11 Mar 2025

Image: © callipso88/ Adobe Stock

The rising emergence of equine infectious diseases – driven by pathogen adaptation, climate change expanding the range of disease vectors and the growing national and international movement of horses – has underscored the critical need for robust disease surveillance systems.

As explored in the first article of this series1, these systems have developed over time in response to evolving disease scenarios and industry needs, becoming vital for safeguarding horse health and welfare, and ensuring the sustainability of the equine industry in the UK.

Building on this foundation, this second article focuses on the essential role of communicating surveillance outputs, outlines current surveillance developments and addresses the specific challenges that may lie ahead.

Effective communication ensures that stakeholders – from veterinary professionals to horse owners and policymakers – are informed about diseases and their epidemiology, are aware and respond to threats through the implementation of biosecurity measures, and are prepared to participate by making surveillance contributions for the benefits of themselves and the wider population. Equine Infectious Disease Surveillance (EIDS) communicates surveillance findings through various formats to ensure timely dissemination and stakeholder engagement.

One of the key communication channels is the International Collating Centre (ICC), which has been operating for more than 35 years and is managed day to day by EIDS.

The ICC collates and disseminates international equine disease outbreak alerts with case information primarily gathered from country-based infectious disease reporting systems, such as the US’ Equine Disease Communication Center and France’s RESPE initiative (Figure 1). These reports usually involve cases confirmed through laboratory testing that have either been submitted directly by the diagnostic laboratories or voluntarily reported by veterinary surgeons.

The ICC reporting system provides real-time interim reports, emailed to subscribers on an almost daily basis, and an interactive ICC website is available where users can query data by time frame and by countries and their regions, globally.

Additionally, EIDS produces a static quarterly summary report, available on the EIDS website, with a brief overview of this also featured in the Equine Quarterly Disease Surveillance Reports (EQDSR).

The EQDSR is produced by EIDS, on behalf of Defra, the APHA and BEVA (Figure 2). The report is available quarterly and presents detailed analyses of equine surveillance data, including equine influenza, equine herpes virus (EHV), strangles, equine grass sickness and cyathostominosis. It also features UK laboratory testing surveillance data, awareness-raising news articles and educational content through focus articles.

Subscribers can receive a link to the report on the EIDS website each quarter by email, and the report is also published in an abridged format in the Veterinary Record journal – reading either version contributes to veterinary CPD requirements.

