9 Jun 2020

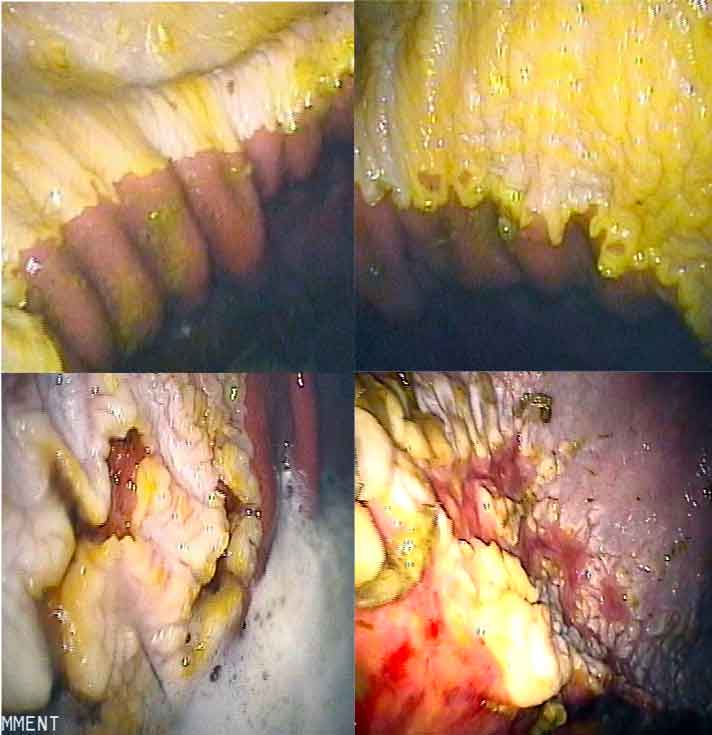

Figure 1. Gastroscopy is required for the diagnosis of equine gastric ulcer syndrome.

A great deal of effort has been made in the past few years to clarify the terminology associated with equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS).

This has been predominantly driven by the recognition that EGUS can be separated into two distinct syndromes, based on the area of the stomach affected. It is generally accepted that EGUS should be classified as equine squamous gastric disease (ESGD) or equine glandular gastric disease (EGGD).

The underlying pathophysiology for both syndromes is different. The main factors associated with ESGD are related to excessive exposure of the squamous mucosa to hydrochloric acid, volatile fatty acids, bile acids and pepsin.

The pathophysiology of EGGD is less well understood, but failure of the mucosal barrier is thought to be the major factor predisposing to disease. Alterations in local mucus, bicarbonate and prostaglandin production, in addition to changes in blood flow, are likely to be important.

Once the mucosal barrier is compromised then exposure to acid may amplify disease. In some horses, EGGD may be part of a more generalised syndrome of inflammatory bowel disease.

Based on the differing aetiologies, the risk factors for both syndromes are slightly different. These are summarised in Table 1.

| Table 1. Risk factors for equine gastric ulcer syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Risk factors for equine squamous gastric disease | Risk factors for equine glandular gastric disease |

| Intermittent fasting | Regular exercise (more than four days a week) |

| High-starch diet | High-starch diet |

| High-intensity exercise | Stress |

| Stress | NSAID use |

| Lack of access to pasture or forage | Warmblood breed |

The prevalence of EGUS varies between different populations.

It is generally accepted that the prevalence of ESGD is quite high in certain groups of horses in which the risk factors are difficult to control. The reported prevalence is about 90% in racehorses in training, and between 20% and 60% in other disciplines.

In the author’s experience, the prevalence in racehorses may be slightly lower than this as trainers have increased their awareness of EGUS and focus on dietary management.

The reported prevalence of EGGD is very variable – between 8% and 71% – but generally considered to be higher in horses that are working frequently or experiencing high levels of stress. The intensity of exercise seems to less important than the frequency of exercise in the predisposition to EGGD.

Dietary factors are frequently discussed, and it is generally considered that lack of access to pasture or forage – and a high-starch diet – are risk factors, but very little published evidence exists to support this.

Warmbloods are generally considered to be at an increased risk of EGGD. Specific management factors – such as individual trainer and multiple horse carers – may also have a role in increasing stress and risk in some individuals.

Clinical signs of EGUS are variable – and this can make diagnosis a challenge.

Reported clinical signs include inappetence, colic, weight loss, poor body condition, poor performance, sensitivity to girthing and abnormal behaviour under saddle.

Some horses with EGUS appear asymptomatic. In the author’s experience, often no association exists between the presence of EGUS and clinical signs, such as sensitivity to girthing or grooming, or bad behaviour.

In general, it seems horses with more severe EGGD are more likely to demonstrate clinical signs, such as colic, inappetence and weight loss. However, this may be a reflection that EGGD can be a component of more generalised gastrointestinal disease.

Diagnosis of EGUS relies on gastroscopy (Figure 1). Other tests – such as the sucrose absorption test and faecal occult blood test – have seen a great deal of interest to make a diagnosis. However, these tests generally have a low sensitivity and do not provide information about the severity of disease or the location of lesions.

