23 Nov 2021

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most common neoplasm of the equine stomach. It is most commonly found as a single, ulcerated, necrotic mass in the squamous gastric mucosa and has been associated with Equus caballus papillomavirus-21. Other gastric neoplasms reported in the literature include leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumour, papilloma, mesothelioma, adenocarcinoma and lymphoma.

The most consistent clinical signs are tachypnoea, decreased borborygmi and low bodyweight. Additional signs may include inappetence, weight loss, lethargy, hypersalivation, colic and fever. A large proportion of horses with gastric SCC are anaemic, and as with other tumours, some may also develop hypercalcaemia of malignancy2.

Historically, most cases of gastric neoplasia have been diagnosed relatively late (after metastasis), with little or no available treatment options, and typically only a few weeks’ survival. As the use of diagnostic modalities, such as gastroscopy and abdominal ultrasound, become more widely used, and equine oncology continues to develop, earlier diagnosis may make horses better candidates for treatment in the future.

Impaction of feed material in the stomach is most commonly seen secondary to abnormalities further down the intestinal tract, or associated with severe liver disease3. Rarely, primary gastric impaction is identified. Causes may include feeds that swell or stick together (for example, beet pulp or persimmons), poor dentition, inadequate water supply, poor feed quality or abnormal gastric motility.

Horses can present with varying degrees of acute, chronic or recurrent colic. In more stoic (particularly draft-type) horses and donkeys, the only clinical sign might be a decreased appetite and/or slightly increased recumbency. These mild signs may be all that precedes gastric rupture4.

Gastric impactions are treated with analgesia, fasting, rehydration, gastric lavage and carbonated drinks (which is remarkably effective). The author uses 250ml to 500ml of Diet Coke every two to six hours via nasogastric tube depending on how worried she is about gastric rupture.

Surgical gastrotomy should be a last resort, as the procedure is technically difficult (particularly in large adult horses), with a high likelihood of peritoneal contamination. In fat ponies and donkeys – particularly those with underlying liver disease – treatment for hyperlipaemia with IV dextrose (and sometimes also insulin) may also be indicated.

A subset of gastric impactions seen in Europe and the UK seem to develop over a long period of time, with progressive thickening and fibrosis of the muscular layer of gastric wall. The cause of this syndrome is unknown, and it is typically only identified once the stomach has become massively enlarged or ruptured.

Failure of a standard feed impaction to respond to treatment with carbonated drinks and water, or immediate re-impaction during re-feeding (in the absence of other intestinal lesions or liver disease), could be suggestive of this devastating syndrome.

Other clues include a long-standing history of poor performance, poor appetite, failure to thrive or increased recumbency. The author has managed a couple of horses suffering from recurrent gastric impactions on a modified diet of soaked complete feed pellets, but they have rarely, if ever, done well in the long term.

Diagnosing primary gastric impactions is difficult, as all other intestinal causes need to be ruled out. An enlarged feed-filled stomach that does not empty normally is suggestive of a gastric impaction. Gastroscopy can tell us whether feed material is in the stomach, and whether the stomach is emptying at a normal rate, but cannot definitively identify an impaction as normal horses on a hay diet have dry feed material filling the stomach.

Ultrasound is a useful tool to measure the size of the stomach, and to identify various non-gastric underlying causes. Serum biochemistry parameters can be used to diagnose liver disease – particularly aspartate aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, glutamate dehydrogenase and bile acids.

Gastric impactions secondary to intestinal disease resolve spontaneously after resolution of the primary disease and adequate rehydration of the horse and gastric contents. Gastric impactions associated with severe liver disease often have a grave prognosis when the liver disease is due to pyrollizidine alkaloid poisoning. The author has successfully treated gastric impactions alongside other causes of liver disease, where the liver disease has been amenable to treatment (for example, cholangiohepatitis and hepatic lipidosis).

Gastric rupture has been reported secondary to gastric impaction, perforation of ulcers and idiopathically (particularly in Thoroughbreds). The underlying cause for idiopathic rupture is unknown and no treatment options exist5.

Two distinct types of gastric ulceration are identified in horses – namely equine squamous gastric disease (ESGD) and equine glandular gastric disease (EGGD). Sykes et al6 thoroughly reviewed the disease syndromes and reported an expert consensus, which is freely available online. Up to 100% of racehorses, 93% of endurance horses, 58% of sport horses and 59% of pleasure horses will suffer from ESGD, while up to 57% of horses may suffer from EGGD6.

Clinical signs associated with EGUS are non-specific and at best inconsistent. Examples of include poor appetite, poor body condition, weight loss, poor coat, bruxism, behavioural changes, colic and poor performance.

Gastroscopy remains the only way to definitively diagnose EGUS, although studies show that the histological degree of ulceration (especially in the glandular stomach) can be underestimated7,8. This might explain why some horses appear to respond to treatment despite the apparent absence of visible lesions in the stomach. Assessment of the clinical significance of visible lesions should never be based on endoscopic findings alone, but should include use, history and clinical signs6.

Proteomics is the study of proteins that allows correlations to be drawn between the proteins produced within the body and the start or progression of a particular disease. These protein markers are then used for diagnostic purposes and as targets for drug discovery.