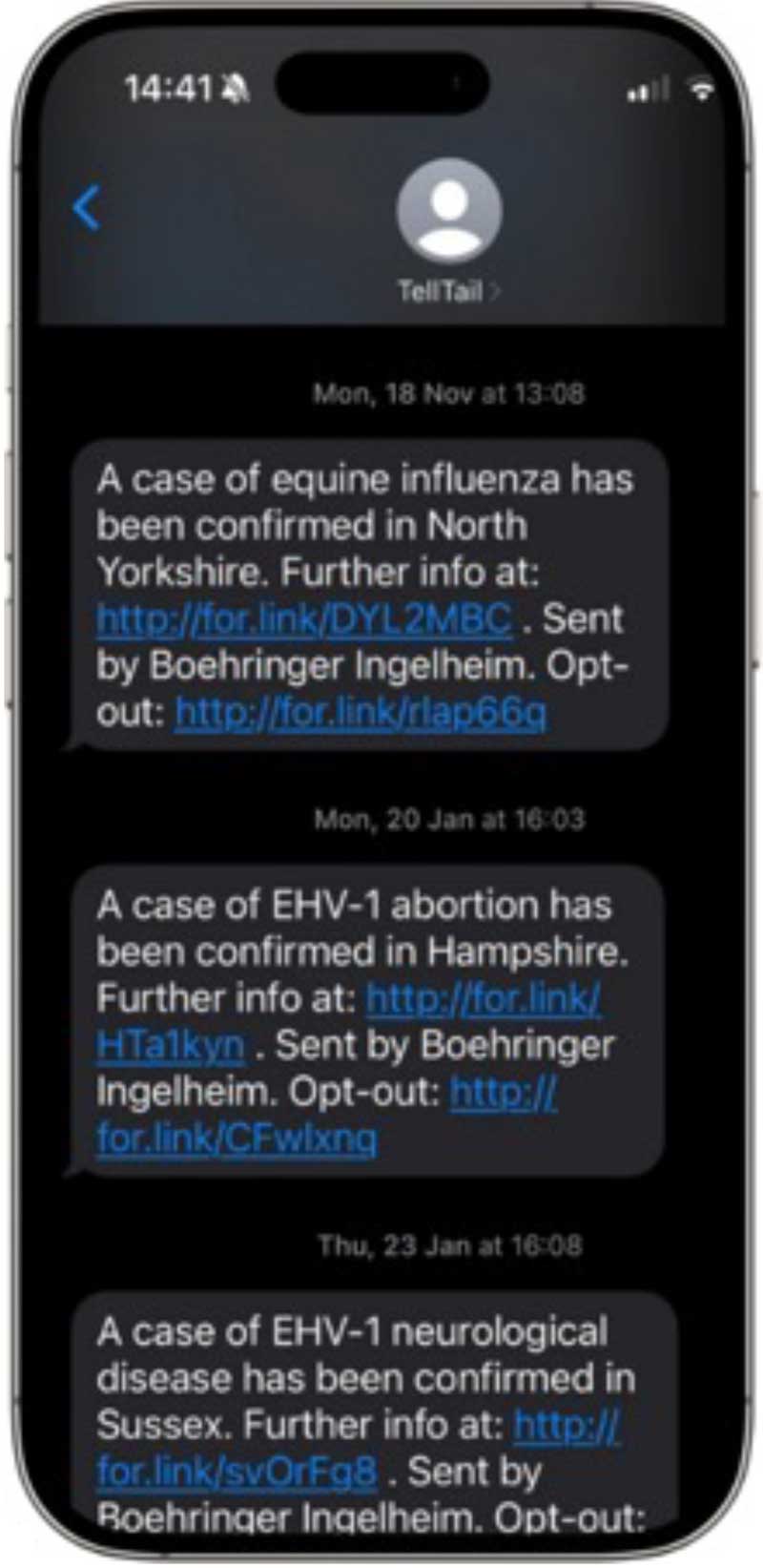

For rapid disease updates, veterinary professionals in the UK can sign up to the Tell-Tail text message alert system. The scheme is sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health and delivers near real-time notifications on urgent disease outbreaks based on UK ICC alerts for outbreaks of equine influenza, EHV-1 neurological/abortion/neonatal death and notifiable equine diseases (Figure 3).

EIDS also manages several disease-specific interactive online platforms that are accessible via the EIDS website.

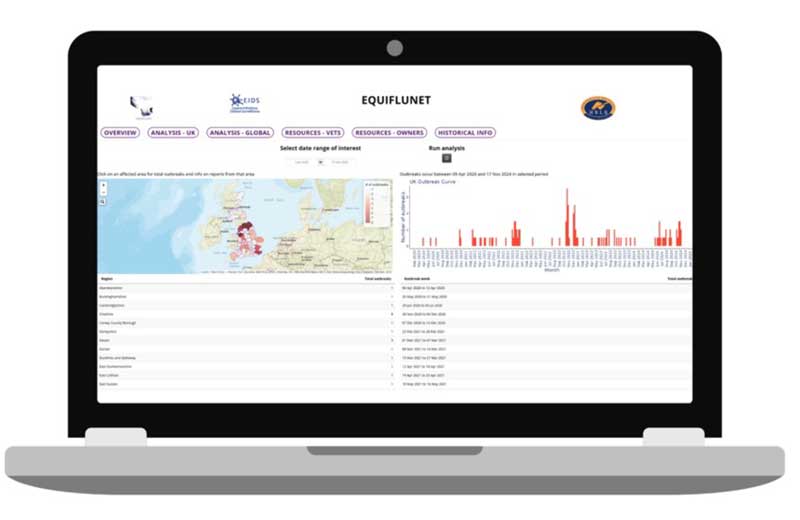

EquiFluNet has provided insights into UK and global equine influenza diagnoses since 2019, featuring disease density maps based on UK counties and outbreak curves for user-selected date ranges (tinyurl.com/5csux47u; Figure 4).

All data on this platform are also reported through the ICC, with UK-based reports also shared through the Tell-Tail text message alert system.

Another interactive platform is from the Surveillance of Equine Strangles (SES) network, which enables users to explore SES surveillance data reported regarding laboratory diagnosed cases of strangles over a user-defined date range (Figure 5).

Data reported includes case signalments, clinical signs, diagnostic methods requested by submitting veterinary surgeons and locations of diagnosing veterinary practices mapped to UK counties (tinyurl.com/5xhva5nb).

As part of ongoing efforts to enhance the effectiveness of disease surveillance, EIDS is working on a number of projects.