A recent study has evaluated the use of oxidative biomarkers as a diagnostic tool, but concluded this area will require further work.

Gastroscopy can be safely carried out in the sedated standing horse using a 3m long endoscope. To allow adequate visualisation of both the squamous and glandular mucosa, feed should be withheld for between 8 hours and 12 hours prior to the procedure.

Few complications are associated with the procedure, although epistaxis can sometimes occur. One study reported colic in 2.9% of 573 horses following gastroscopic procedures, with one horse requiring exploratory laparotomy for small intestinal volvulus.

Ulcers should be graded or described based on their location (Table 2).

| Table 2. Recommendations for ulcer grading/description | |

|---|---|

| Equine gastric ulcer syndrome – Equine Gastric Ulcer Council grading system | Equine glandular gastric disease – descriptive terminology based on European College of Equine Internal Medicine consensus |

| 0 Intact epithelium | Cardia, fundus, antrum, pylorus |

| 1 Intact epithelium, evidence of hyperaemia or hyperkeratosis | Focal, multifocal, diffuse |

| 2 Small, single or multifocal lesions | Nodular, raised, flat, depressed |

| 3 Large, single or multifocal lesions, or extensive superficial ulceration | Erythematous, haemorrhagic, fibrinosuppurative |

| 4 Extensive lesions with areas of deep ulceration | |

Treatment of EGUS should consider two areas: medication and management or reduction of possible risk factors.

As ESGD (Figure 2) is predominantly caused by excess exposure to acid, medical treatment predominantly relies on the use of acid‑suppressive medication.

Omeprazole remains the drug of choice for acid suppression. Omeprazole is a proton pump inhibitor that blocks the hydrogen‑potassium pump.

The formulation of omeprazole is very important as the drug is inactivated by stomach acid. The drug must be in an enteric coated formula to enable passage through the stomach to be absorbed. A number of enteric coated paste formulations are licensed for the treatment of ESGD.

The dose of oral omeprazole needed for treatment of ESGD has been debated over recent years. Initial studies all evaluated a 4mg/kg dose, whereas more recent studies have shown ulcer healing can sometimes be achieved using a lower (1mg/kg or 2mg/kg dose).

Individual variation appears to exist in the bioavailability of oral omeprazole, but forage feeding also seems to reduce bioavailability.

The most reliable absorption of the drug appears to occur in horses that have been fasted and are given the drug between 30 minutes and 60 minutes prior to feeding. This can practically be achieved by most horse owners if the drug is administered first thing in the morning, as most horses will naturally finish feeding by the late evening and fast until morning.

Prolonged acid suppression (pH greater than four for 12 hours) is more likely to be achieved using the 4mg/kg dose, but, in some horses, can be achieved using a lower dose.

If a lower dose is used (sometimes considered a “preventive” dose) then attention should be paid to maximising absorption by administering after fasting.

Omeprazole can also be used in an injectable formulation and studies have shown this can be an effective treatment for ESGD. The injectable formulation causes reliable and prolonged acid suppression in most horses. However, as the oral formulation is licensed for the treatment of ESGD, this should be used in preference, except in exceptional circumstances.

Histamine receptor antagonists are sometimes proposed for treatment of ESGD, but they are generally unreliable and cause inferior acid suppression.

Reducing or managing risk factors is an essential part of treatment for ESGD. This can be difficult in horses that remain in full training – in these horses, management of ESGD can be difficult, even with medication.

Dietary management should focus on maximising turnout or providing frequent access to forage. Concentrate feed should be minimised and split into multiple small meals.

Reducing exercise intensity can help, and horses should not be exercised on an empty stomach as a fibre mat of food is important to buffer the gastric pH and prevent acid “splashing” injury. Stress should be minimised as much as possible.

