26 Sept 2016

Figure 5. A small intestinal strangulation, demonstrating the multiple loops of distended small intestine, which may be palpable on rectal exam.

The first part of this two-part article reviewed the role of patient history and physical examination on decision making in horse colic and the use of diagnostic tests.

This part focuses on the two most commonly used diagnostic tests: abdominal palpation per rectum and nasogastric intubation. A survey of veterinary practitioners identified rectal examination was used in more than 75% of cases presenting with colic, and nasogastric intubation was used in more than 40% of cases1.

A large range of diagnostic tests exist for the investigation of horses presenting with colic, and the number and type of tests used by different practitioners varies significantly1,2.

Opinions vary as to whether every horse presenting with colic should have a rectal examination performed (where it is safe and practical), but it is the most commonly used and probably the most important diagnostic test.

The main factors restricting its use are the risk of injury (rectal tears) to the horse and risk of injury to the vet when performing the procedure, which may be particularly of concern in a field situation with limited restraint facilities. The incidence of rectal tears in horses undergoing rectal examination for colic is not known, but is considered to be very low. Factors thought to be associated with increased risk are young/unhandled animals, and animals that are difficult to handle – either as a result of temperament or their level of pain.

A judgement must be made on the size and age of the patient, and alternative techniques, such as ultrasonography and radiography, considered in small and/or young animals3. The client should be actively involved in decision making, have an understanding of the procedure being performed, the reasons for its use, its limitations and potential issues, and the importance of adequate restraint prior to rectal examination being performed.

Adequate restraint is essential in both the field and hospital environments. Physical restraint options include use of a twitch – lifting a foreleg, positioning the horse facing a solid wall (with sufficient space behind for the horse for safety during the examination), and bales of forage or bedding adjacent to and/or behind the horse. Horses should not be examined rectally over a stable door due to the risk of injury to the vet’s arm if the horse sinks down during the procedure.

Chemical restraint options include sedation with alpha-2 agonists, spasmolytics and analgesics. Acepromazine should not be used for sedation. The choice of alpha-2 agonist and the dosage used should be based on the required duration of action and any potential concerns over hypovolaemia. Doses of up to 0.5mg/kg of xylazine IV can be useful for short durations (15 to 30 minutes) to enable initial assessments and then re-evaluation of clinical signs. Detomidine or romifidine may be preferred if a longer duration of sedation is required for more prolonged procedures or transport of the patient.

The impact of chemical restraint on clinical parameters should always be considered. Alpha-2 agonists will cause a reduction in heart rate and respiratory rate, decreased gastrointestinal borborygmi and some visceral analgesia4,5. Where possible, this clinical data should be collected and assessed prior to drug administration.

Excellent descriptions of the examination technique and its interpretation exist in the literature6 and through online materials on commercial websites, such as www.boehringer-academy.co.uk