A new database has been developed for data acquisition and storage of the quarterly laboratory surveillance data collected for the EQDSR laboratory surveillance section. This has enabled improved data quality through finessing data collection methods and analysis of data across quarters and years.

This new system enabled a recent publication that investigated the increasing trend in faecal worm egg count positivity rates over a 17-year period2. An online platform is in development that will provide an interactive interface for users to explore and analyse these laboratory surveillance data. The platform aims to offer insights into trends in data and allow users to query data on the basis of specific parameters, thereby improving the accessibility and utility of laboratory surveillance information.

Alongside this, a database has been developed for improving postmortem examination (PME) surveillance, with retrospective data inputted from previous EQDSR reports, and data are now also being collected prospectively in the new system. The PME diagnoses have been captured using the veterinary nomenclature “VeNom” coding system (tinyurl.com/4mpa4bbx), with the PME database designed to capture multiple diagnoses per case, diagnostic certainty levels and relevant diagnostic methods.

Inspired by the Veterinary Investigation Diagnosis Analysis system used by the APHA, near real-time data sharing by the network of centres that contribute PME data to the EQDSR will be encouraged. These advancements in UK equine postmortem surveillance tools will allow for greater flexibility in data analysis, more comprehensive disease monitoring, and more efficient communication of findings, ultimately leading to improved equine health and welfare.

EIDS collaborates with key organisations to expand the scope of equine disease surveillance efforts. This includes collaborating with the University of Liège on promoting its dedicated Atypical Myopathy Alert Group (AMAG), with EIDS encouraging UK-based vets to report cases of atypical myopathy seen in this country to AMAG.

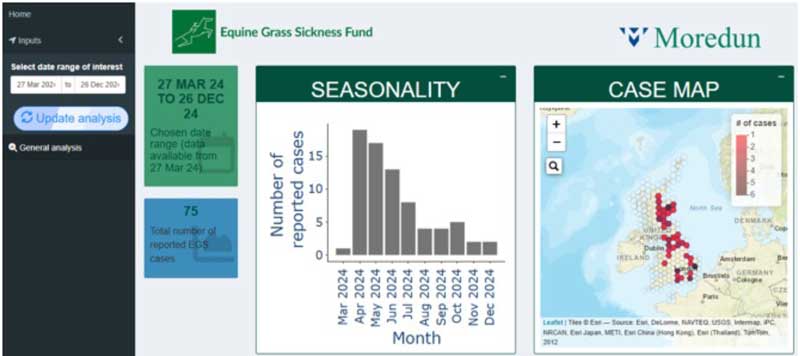

Additionally, a close collaboration with the Moredun Foundation Equine Grass Sickness Fund is supporting the monitoring and surveillance of equine grass sickness (EGS) in the UK, with EIDS actively encouraging reporting of cases to this surveillance system.

As part of this initiative, EIDS is sharing EGS case reports through the ICC, and a quarterly summary of cases across the UK is published in the EQDSR. The EGS Fund has recently launched an interactive online platform for the surveillance of EGS, which allows users to access and investigate data on EGS cases, including temporal and spatial distributions of EGS case reports (Figure 6).

In time, the data being made available from the EGS Fund will be extended retrospectively and its scope expanded. As such, the platform will greatly enhance information available on EGS’ prevalence, seasonality, geographical distribution across the UK and other risk factors, thereby improving real-time awareness and prospects for implementing timely disease management strategies.

In response to industry concerns around the potential for increasing parasite-related clinical disease, as a result of a reduction in the use of anthelmintics to combat resistance, EIDS recently launched a new initiative called RedWatch.

This is a surveillance platform for veterinary surgeons to report cases of clinical disease attributed to cyathostominosis or large strongyles. The platform aims to monitor disease prevalence and identify risk factors to advance our understanding of parasite-related disease.

For cyathostominosis, in particular, if surveillance submissions are sufficient over time, the opportunity may arise for developing a warning system similar to the sheep Nematodirus Forecast tool produced by the Sustainable Control of Parasites in Sheep group, which, once available, could help proactively guide improved equine disease control strategies.

As part of a Horse Trust-funded PhD research project, the SES network was able to also operate as an enhanced surveillance network, spanning the period between 2016 and 2022, inclusively. This enabled a biobank of Streptococcus equi isolates recovered from predominantly clinical strangles cases located across the UK, to be curated over the seven years.

