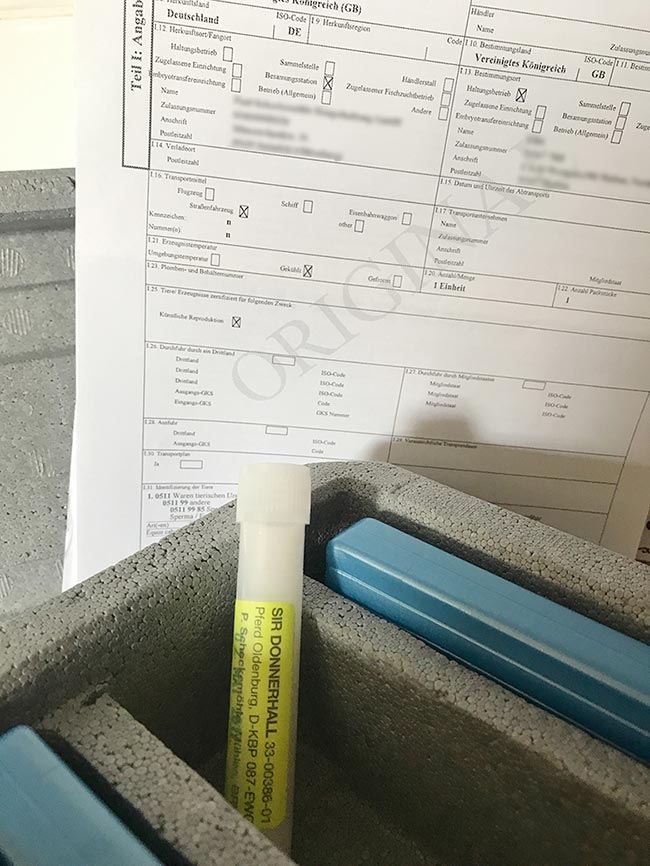

The ability of the virus to remain infectious in chilled and cryopreserved semen means importation of semen into the UK is another source of introduction. However, unlike the importation of horses, mechanisms are in place to prevent the introduction of EVA via semen imports – all chilled and frozen semen imports arriving from the EU should be accompanied by an original certified intra-community trade certificate (Figure 1).

Semen without appropriate certification represents a significant EVA risk. Chilled semen reaching the UK border without certification will likely pass border control agencies and be delivered to its destination into the hands of a vet to inseminate a mare. It is that vet’s responsibility to notice the lack of certification, acknowledge this is an illegal import, not inseminate the semen and report appropriately.

The long-term implications of the disease for mares and geldings are minimal, as individuals will likely make an uneventful recovery. For stallions, however, it is a different matter. No known effective treatment exists for the carrier state, other than castration (Little et al, 1991).

Promising investigations exist into the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) vaccination to eradicate the virus from carriers (Burger et al, 2006); however, use of GnRH vaccines to suppress testosterone levels has obvious negative effects on the breeding potential of vaccinates.

Use of GnRH antagonists has been proposed as a potential treatment for the carrier state, with the effects on testosterone having a greater degree of reversibility than GnRH vaccination; however, EVA clearance has not yet been proven (Fortier et al, 2002; Davolli et al, 2016).

Despite the potential for treatment, The Equine Viral Arteritis Order 1995 does not accommodate this – and a stallion found to be positive for EAV in its semen, and castrated to ensure the virus has been eliminated, could be declared EAV free.

It is possible, if recently imported, the stallion would be exported to its country of origin. No compensation would be provided in the event of this happening.

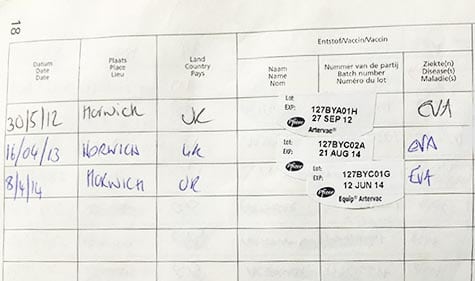

Many UK stallions will be vaccinated in an attempt to prevent them from being infected and carriers. The Horserace Betting Levy Board (HBLB) Code of Practice for Equine Viral Arteritis recommends breeding stallions are vaccinated against the disease using Equip Artervac. Following vaccination, stallions may become serologically positive.

