14 Jul 2021

Source: EquiFluNet.

As an endemic infection in the UK and many other countries, equine influenza (EI) continues to be responsible for viral respiratory disease outbreaks in Europe and elsewhere in the world.

As is the case with most endemic diseases, outbreak frequency varies over time, and this variation may be due to a combination of host, environment and viral factors. Ongoing epidemiological research to monitor outbreaks is fundamental to maintaining optimal control and preventive measures.

In the UK, a dedicated EI surveillance initiative funded by the Horserace Betting Levy Board (HBLB) was formerly in place, and overseen by epidemiologists and virologists at the AHT. This scheme enabled subscribing veterinary surgeons to submit samples for testing from horses with clinical signs consistent with EI infection, with the laboratory costs covered by the HBLB.

With the recent re-establishment of the EI programme at the University of Cambridge Department of Veterinary Medicine, under former AHT virologist Neil Bryant, the HBLB-funded EI testing scheme is being reintroduced, with samples submitted for testing at Rossdales Laboratories.

Positive samples are then passed on to Dr Bryant for further characterisation and contribution to global surveillance. In addition, any laboratories confirming cases of EI in the UK are encouraged to continue to also report positive results and epidemiological information through the former AHT’s disease surveillance group, which continues to be supported by the Thoroughbred racing and breeding industry. Details of the EI testing programme, as well as how other laboratories with positive samples can submit samples to Dr Bryant, are available via email at [email protected]

Epidemiological information obtained is used to inform stakeholders and for research purposes. If an increase in outbreaks is noted, factors for this increase would need to be investigated. In understanding reasons behind increases in EI activity, control and preventive measures can be more effectively applied.

During 2019, the environmental factors of increased horse movements and the mixing of infected with susceptible animals in the late spring and summer months were considered important in aiding viral spread. Outbreaks were particularly evident following horse gatherings that did not mandate EI vaccination as an entry requirement or have a biosecurity policy in place.

Viral factors are also analysed by researchers, such as Dr Bryant, who monitor genetic changes in the virus, and compare them through space and over time. If analysis demonstrates a new variant is circulating, current vaccines must be evaluated to determine if the EI viral strains they contain continue to be cross-protective against the current outbreak strain.

When viruses evolve beyond vaccine capabilities for protection, large outbreaks can be seen, as was the case in 2003 in the UK. With vaccine updates potentially taking many years to reach end users, it is paramount to detect and evaluate important viral changes quickly when they are first emerging, to continue to monitor them closely, and to allow the required vaccine developments and updates in as timely a manner as possible. This highlights the importance of ongoing surveillance and how veterinary surgeons attending horses day to day are critical to this effort, through contributing samples for diagnostic testing and any positives contributing valuable surveillance data.

The information box at the end of the article includes details on how veterinary surgeons can register to receive alerts and messages on equine infectious diseases, and where to access further information online generated by the industry-supported disease surveillance group.