The biobanked samples were then subjected to DNA extraction and whole genome sequencing (WGS), enabling molecular epidemiological analysis of UK strangles cases. Analysis of the genomic population grouping and transmission of these WGS S equi isolates showed a marked and statistically significant (p<0.001) change in the relative proportion of strain groups over the period. Transmission analyses provided examples of both localised as well as widely geographically distributed transmissions of genetically related S equi.

The relatively rapid change in strain group distributions within the surveyed S equi population and genomic links inferring chains of transmission has provided novel insights into the epidemiology of strangles in this country since 2016.

As described, EIDS continues to collate epidemiological data through the SES initiative, although following the completion of the funded research project, the collection and genome sequencing of UK S equi isolates ceased at the end of 2022.

If funding from the equine industry could be found, reinstating a biobank and WGS of S equi isolates from UK strangles diagnoses that have case details registered on SES would be epidemiologically highly desirable, as it would facilitate prospective genomic surveillance of S equi.

This form of enhanced surveillance has been proven and would be particularly relevant currently following the launch in 2022 of Strangvac (Intervacc), an exciting new strangles vaccine. The ability to monitor the impact of Strangvac on the frequency, distribution, clinical presentation and genomics of S equi as take up of the vaccine increases, would be unprecedented in equine surveillance.

In particular, the genomic data would facilitate monitoring emergence of variant strains of S equi and would help inform future needs for updates to the recombinant protein components of Strangvac.

Addressing the challenges faced in bridging the gaps between data collection, dissemination of useful information and actionable disease management strategies is essential to ensure surveillance continues to evolve to meet the demands of a changing disease landscape.

Effective surveillance is critical for detecting emerging threats such as novel diseases, and the related issues of increasing antimicrobial and anthelmintic resistance (AMR; AHR).

These phenomena all present significant ongoing risks and, as cross-species and zoonotic disease transmissions become increasingly apparent, they require continuous adaptation of surveillance frameworks to safeguard not only equine health, but wider animal and human health.

While equine disease surveillance in the UK has made significant strides, key challenges still exist to address.

EIDS is currently operating under a short-term contract that is almost exclusively funded by the Thoroughbred sector, creating a need for continued stability and support to maintain effective surveillance.

Securing additional financial backing from other equine industry sectors is crucial to ensure long-term sustainability, maintain a comprehensive, population-wide approach, and lead to an increased sense of collective responsibility for the well-being of the UK equine population relating to infectious diseases.

Current surveillance data sources rely on traditional laboratory-based surveillance methods for disease identification, which, while effective, face several challenges. These methods require multi-stakeholder engagement (owner/keeper, veterinary surgeon, laboratory) and suffer from delays, non-responses, or declines in providing information for anonymised reporting.

Additionally, they can be time consuming for all parties involved and may result in missed critical data. Relying solely on diagnostic sample collection as a primary surveillance method has limitations, being dependent on veterinary involvement in sample collection and correct decisions on sample type, test choices and successful laboratory testing. The costs associated with diagnostic tests and veterinary services may also restrict the number of samples collected and tested. Additionally, concerns over stigma surrounding infectious disease diagnoses may contribute to under-reporting.

Initiatives aimed at making laboratory testing more affordable for owners, such as the Horserace Betting Levy Board-funded (HBLB) equine influenza surveillance scheme, help to address financial barriers by covering the costs of laboratory testing. Successful surveillance also requires that test results are accurately obtained by testing facilities, yet laboratory participation in formal quality assurance accreditation schemes is not mandatory in the UK, though many laboratories voluntarily comply.

Furthermore, surveillance faces an unavoidable lag phase as samples are collected, submitted to laboratories, and results are processed. The most significant challenge in the surveillance process, however, remains in EIDS receiving communication and permissions via the testing laboratory from the treating veterinary surgeons and their clients.

Without this, cases will not appear in surveillance reports or alerts, and enhanced surveillance for monitoring pathogen strains and informing vaccine design is not possible. Given the current design of surveillance systems requiring inputs from veterinary surgeons to ensure their success, increasing awareness and engagement among veterinary surgeons nationwide remains a priority.

The advancement of point of care (POC) agent detection testing modalities, based mainly on variations of the long-established PCR method, such as loop-mediated isothermal amplification and insulated isothermal PCR, provides promising opportunities for readily accessible and rapid diagnoses.

However, for surveillance, overseeing networks based on POC testing that are decentralised, into individual practice-based or even practitioner-based settings, presents additional challenges and could readily increase rather than decrease surveillance gaps. To address this, the systematic sharing of summary data, such as the number of tests conducted and the number of positive results detected, with EIDS’ surveillance initiatives is being explored and encouraged.