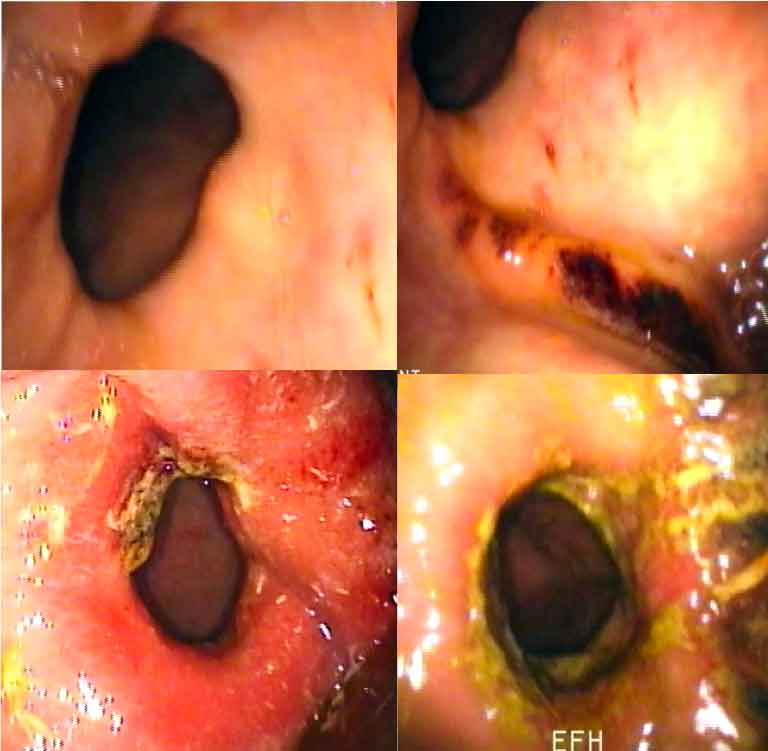

Multiple studies have shown that oral omeprazole is poorly effective for the treatment of EGGD (Figure 3) and is not recommended as a sole therapy.

Sucralfate is a drug that has been proposed for the treatment of EGGD. Sucralfate is an aluminium hydroxide salt that adheres to gastric mucosa. Its proposed mechanisms of action include provision of a physical barrier to acid, stimulation of local mucus and bicarbonate production, and stimulation of local blood flow by increased prostaglandin production.

Little evidence exists that sucralfate alone is an effective treatment, but a number of studies have evaluated the use of sucralfate and omeprazole in combination. The published success rates of this combination of drugs vary (roughly between 20% and 60%).

If this combination of drugs is used, it is recommended that a 4mg/kg dose of omeprazole is administered 8 hours after feeding, and between 30 minutes and 60 minutes before feeding; and that sucralfate is administered at least 30 minutes after the administration of omeprazole. This can be challenging to achieve in practice.

Misoprostol is a prostaglandin analogue. Its proposed mechanisms of action include acid suppression and inhibition of neutrophilic inflammation. A number of studies have shown misoprostol has reasonably good efficacy for the treatment of EGGD, and a recent study has shown the drug is more effective than the combination of omeprazole and sucralfate.

Misoprostol may compromise the effect of proton pump inhibitors and, consequently, it is not recommended that the drug is given in combination.

The drug is not licensed for use in horses and should be used following the prescribing cascade. Additionally, major safety factors exist that should be considered when prescribing this drug, as it can induce abortion in humans – consequently, it should not be handled by women who are pregnant or trying to become pregnant.

Injectable omeprazole is the most recent drug proposed for the treatment of EGGD. This drug causes greater and more prolonged acid suppression than oral omeprazole, and initial studies have shown very promising healing rates.

Studies that compare the effects of misoprostol and injectable omeprazole do not exist, so it is difficult to advise which drug should be considered for first line treatment.

Injectable omeprazole has significant advantages over misoprostol in terms of its frequency of dosing and lack of human health risks. However, injection site reactions seem to occur reasonably frequently and can be problematic. This drug should, again, be used following the cascade.

Antimicrobials have been proposed for some cases of EGGD. However, limited evidence exists to suggest they are effective and their use is not justified for the majority of cases.

Corticosteroids can be effective in horses in which EGGD seems to be part of a more generalised syndrome of inflammatory bowel disease. In horses with significant weight loss or more severe clinical signs, gastroscopy should be considered as part of a more thorough diagnostic investigation.

Other tests that should be considered include abdominal ultrasound, blood work and an oral glucose absorption test. Rectal and duodenal biopsies can also be useful in these cases.

Management recommendations for EGGD include ensuring at least two days a week rest from ridden exercise, minimising stress and careful dietary management.

Dietary recommendations generally include pasture turnout (if tolerated), limiting non‑structural carbohydrates and ensuring forage or chaff is fed prior to exercise. Some evidence exists that the provision of dietary oil, and the use of pectin and lecithin complexes, can be useful.

EGUS remains a common clinical problem in horses. Clinical signs are often non-specific and gastroscopy should be used for diagnosis. EGUS should be categorised into ESGD and EGGD.

A summary of treatment options is shown in Table 3. Oral omeprazole remains the treatment of choice for management of ESGD, but greater efforts should be made to advise how to administer the drug to maximise efficacy.

| Table 3. Treatment options for management of equine gastric ulcer syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Equine squamous gastric disease recommended treatments | Equine glandular gastric disease recommended treatments |

| Oral omeprazole (4mg/kg once daily) | Oral misoprostol (5ug/kg twice daily) |

| Oral omeprazole (1mg/kg or 2mg/kg once daily) | Injectable omeprazole (4mg/kg every five days to seven days) |

| Injectable omeprazole (4mg/kg every five days to seven days) | Oral omeprazole (4mg/kg once daily) in combination with oral sucralfate (12mg/kg twice daily) |

| All medications should be used in accordance with the prescribing cascade. | |

A number of treatment options are available for the management of EGGD, but oral misoprostol and injectable omeprazole are generally the best first line treatments.

In all cases of EGUS, efforts should be made to manage risk factors.