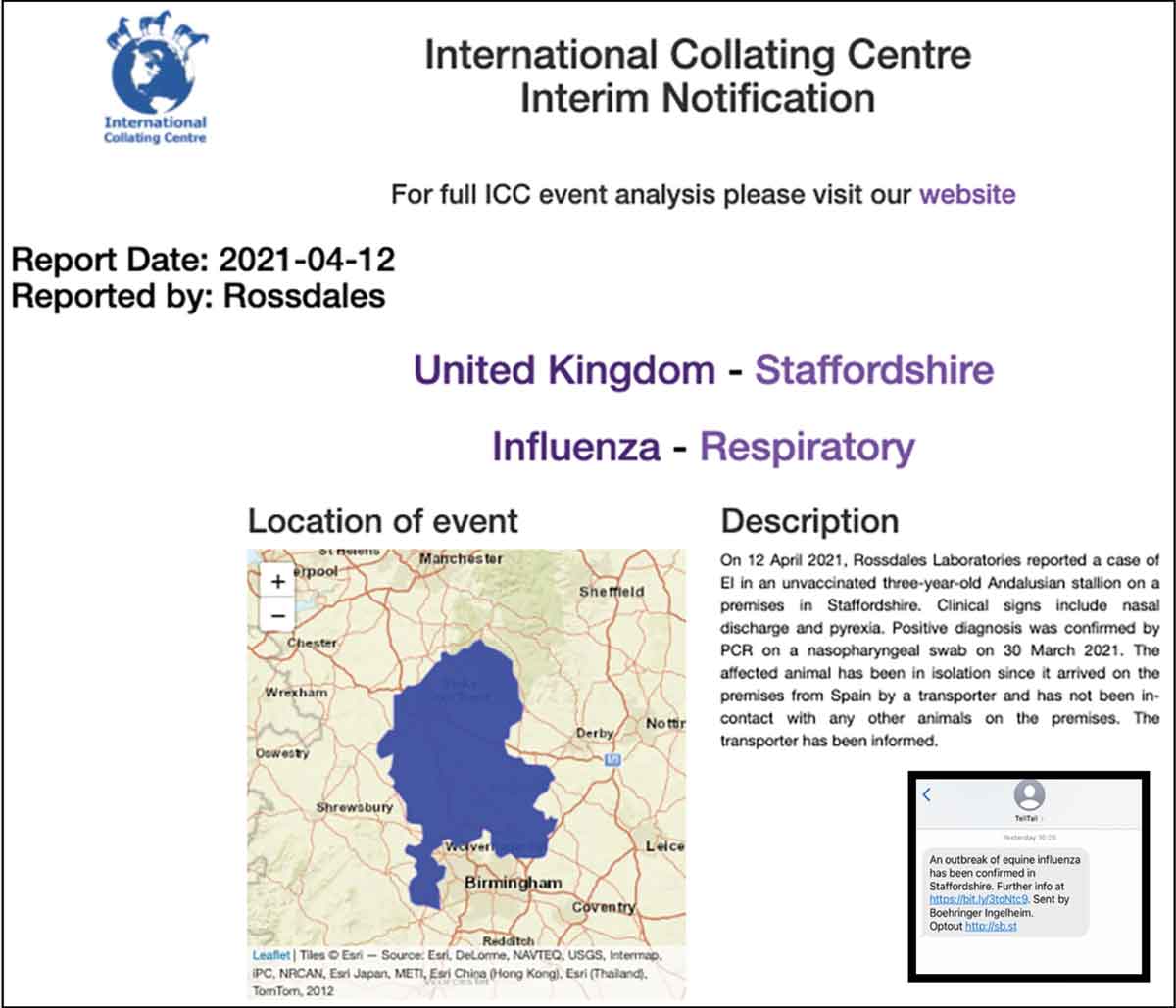

Outbreak information obtained through the surveillance network is reported by the International Collating Centre (ICC). The ICC reports on international infectious disease outbreaks on a near-daily basis, by email, to subscribers. An online interface is also available, and this enables information on international infectious disease outbreak reports to be evaluated in multiple formats, and a site solely displaying EI reports is also available separately.

Veterinary surgeons are also encouraged to sign up to receive Tell-Tail text message alerts for equine infectious disease reports in the UK, sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim. Each text message alert (Figure 1) contains a brief report and a link to a fuller outbreak report on the ICC website.

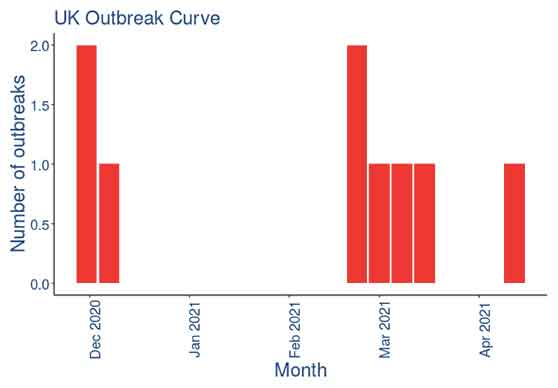

Between December 2020 and mid-April 2021, nine UK outbreaks of EI were reported through the ICC and Tell-Tail text message alert systems. Key epidemiological information for each outbreak is summarised in Table 1.