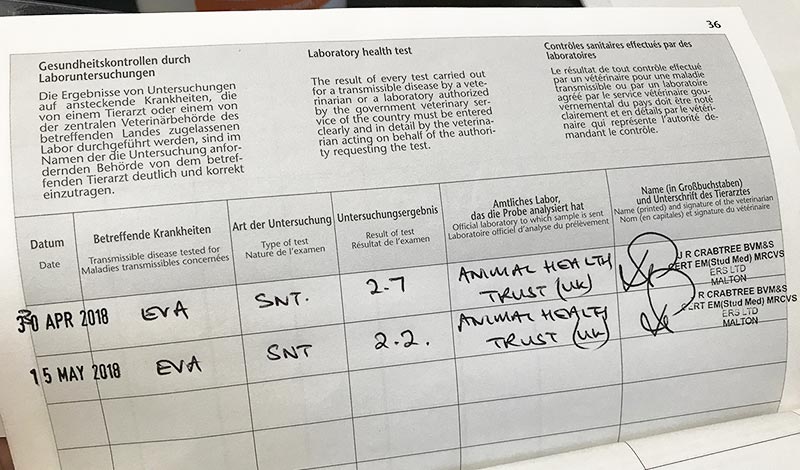

As no ability exists to differentiate antibodies derived from vaccination from those produced after natural infection, it is essential to demonstrate a horse was serologically negative prior to vaccination and the post-vaccination seropositive status is consistent with the history of vaccination.

The negative pre-vaccination result should be certified in the horse’s passport under the “health tests” section and acts as a permanent record.

Essentially, we are testing for EVA as part of an ongoing serosurveillance of the disease – to prevent outbreaks and the potential for infection of our UK resident stallions.

Screening is generally performed prior to the onset of breeding activities, as described in the voluntary recommendations made by the HBLB Code of Practice. Many UK studs and AI centres require pre-entry serological screening for EVA, among other infectious diseases (Figure 2). More often, this is done in veterinary laboratories using a kit-based ELISA test and is reported as being either negative, inconclusive or positive.

An inconclusive or positive result should be referred, usually to the AHT for a serum or virus neutralisation (SN or VN) test. An initial result should be reported quickly; however, confirmation via a VN test will take a few days.

What should clinicians do if a mare or gelding tests positive? It is important to ask whether the individual has clinical signs of EVA. Assuming it does not, it is likely the positive antibody titre is a result of previous exposure to EVA.

The mare should be isolated as a precaution and re-bled after 14 days, with the sample sent to the same laboratory that confirmed the first positive VN result for paired serology. Stable or declining VN antibody titres indicate the mare or gelding is not considered likely to be infectious (Figure 3). In the author’s experience, all positive mares have originated from outside the UK.

Increasing antibody levels or clinical signs of EVA infection – especially in a mare that has been naturally mated or artificially inseminated within 14 days – necessitates reporting under The Equine Viral Arteritis Order 1995 to the APHA.

If a stallion tests positive by VN test, this represents a different scenario. It is necessary to determine whether the stallion has any history of vaccination against EVA. If the result is not recorded in the stallion’s passport, be sure to check clinical records, or any previous vet records, as the test may have been performed, but not entered into the passport.

In the absence of any evidence of vaccination under The Equine Viral Arteritis Order 1995, this should be reported to the APHA’s divisional veterinary officer. This can be done by contacting the APHA’s animal health and welfare services department.

As all clinicians know, it is common for owners to inadvertently, or otherwise, allow vaccinations to lapse – some may have started then discontinued as they felt it was no longer necessary, or too expensive, to continue, while others may have lapsed due to vaccine supply issues. If a stallion has been previously vaccinated, but these have lapsed, regardless of the cause – in the absence of clinical suspicion of disease – it may be more appropriate to screen for the disease by semen testing, rather than blood testing, in the first instance.

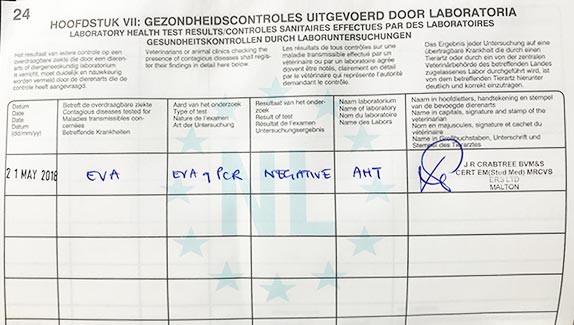

Analysis of a raw semen sample for presence of EAV can be performed in the UK by the AHT or the APHA’s Weybridge laboratory. Detection is performed by quantitative PCR assay and/or virus isolation in cell culture (Figures 4 and 5).

It should be stressed if the attending clinician knows, or has reasonable grounds for supposing, a stallion is infected with EAV, it is his or her responsibility – under The Equine Viral Arteritis Order 1995 – to report such a stallion to the APHA.