21 Jan 2021

Image: Mari_art / Adobe Stock

Laminitis is now considered to be a clinical syndrome associated with systemic disease (sepsis or systemic inflammatory response syndrome, or endocrine disease) or altered weightbearing, rather than being a discrete disease entity. Three forms of laminitis exist – sepsis-associated, endocrinopathic and supporting limb.

A wide range of clinical signs are displayed by laminitic cases and no individual – or combination of – clinical signs are present in every case. The signs that have been shown to be the most useful when trying to distinguish laminitis from other lameness causes are the presence of “reluctance to walk”, “short, stilted gait at walk”, “difficulty turning”, “shifting weight” and an “increased digital pulse”.

Owners recognise laminitis in approximately half of cases that are subsequently diagnosed as laminitis by a vet. Undefined lameness, foot abscesses, colic and stiffness are common reasons for owner-requested veterinary visits in owner-unrecognised cases. Therefore, further targeted owner education is required to raise awareness of the clinical signs that have been shown to be most commonly associated with laminitis, rather than those commonly perceived to be present. Providing owners with a list of potential clinical signs to be aware of, including questions relating to management and clinical history of their animals, could encourage more rapid and proactive decision-making.

Treatment of laminitis consists of providing foot support and adequate analgesia, as well as treating any underlying condition.

Laminitis is now considered to be a clinical syndrome associated with systemic disease (sepsis or systemic inflammatory response syndrome [SIRS], or endocrine disease) or altered weightbearing, rather than being a discrete disease entity.

Three forms of laminitis exist:

The symptoms of laminitis are the same regardless of type and include any combination of:

The lameness can vary in severity – from that which is only perceptible at the trot, through to spending prolonged periods recumbent.

It should be remembered some episodes of laminitis are subclinical and while no overt lameness (or any other clinical sign) may exist, it subsequently becomes apparent as divergent hoof growth rings.

A recent study sought to establish the extent owners were able to recognise laminitis, and the basis on which they did so2.

Of the 93 cases of veterinary-diagnosed active laminitis included in the study, 51 (54.8%) had been suspected as having laminitis by their owners. All 51 of these owner‑suspected cases of laminitis were confirmed by a veterinary surgeon – no “false positive” cases of owner‑suspected laminitis were reported. Nearly 80% of the owners who suspected laminitis, which was also subsequently diagnosed by a veterinary surgeon, had previous direct experience with the disease.

The 42 (45.2%) owners who did not suspect laminitis in their animals either did not know what the problem was, or suspected another lameness condition (foot abscesses, bruised sole or navicular disease) or another condition (colic, musculoskeletal stiffness, sunburned heels and swollen sheath).

When the clinical signs associated with laminitis reported by the owner and attending veterinarian for the same horse were compared, consistency existed for the reported presence of most clinical signs, underlying conditions and risk factors associated with laminitis. However, significant differences existed for four clinical signs – difficulty turning and weight shifting were more frequently reported by vets, while increased hoof temperature and recumbency were reported more frequently by owners2.

Additionally, owners were less likely than vets to report EMS as an underlying condition and less likely to recognise laminitis in non-pony breeds.

A second study aimed to compare the prevalence of selected clinical signs in laminitis and non-laminitis lameness cases to evaluate the capabilities of clinical signs to differentially diagnose laminitis from other causes of lameness3.

A wide range of clinical signs were displayed by the laminitic cases and no individual – or combinations of – clinical signs were present in every case. The clinical signs that were considered to be the most useful were three features of lameness investigation (“reluctance to walk”, “short, stilted gait at walk” and “difficulty turning”), one feature of stance (“shifting weight”) and an “increased digital pulse”. All these signs had a difference in prevalence of greater than 50% between active laminitis cases (signs more prevalent) and non-laminitic lame horses (signs less prevalent).

Two clinical signs – “coronary band depression” and “prolapsed sole” – that are considered pathognomonic for laminitis were only found in 13.6% and 3.7% of cases, respectively. Additionally, “front feet in front of the body” – taken to represent the classic “laminitis stance” – was found in less than half of the diagnosed active laminitis cases, and did not prove to be a useful discriminator.

Therefore, despite much anecdotal publicity of this visibly apparent clinical sign, veterinarians and owners should be careful to avoid relying on its presence for making a diagnosis of laminitis.

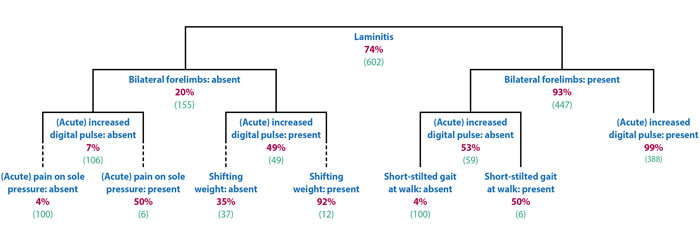

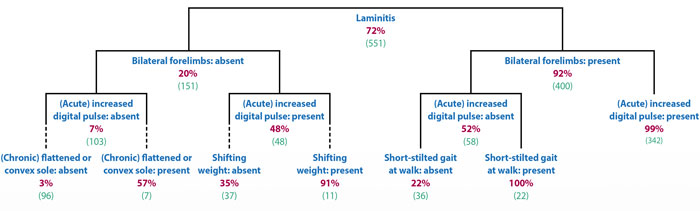

Two overall combined trees were generated to reflect the two clinical scenarios of active laminitis – one consisting of clinical signs considered to occur in the acute phase of the disease (Figure 1), and one that also contained data reflective of lamellar damage and displacement of the pedal bone (Figure 2).

In both scenarios, the presence of a bilateral lameness was the most useful discriminator, followed by the presence of increased digital pulses.

Therefore, further targeted owner education is required to raise awareness of the clinical signs that have actually been shown to be most commonly associated with laminitis, rather than those commonly perceived to be present.

Providing owners with a list of potential clinical signs to be aware of – including questions relating to management and clinical history of their animals – could encourage more rapid and proactive decision‑making.

Owner education could further be targeted to owners lacking previous direct experience of the disease and those owning breeds not perceived to be at risk.

Treatment involves providing analgesia and foot support, as well as treating the underlying endocrinopathy or primary condition causing sepsis-associated laminitis or SLL. Additionally, cryotherapy is indicated in certain circumstances.