| Table 1. A summary of the epidemiological information for UK outbreaks of EI reported by the International Collating Centre for 1 December 2020 to 12 April 2021 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date of report | Location | Details of cases confirmed by laboratory testing | Diagnostic tests | Additional horses reported to have clinical signs | Reported clinical signs | In-contacts | Additional information | Virological information |

| 1 December 2020 | Lancashire | An unvaccinated two-year-old non-Thoroughbred | PCR on an NP swab | Not reported | Cough, mucopurulent nasal discharge, pyrexia, conjunctivitis | Not reported | Confirmed cases imported from the Netherlands and presented with clinical signs a few days after arrival | Florida Clade 1 EI virus |

| 4 December 2020 | Cheshire | An unvaccinated two-year-old non-Thoroughbred | PCR on an NP swab | One other horse | Cough, nasal discharge | 35 in-contacts; 10 of these were vaccinated | Both horses with clinical signs were new arrivals | *Pending |

| 9 December 2020 | North London | An unvaccinated non-Thoroughbred | PCR on an NP swab | One other horse | Cough, nasal discharge, mild pyrexia | 10 unvaccinated in-contacts with no clinical signs at time of reporting | Two new arrivals and both developed clinical signs two days after arriving | *Pending |

| 23 February 2021 | North Ayrshire | An unvaccinated eight-month-old non-Thoroughbred | PCR on an NP swab | Other horses on premises reported to have similar clinical signs | Cough, nasal discharge, pyrexia | 20 to 40 in-contacts | None | *Pending |

| 25 February 2021 | Somerset | A five-year-old non-Thoroughbred that had received a first vaccine 17 days before diagnosis | PCR on an NP swab | Eight other unvaccinated horses were mildly off colour with nasal discharges | Cough, nasal discharge, pyrexia, lymphadenopathy | 8 in-contacts | New arrival several days before clinical signs developed in the confirmed case | Florida Clade 1 EI virus |

| 2 March 2021 | Wiltshire | An unvaccinated three-year-old non-Thoroughbred | Not reported | None | Persistent cough, mucopurulent nasal discharge, pyrexia, lymphadenopathy | Several, recently vaccinated and unaffected in-contacts | Private premises. Affected case was a new arrival from Ireland and travelled via Northern Ireland | *Pending |

| 10 March 2021 | Midlothian | A vaccinated (complete primary course end of October 2020) 10-year-old non-Thoroughbred | PCR on an NP swab | No other horses reported to have clinical signs | Pyrexia, nasal discharge, inappetence, lethargy, lymphadenopathy | 20 to 30 vaccinated in-contacts | None | *Pending |

| 19 March 2021 | Essex | Two vaccinated three-year-old non-Thoroughbreds | PCR on an NP swab | None | Nasal discharge, pyrexia | 24 and 20 of these were fully vaccinated | One new arrival from mainland Europe two weeks previously, but placed in isolation on arrival and subsequently developed a nasal discharge. Tested negative to EI and EHV-1 | *Pending |

| 12 April 2021 | Staffordshire | An unvaccinated three-year-old Andalusian colt | PCR on an NP swab | No in-contacts | Nasal discharge, pyrexia | No in-contacts | The affected horse had been in isolation since arriving from Spain | *Pending |

| EI = equine influenza, EHV-1 = equine herpes virus-1, NP = nasopharyngeal, * = where results are pending, additional testing may be required prior to sequencing to determine strains; this can be due to a low amount of virus present in the submitted sample. | ||||||||

The majority of cases were unvaccinated and seven of the outbreaks had reported new arrivals in the preceding few days before clinical signs were noted. Further analysis by Dr Bryant confirmed a Florida Clade 1 virus was involved in the outbreaks reported on 1 December 2020 and 25 February 2021, as was the case in the UK and Europe 2019 epidemic. Further information on the strains implicated in other reported outbreaks in Table 1 will be released when analysis has been completed by Dr Bryant.