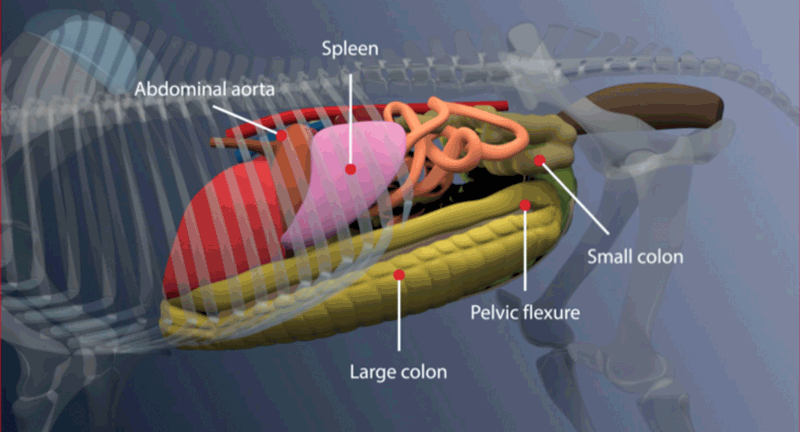

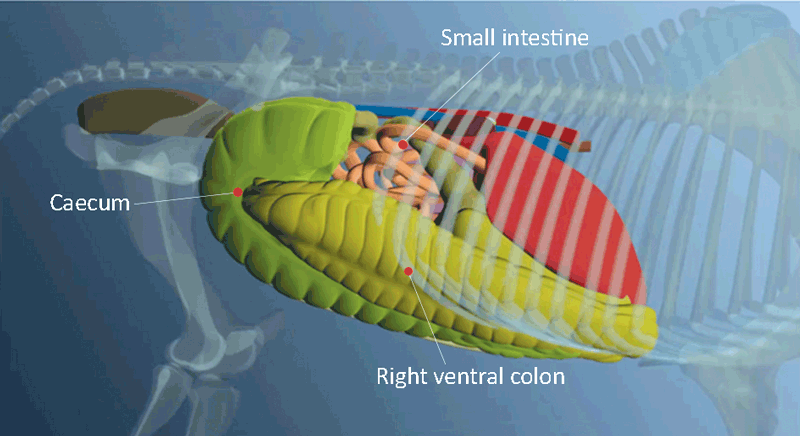

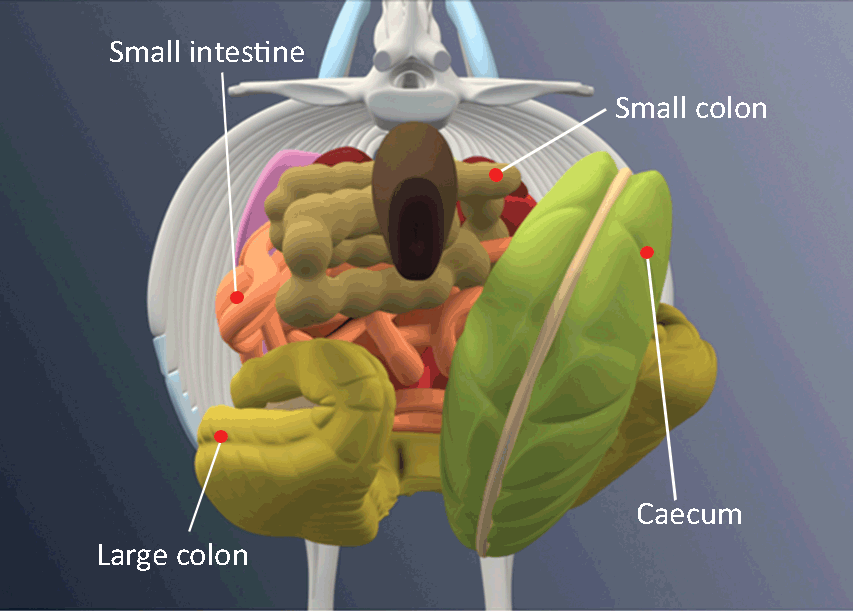

Interpretation of rectal examination findings should follow a similar approach to interpreting other diagnostic techniques, such as radiographs. This includes evaluating normal structures, describing the size, shape and nature of any abnormal findings, and then constructing a list of possible differentials. Normal anatomical features are described in Table 1 3,7 and shown in Figures 1 to 3.

| Table 1. Palpable anatomical features of main abdominal organs in the horse | |

|---|---|

| Structure | Anatomical features |

| Small intestine | • Small diameter (normal diameter lower than 5cm). • No taenial bands, no sacculations. • Normal contents are fluid, with or without some gas. • Normally located in the mid-abdomen (Figures 1 to 3). |

| Small colon* | • Small diameter. • Two taenial bands, sacculations present. • Normal contents are formed faecal balls. • Normally located in the mid-dorsal abdomen (Figure 3). |

| Caecum* | • Large diameter. • Four taenial bands, medial band palpable running from dorsal to ventral, sacculations present. • Contents vary, but are usually semi-solid. • Normally located in the right-dorsal abdomen (Figures 2 and 3). |

| Pelvic flexure* | • Medium to large diameter. • One taenial band (mesenteric band), no sacculations. • Normal contents are semi-solid/solid, but indentable on palpation. • Normally located in left-caudal abdomen, but may extend up to and over the midline in some normal horses on pasture (Figures 1 and 3). |

| Left-dorsal colon | • Large diameter. • Similar features to the pelvic flexure, with taenial bands and sacculations reappearing in the cranial abdomen. |