EIDS also encourages veterinary practices employing these tests to endeavour to collaborate with the group’s ongoing surveillance initiatives by providing anonymised case and diagnostic details from positive POC assays, thereby complementing existing diagnostic laboratory disease surveillance.

The use of syndromic surveillance follows the general principles of utilising continuously acquired pre-diagnostic data, contributing to situational awareness and better informing decision making.

While laboratory-based surveillance is limited to information gathered at the reporting stage, syndromic surveillance can use multiple channels to gather and analyse data, such as electronic health records held on practice management systems (PMS), online data mining, general public reporting and geographic information systems.

Although syndromic surveillance may appear to be a less-accurate method, it has the advantage of improved timeliness of alerts, which is important for vigilant horizon scanning. Syndromic surveillance could play a pivotal role in the early detection of emerging diseases or detecting notable trends. By swiftly recognising deviations from the norm in disease patterns or clinical signs, this surveillance mechanism can trigger a comprehensive investigative pipeline.

This pipeline will be instrumental in rigorously evaluating the potential risks associated with any newly identified or emerging infectious diseases within the UK equine population.

Such proactive measures are essential for timely intervention and effective management to safeguard equine health and welfare nationwide.

Within the UK, two syndromic surveillance initiatives partner with some, but not all, equine veterinary practices across the UK; however, equine clinical records may not always include detailed information – particularly where electronic records are primarily required for client billing purposes.

The Equine Veterinary Surveillance Network is overseen by the University of Liverpool and follows the approach developed by SAVSNET; Equine VetCompass is based at the RVC and follows the approach taken to small animal syndromic surveillance.

Equine syndromic disease surveillance will remain challenging until clinical record keeping improves among equine veterinary surgeons, and currently EIDS does not have access to this information or have communication systems in place with the projects should concerning patterns of clinical presentations arise. For diseases that include more generalised clinical signs, such as equine respiratory diseases that can include pyrexia, nasal discharge and lethargy, the use of syndromic PMS scanning or general public reports may over-estimate incidents of certain diseases.

In these cases, surveillance systems benefit from accurate diagnoses and reports through the capture of laboratory data. Consequently, the majority of surveillance schemes for equine infectious diseases within the UK should continue to comprise laboratory surveillance projects.

The evolution of equine infectious disease surveillance in the UK reflects the growing complexity of the challenges faced by the equine industry, as well as the ongoing need for robust, adaptable and comprehensive monitoring systems.

While historical surveillance efforts have significantly advanced our understanding of equine disease dynamics and led to effective control measures, the emergence of new diseases, changing climate conditions, and increasing horse movements nationally and internationally, demand continuous adaptation of surveillance strategies.

As we move forward, the integration of innovative methods such as syndromic surveillance and improved and more accessible diagnostic capabilities will be crucial for enhancing real-time monitoring, and early detection of emerging diseases.

Equine infectious disease surveillance is not without its challenges, including issues related to data completeness and the sustainability of funding. Crucially, the lack of engagement from stakeholders, such as veterinary surgeons, in recognising the importance of their contributions to surveillance remains a significant barrier to optimising programme outputs and staying proactive in addressing emerging and evolving diseases.

A major challenge also lies in the stigma surrounding certain diseases, which can discourage reporting and proper implementation of biosecurity measures for disease control and prevention.

To overcome these obstacles, further research into behaviours and attitudes towards infectious disease is needed.

By addressing the root causes of poor engagement and promoting better understanding of the importance of surveillance and biosecurity, the equine industry can improve its collective response to infectious diseases. Collaboration between veterinary professionals, researchers and industry stakeholders is key to strengthening the surveillance framework.

The future of equine disease surveillance lies in combining traditional methods with new technologies, ensuring that the system remains agile and responsive to emerging threats.

With continued investment in surveillance infrastructure, research and behaviour change efforts, the UK equine industry will be better positioned to manage the risks posed by infectious diseases, safeguarding the health of horses and maintaining the resilience of the sector.

Resources and interactive platforms

Sign up to all the surveillance initiatives mentioned in this report on the EIDS website under the sign-up tab: tinyurl.com/4zfvvvbw

The International Collating Centre: tinyurl.com/2u747zhp

EquiFluNET: tinyurl.com/5csux47u

Surveillance of Equine Strangles: tinyurl.com/5xhva5nb