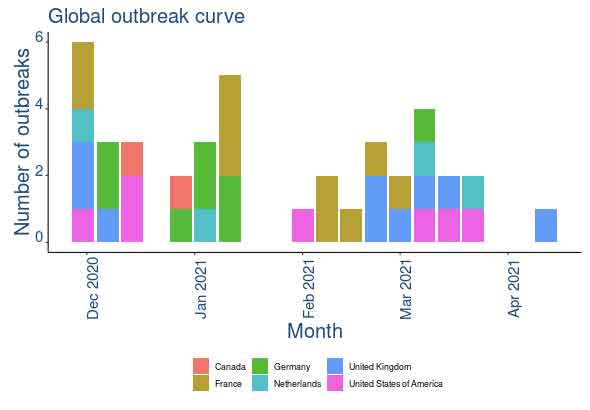

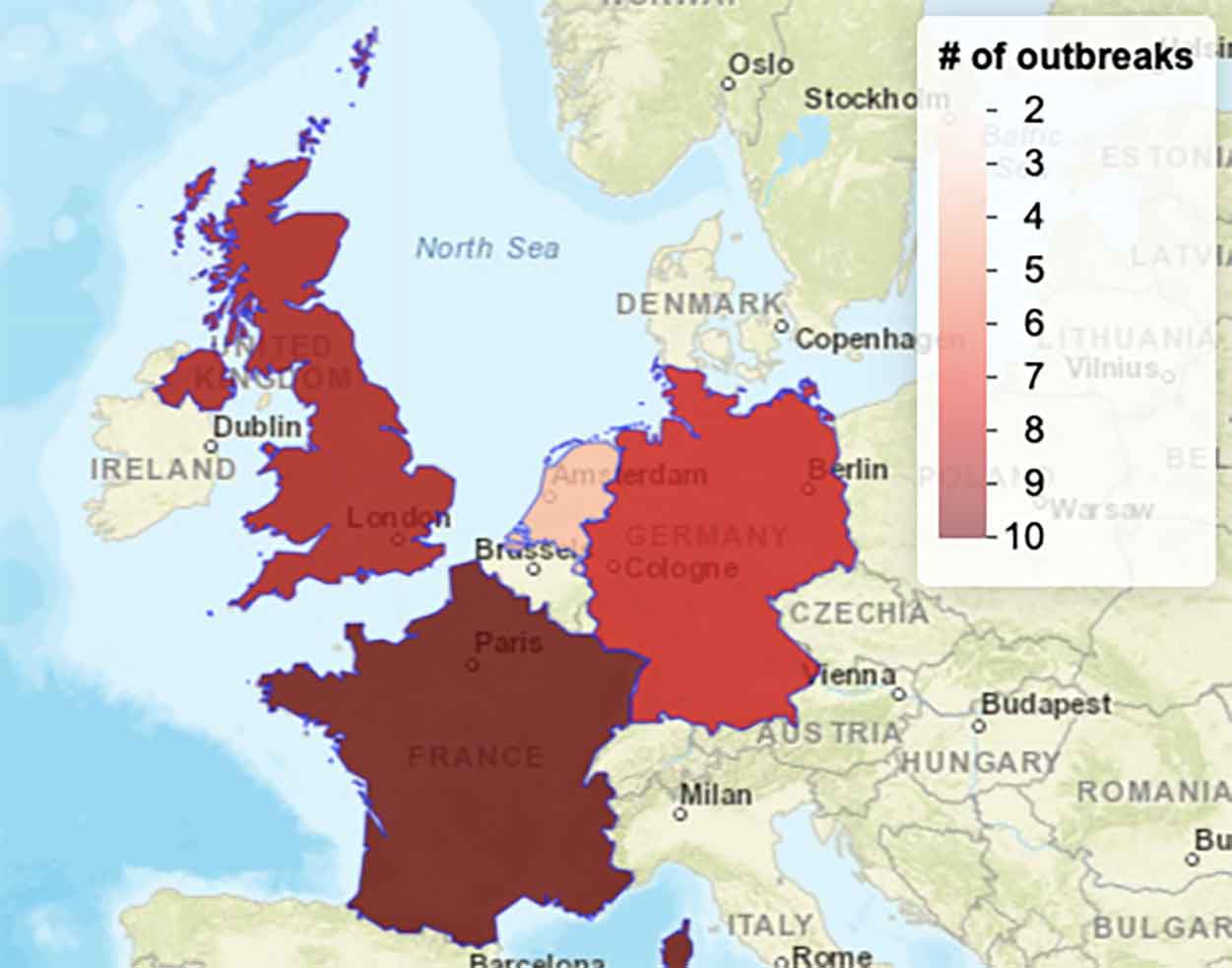

An outbreak curve demonstrates the frequency and timing of each outbreak report (Figure 2), and further information about EI outbreaks (Figures 3 to 5) can be obtained from EquiFluNet, which is specifically for EI outbreak reports.

Although EI is endemic in most countries worldwide, the number of reported outbreaks may not be a true reflection of the actual number of EI outbreaks a country actually experiences. This is because the outbreaks that reach the reporting stage are only those that have been subject to diagnostic testing by laboratories and that are then reported on systems that are monitored by the ICC.

A summary of known outbreaks is detailed in Table 2.

| Table 2. A summary of the number of outbreaks of equine influenza (EI) worldwide reported by the International Collating Centre for 1 December 2020 to 12 April 2021 | |

|---|---|

| Country or region | Number of reported EI outbreaks |

| Canada | 2 |

| France | 10 |

| Germany | 8 |

| Netherlands | 4 |

| UK | 9 |

| US | 7 |

| North America | 9 |

| Northern Europe | 31 |

| Total | 40 |

Messaging to encourage improvements in biosecurity by equine owners is needed. Awareness should be raised around a few key areas that have been previously demonstrated to facilitate spread of EI.

Veterinary surgeons play a very important role in educating horse owners and event organisers about infectious disease control and prevention. Measures should be in place to reduce the risk of infectious disease outbreaks to the lowest level possible, and, if outbreaks do occur, they should be detected quickly and effectively to limit their spread.

Develop a premises biosecurity plan with yard owners. By working with each one’s treating veterinary surgeon, yards can have a plan that is pragmatic, feasible, and relevant to its population and setup.