| Left and right-ventral colon | • Large diameter. • Four taenial bands, sacculations. • Normal contents are semi-solid/solid, but indentable on palpation. • Normally located on the ventral abdominal wall (Figure 2 and 3). |

| Right-dorsal colon | • Large diameter. • Three taenial bands, sacculations. • Normal contents are semi-solid/solid, but indentable on palpation. • Normally located in the right-dorsal abdomen, cranial and medial to the caecum. |

| Left kidney* | • Smooth, rounded caudal pole, palpable in most horses. • Located in the left-dorsal abdomen against the dorsal body wall. |

| Spleen* | • Solid soft tissue surface with no obvious protrusions or masses, pointed caudal border. • Located in the left-caudal abdomen against the left abdominal wall. |

| *Structures considered key normal landmarks on palpation. | |

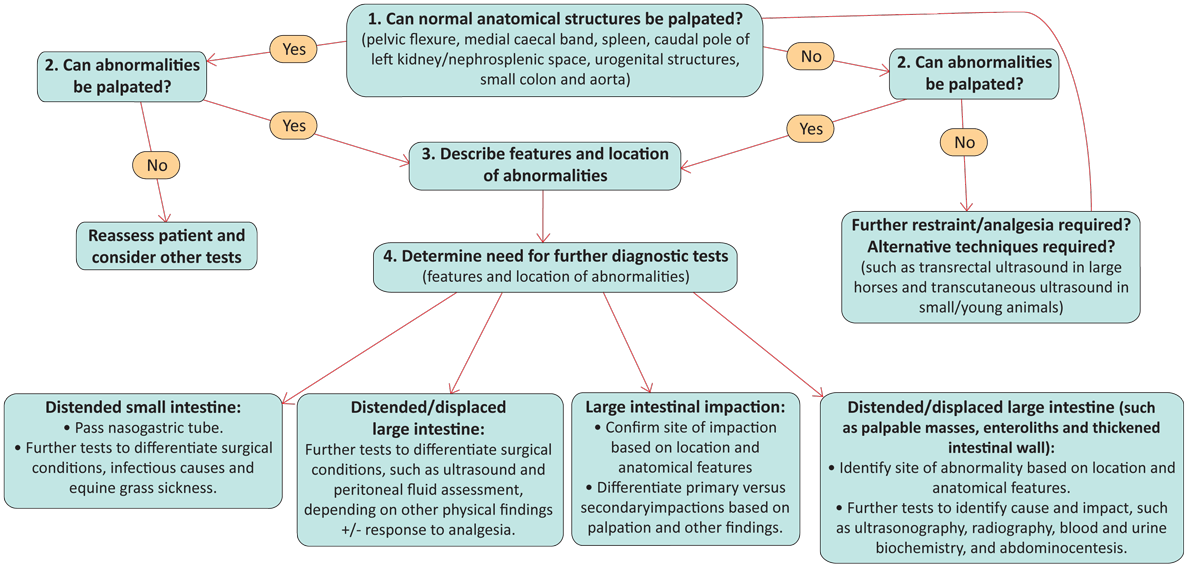

A decision-making process for evaluating rectal examination is described in Figure 4.

Transrectal or transcutaneous ultrasonography can be a useful technique to confirm or add further information on abnormal findings on rectal examination, providing information on aspects such as the degree of intestinal distension, the nature of intestinal contents, thickness of the intestinal wall and the intestinal motility8. It can also be a valuable aid to confirm rectal findings to enable less experienced practitioners develop their skill and confidence in recognising different abnormalities, and is more sensitive and specific than rectal examination in detecting abnormalities9.

The main aim of rectal examination should be for identifying aspects that will alter the diagnostic or therapeutic approach to a case, rather than focusing a definitive diagnosis. Examples are the presence of distended small intestine on rectal examination, indicating nasogastric intubation is required, or the presence of a large colon impaction, indicating the need for treatment with oral fluid therapy.

Definitive diagnoses often require additional diagnostic tests, and rectal findings may not be specific for a number of conditions. A common misinterpretation is the diagnosis of left dorsal displacement or nephrosplenic entrapment based on rectal palpation. The presence of large intestinal tympany in the left caudal abdominal region (either primary or secondary to other conditions, including displacement and impaction) can impede the ability to palpate the nephrosplenic space and lead to false-positive diagnoses of nephrosplenic entrapment.