Tesena et al9,10 have identified 10 protein markers of ESGD and 14 protein markers of EGGD. Further study is required to develop these markers into new diagnostic modalities. They can be obtained by a simple blood test, and the hope is they will one day allow us to non-invasively evaluate horses for the presence and progression of gastric ulcers without the need for fasting or gastroscopy.

Both ESGD and EGGD are commonly treated with the proton pump inhibitor omeprazole, which is given either as a buffered paste (2mg/kg to 4mg/kg once a day by mouth), enteric coated granule (1mg/kg once a day by mouth) or IM injection (not a licensed formulation)11,12.

While almost 80% of squamous ulcers will heal within four weeks of omeprazole treatment, only 25% of glandular ulcers heal in that time. The addition of sucralfate (12mg/kg twice a day by mouth) to the treatment regimen increases the healing rate to 67.5%.

Varley et al13 showed that misoprostol (5mg/kg twice a day by mouth) on its own was superior for EGGD healing and improvement in clinical signs compared to omeprazole/sucralfate combination. Given that glandular ulcers can deteriorate despite omeprazole treatment, misoprostol monotherapy should be considered for horses that don’t also have squamous lesions.

In cases that fail to respond to therapy, or those that deteriorate in spite of treatment, further diagnostics looking for underlying causes and histopathology of lesions should be considered. Strategies to either increase or decrease (depending on the case) duration and magnitude of acid suppression, changing the omeprazole formulation, dose or frequency, changing the gastric microbiota or controlling gastric and intestinal inflammation can also be considered for these cases.

Many prebiotics and probiotics, vitamins, antacids and mucosal protectants are used by horse owners for treatment and prevention of gastric ulcers with variable or questionable effects. In managing gastric ulceration, the author recommends that her patients have continuous access to good-quality forage. High carbohydrate concentrate feeds are replaced with a combination of balancers, vegetable oil and high-fibre feeds, depending on the horse’s body condition and caloric needs14.

Routines are managed to minimise anxiety and exercise sessions kept to a maximum of 45 minutes15,16. A small amount of high-fibre feed (such as chaff) is given 30 minutes prior to exercise to ensure maintenance of splanchnic perfusion during exercise and to prevent acid splashing.

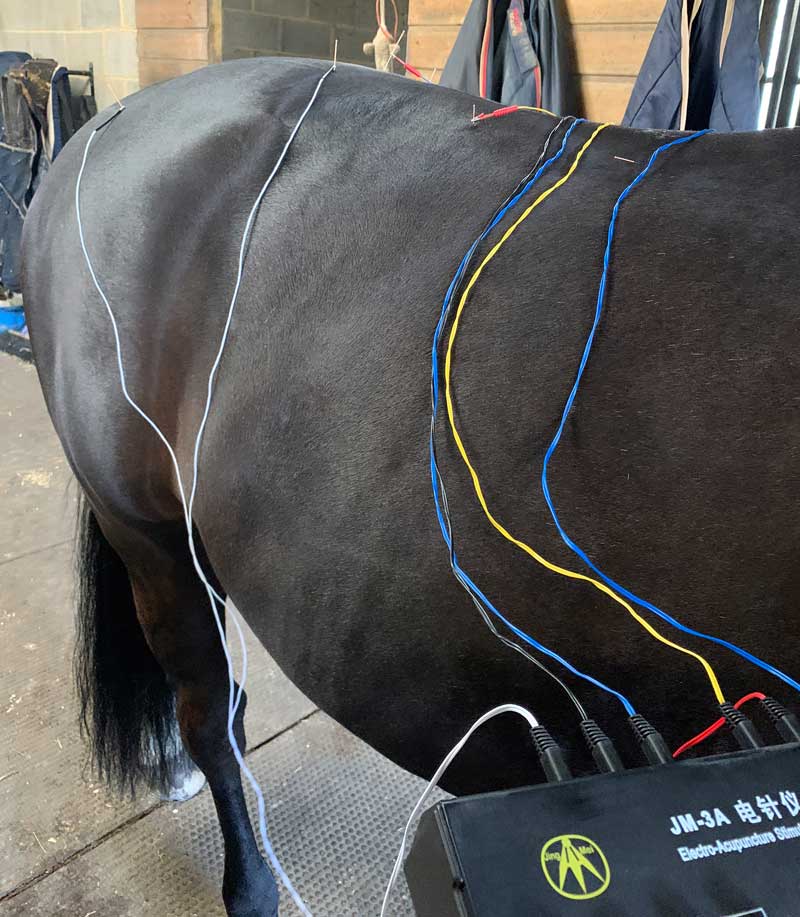

Omeprazole at 1mg/kg can be used to prevent gastric ulceration in horses in training17. In the author’s holistic practice, she sees many horses that were previously diagnosed with gastric ulcers, but whose clinical signs fail to respond to conventional Western medicines (with or without healing of ulcers) or that develop recurrent ulceration as soon as treatment is stopped. She has very good results with traditional Chinese veterinary medicine and acupuncture for resolution of clinical signs and prevention of ulcer recurrence.