This plan should focus on:

The EI vaccination requirements of new arrivals should also be specified, with all ideally being two weeks beyond their second dose of the primary course or having received a booster dose within the past six months.

Following on from the high-profile equine herpes virus (EHV-1) neurological disease outbreaks in Spain in February 2021, judicious measures have been put in place for horses competing under International Federation for Equestrian Sports rules (https://inside.fei.org/fei/ehv-1/return-to-competition). Although designed for EHV-1, the protocols provide a good example of the measures and precautions all equine event organisers should be taking. As a minimum, protocols should include:

Following events, horses are at higher risk of suffering from an infectious disease. Precautions include quarantining of horses on return after events and owners being encouraged to closely clinically monitor them for up to two weeks, as outlined earlier.

Being endemic in most countries worldwide – and given the potential for antigenic drift, and even shift of the virus and occasional cross-species transmission – EI is a constant threat to our equine population.

Through the UK-based Thoroughbred industry-funded surveillance system, essential information from outbreaks can be obtained to help understanding of how the virus is behaving, and this information is correlated with host and environmental factors. From this, monitoring, control and prevention measures can be optimally designed and implemented.

Veterinary surgeons have an integral role in ensuring the success of this necessary surveillance, through sampling suspect cases in the field and submitting samples to diagnostic laboratories with a full history detailed on the laboratory submission form. Assistance with optimal samples to take and outbreak control measures can be provided by equine epidemiologists.