A definitive diagnosis requires positive findings on transcutaneous ultrasonography10. The other main limitation of rectal examination is the region of the abdomen that can be palpated. This is dependent on the size of the horse, but, in general, palpation is limited to the caudal third of the abdomen, and a number of conditions affecting the cranial abdomen (such as gastric and sternal flexure impactions, and some epiploic foramen entrapment cases) may have no palpable abnormalities.

Other diagnostic tests, including transrectal and transcutaneous ultrasonography, gastroscopy, laparoscopy and exploratory laparotomy, may be required in some cases.

Despite these limitations, rectal palpation remains one of the key diagnostic tests for horses with colic. It is the only technique that can definitively diagnose common large intestinal impactions, and this diagnosis will trigger different treatment plans to other types of colic11,12. It is also essential to identify the location of impactions: pelvic flexure and caecal impactions have markedly different prognoses in terms of outcome and, therefore, client advice and treatment approaches need to be adjusted accordingly13,14.

Rectal palpation should not be reserved just for cases showing more severe signs of colic or cardiovascular compromise. Small intestinal distension on rectal examination can provide one of the earliest indicators of surgical obstructions (prior to the onset of systematic signs associated with cardiovascular compromise), and early recognition and treatment of these cases impacts on outcome and prognosis (Figure 5)15.

Nasogastric intubation is performed in horses with signs of colic, both for diagnostic purposes, but also for administering enteral fluids and treatments. Similar issues exist around restraint of the horse and risk to personnel involved. The potential complications, particularly epistaxis, can be distressing to the owner, and, once again, the owner should have an active involvement in decision making and an understanding of the reasons for performing this test and any potential complications.

The anatomicº configuration of the gastro-oesophageal junction in the horse means gastric rupture is a significant risk in horses with proximal obstructions (including small intestinal strangulations, grass sickness, ileal impaction and gastric impactions). Nasogastric intubation is, therefore, an essential procedure in these cases, and indications for nasogastric intubation are outlined in Table 2.

| Table 2. Indications for nasogastric intubation | |

|---|---|

| Clinical signs indicating need for nasogastric intubation | Diagnostic test results indicating need for nasogastric intubation |

| • Severe/continuous signs of pain. • Elevated heart rate (more than 60bpm in adult horses). • Spontaneous reflux. |

• Distended loops of small intestine on rectal examination. • Distended loops of small intestine on ultrasound examination. • Evidence of hypovolaemia and/or electrolyte disturbance. |

| Nasogastric intubation should be performed in every case with clinical signs/history/suspicion of proximal intestinal obstruction. | |

Presence of more than one or two litres of fluid in an adult horse should be considered abnormal and consistent with a proximal obstruction. Impaction of the stomach with solid material may also be identified by encountering a solid obstruction to passage of the stomach tube beyond the gastro-oesophageal junction.

Dealing with colic in horses can be an extremely emotive and distressing experience for owners. They can feel panicked into making decisions, which, on later reflection, they may regret.

Negative experiences from one horse can have a major impact on future decision making, such as assuming any future episodes will be critical, or that surgical cases always have an unsuccessful outcome. This may affect their willingness to have further investigations done on a horse presenting with colic, and may limit options for successful outcomes for future cases.

One study showed a decline in the number of horses undergoing surgical treatment for colic over a 10-year period16. In another study of horse owners’ knowledge and opinions of colic, many had a poor understanding of what colic is, what causes it and the different treatment options17. Participants in the survey wanted to make informed decisions and were keen for further information17,18.

Fact sheets, consent forms and educational materials can be helpful for owners, both during and after a colic episode, to understand the different processes, procedures, and their limitations.

A new initiative is establishing a series of educational materials for horse owners, including information on commonly performed diagnostic procedures. These will be freely available through the British Horse Society website for horse owners, but also for veterinary practitioners to download and use to support their client communications if they wish.

Ensuring the owner has an active, informed involvement in decision making is essential to improve the recognition, management and prevention of colic, and ensure the best options for each case can be considered fully.